Quote Analysis

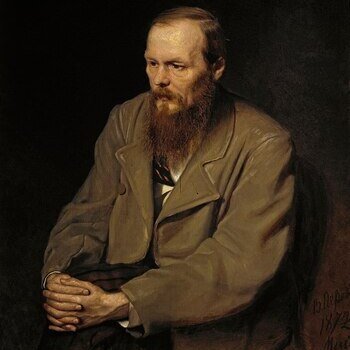

We live in a world that often rushes to judgment. Social media thrives on outrage, and moral certainty is worn like a badge of honor. But what if true wisdom lies not in condemnation, but in comprehension? Fyodor Dostoevsky challenges us to pause and reflect with his timeless words:

“Nothing is easier than to denounce the evildoer; nothing is more difficult than to understand him.”

This quote captures the essence of Dostoevsky’s philosophical and literary worldview — a worldview in which morality is never black and white, and where understanding human behavior requires empathy, depth, and patience. So what exactly did he mean, and why does it still matter today?

Introduction to Dostoevsky’s Moral Philosophy

Fyodor Dostoevsky was not just a novelist — he was a thinker deeply concerned with the complexities of the human soul. His stories go far beyond good-versus-evil plots; they explore how people struggle with guilt, redemption, doubt, and meaning. Dostoevsky didn’t paint characters as simply villains or heroes. Instead, he presented people as morally conflicted, often torn between darkness and light.

This quote — “Nothing is easier than to denounce the evildoer; nothing is more difficult than to understand him” — is a perfect window into Dostoevsky’s ethical world. He believed that judging someone for their wrongdoing is easy because it requires no effort or self-reflection. But trying to understand why someone committed a harmful act — that takes empathy, patience, and courage. For Dostoevsky, this understanding is essential if we want to grow as individuals and as a society. His novels teach us that true morality lies not in labeling others as evil, but in recognizing the inner battles that led them there.

The Illusion of Moral Superiority

When we judge others quickly, we often feel a sense of righteousness — as if we are on the “good” side. This feeling can be comforting, but it’s also deceptive. It allows us to feel superior without ever asking hard questions. Dostoevsky saw this behavior as shallow. Simply calling someone “bad” may make us feel better, but it doesn’t bring us any closer to truth or justice.

Judging others harshly is easy for a few key reasons:

- It protects us from looking at our own flaws.

- It helps us avoid the discomfort of moral complexity.

- It satisfies our desire for clear-cut answers.

But these are illusions. In real life, people don’t fit into neat categories. Many who commit wrongdoings have suffered themselves. Some act out of fear, desperation, or misunderstanding. Others are shaped by trauma, social pressure, or mental illness.

Dostoevsky’s message is simple: condemning someone requires almost no thought. But truly seeing another person — even someone who has done wrong — demands humility. It means we have to admit that we don’t always know the whole story.

The Challenge of Understanding the “Evildoer”

Understanding someone who has done harm is not the same as excusing their actions. This is an important distinction that Dostoevsky wants us to grasp. He does not suggest that we let people off the hook or ignore justice. Instead, he is asking us to look deeper — to see the full human being behind the act.

Why is this so difficult? Because understanding requires us to:

- Ask uncomfortable questions

- Listen instead of reacting

- Imagine what it’s like to be in someone else’s shoes

- Confront the idea that we, too, are capable of doing harm

This is not a passive process — it’s active, demanding, and emotionally challenging. In novels like Crime and Punishment, Dostoevsky shows us characters who commit terrible acts but are not monsters. They are human beings — full of contradictions, regrets, and desires. When we try to understand such people, we become more aware of the forces that shape all human behavior, including our own.

Dostoevsky and the Moral Complexity of Good and Evil

In most stories we read or watch, characters are split into good guys and bad guys. This makes the plot simple and easy to follow. But life isn’t like that — and Dostoevsky knew it. His work challenges us to think beyond simple labels like “evil” or “hero.” Instead, he shows us that good and evil often exist within the same person.

His characters are often caught in deep inner conflict. For example, someone may commit a terrible act but also show moments of love, guilt, or sacrifice. Another may appear noble on the outside but hide selfish or cruel thoughts. Dostoevsky’s message is this: people are complicated. No one is completely good, and no one is completely bad.

This moral complexity doesn’t mean we should accept all behavior as okay. Rather, it teaches us that we must try to see the full picture. When we recognize that human nature is made up of contradictions, we stop rushing to judge and start asking deeper questions. And that’s where real moral growth begins.

Why This Message Matters in Today’s World

Dostoevsky’s quote is not just a 19th-century idea — it speaks directly to today’s culture. We live in a time where judgments are made quickly, especially online. A single post or mistake can lead to public shaming, and people are often reduced to a single action or opinion. This is called “cancel culture,” and while it may come from a desire for justice, it often ignores the complexity of human behavior.

Understanding someone doesn’t mean you agree with them. But it does mean you try to learn:

- What shaped their actions

- What pressures or fears they were under

- What pain or confusion they might have been dealing with

If we only focus on condemning people, we miss the chance to help them change. Worse, we miss the chance to grow ourselves. When we stop listening and just point fingers, we close the door to real dialogue, healing, and learning.

Dostoevsky challenges us to resist this tendency. He calls on us to slow down, think more deeply, and ask harder questions. In doing so, we can become not just more just — but more human.

The Deeper Lesson: Compassion Is a Moral Strength

Let’s return to the core of the quote: “Nothing is easier than to denounce the evildoer; nothing is more difficult than to understand him.” This is more than just an observation — it is a moral challenge.

Dostoevsky is teaching us that true compassion is not soft or naïve. It takes strength. It takes effort. And it takes the courage to look at someone who has failed — and still see them as a person.

This approach doesn’t remove accountability. People must still face the consequences of their actions. But by choosing to understand, we add something powerful to the moral conversation:

- We promote empathy instead of hatred

- We open space for redemption

- We encourage reflection instead of revenge

In the end, Dostoevsky’s quote reminds us that understanding is not weakness — it is the highest form of wisdom. Anyone can point a finger. Few are willing to look deeper. And those who do, help create a more thoughtful, more compassionate world.

You might be interested in…

- Why “Pain and Suffering Are Always Inevitable for a Large Intelligence and a Deep Heart” Still Resonates Today

- Why “The Mystery of Human Existence Lies Not in Just Staying Alive” Is Dostoevsky’s Deepest Insight About Meaning

- Why “Man is Sometimes Extraordinarily, Passionately, in Love with Suffering” Still Resonates – Dostoevsky’s Psychological Depth

- What Dostoevsky Meant by “Nothing is easier than to denounce the evildoer; nothing is more difficult than to understand him”

- Why ‘To Go Wrong in One’s Own Way Is Better Than to Go Right in Someone Else’s’ Captures Dostoevsky’s Philosophy of Freedom