Quote Analysis

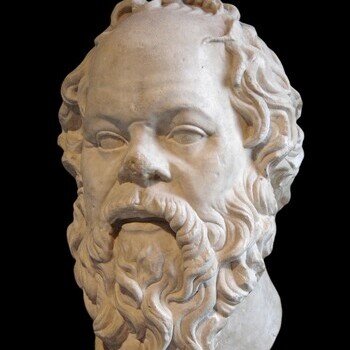

Most people don’t wake up one day and choose a “shallow” life. It usually happens quietly—through routines, borrowed goals, and habits you never stop to question. That’s why Socrates’ famous line still cuts through the noise. When he said:

“The unexamined life is not worth living,”

He wasn’t praising constant overthinking. He was warning about something more ordinary and more dangerous: living on autopilot. So what does this quote actually demand from us—and how can it shape the way we make decisions, build character, and take responsibility for who we become?

What Socrates Really Meant by “the Unexamined Life”

When Socrates says “The unexamined life is not worth living,” he is not claiming that a life without constant analysis has zero value. He is pointing to a different idea: a life that is never questioned can easily become a life you didn’t truly choose. In simple terms, “unexamined” means you move through days guided by habit, social pressure, fear of judgment, or comfort—without checking whether your motives and values are actually yours.

Think of it like this: if you never look at your inner “map,” you may still walk a long distance, but you might end up in the wrong place. Socrates is teaching that a human being has a special responsibility: to notice what is happening inside—why we want what we want, why we avoid what we avoid, and what we call “normal” without evidence.

Historically, this fits the Greek idea that virtue and character are not accidents—they are built through awareness and practice. Socrates questioned people publicly because he believed ignorance often hides behind confidence. On a personal level, his message is straightforward: if you don’t examine your beliefs, you can sincerely defend unfairness, cruelty, or selfishness—simply because you never tested your assumptions.

A good way to understand his meaning is to translate it into everyday language:

- You don’t need to question everything every minute.

- But you do need to question the things that steer your life: your priorities, your habits, your moral choices.

- Otherwise, you may live efficiently—but not wisely.

Self-Examination vs. Overthinking

Many people hear this quote and imagine endless self-analysis that leads to anxiety. That is not what Socrates is recommending. Overthinking usually feels like spinning in circles: you replay situations, worry about outcomes, and get stuck in “what if” scenarios. Socratic self-examination is different. It aims for clarity, not mental noise. It is more like cleaning a window so you can see what is true.

To make the difference clear, look at the goal:

- Overthinking asks: “What if everything goes wrong?”

- Self-examination asks: “What is the right thing to do—and why?”

Socrates cared about reasoning that leads to better choices. He would say: if your thinking does not improve your honesty, fairness, and responsibility, then it is not the kind of thinking he is praising. In fact, he often challenged people who used clever words to avoid moral accountability.

Modern life makes this distinction even more important. Social media, constant comparison, and productivity culture can create a “busy mind” without a “clear mind.” You can spend hours consuming opinions and still never ask what you truly believe. Socratic self-examination is like a checkpoint: you pause and verify direction.

Here is a practical teacher-like rule: good self-examination produces a next step. It ends with action or correction, not with endless doubt. For example, instead of replaying an argument all night, you ask: “Was I fair? Did I listen? What should I apologize for? What boundary should I set?” That turns reflection into character-building.

The Questions That Break Autopilot Thinking

Socrates’ method becomes powerful when you translate it into simple questions that expose your hidden motivations. Autopilot thinking is not always dramatic; it often looks “normal.” You keep doing what you’ve always done, saying what your group expects, chasing goals you never chose consciously. Self-examination interrupts that automatic pattern.

Socratic questions are usually short, but they hit deeply because they remove excuses. Here are examples that work in everyday life, with a clear purpose behind each:

- “Why am I doing this?”

This separates choice from habit. It reveals whether you are acting from fear, approval-seeking, or genuine values. - “Is this fair?”

This tests your moral consistency. It forces you to consider whether you would accept the same behavior if you were on the receiving end. - “What am I avoiding?”

Avoidance often hides the truth. People avoid uncomfortable conversations, responsibility, or the risk of failure—and then call it “being realistic.” - “What kind of person does this decision train me to become?”

This is one of the most Socratic questions. It reminds you that repeated choices form character, even when the choice seems small. - “If I continue this for a year, what will it cost me?”

The cost may not be money; it may be dignity, peace of mind, self-respect, or trust in relationships.

To connect this to modern life, imagine someone chasing a career only for status. From the outside it looks successful. But Socratic examination asks: “Whose definition of success am I living?” That one question can change a life path. This is why Socrates links “examination” with a life worth living: it protects you from living someone else’s script.

Truth About Yourself as the Foundation of a Stable Character

Socrates treats self-knowledge as more than “nice to have.” For him, it is the base layer of a solid character—like a building needs a strong foundation before you decorate it. If you do not tell yourself the truth, your decisions may look confident on the outside but remain shaky on the inside, because they are guided by excuses, image, or denial.

Historically, this fits Socrates’ broader mission in Athens: he challenged people who sounded wise but could not explain their beliefs clearly. Why? Because unclear beliefs produce unstable behavior. A person may talk about justice yet act unfairly when it benefits them. That mismatch often comes from a blind spot: the person has never examined the motives behind their “principles.”

In modern life, self-deception is common because it is comfortable. For example, someone might say, “I’m just honest,” but what they practice is harshness without empathy. Another might say, “I’m loyal,” but what they practice is fear of being alone. Socratic examination asks you to separate the label from the reality.

A teacher-like way to put it is this: character becomes stable when your inner story matches your outer behavior. That does not mean you never fail; it means you can name your failure accurately and correct it. Without self-truth, you keep repeating the same patterns while blaming circumstances. With self-truth, you gain a quiet strength: you know what you stand for, where you are weak, and what you must practice to become better.

Not Just Surviving, but Understanding How You Live

Socrates is not impressed by mere survival. People can “get through life” while never asking whether their way of living is worthy of a human being. Here “worthy” does not mean famous or rich; it means lived with awareness, responsibility, and moral direction. A person can be busy, productive, and socially respected—and still live in a way that feels hollow, because the life is driven by momentum rather than meaning.

Historically, Greek philosophy cared about how to live well (not just how to live long). Socrates pushes the idea that life is shaped by choices, and choices require reasons. If you cannot explain your reasons, you are vulnerable to manipulation: trends, group pressure, fear of missing out, and the need for approval can steer you.

In modern terms, consider someone who always says yes at work, answers messages instantly, and never rests. From the outside it looks responsible. But Socratic reflection asks: “Is this discipline—or is it fear of being disliked?” Another example: someone keeps buying things for comfort. The question becomes: “Is this pleasure—or avoidance of emptiness?”

The philosophical point is simple: a human life is not only a sequence of events; it is a pattern of decisions. When you understand that pattern, you can change it. When you don’t, you repeat it. Socrates is arguing that worth is connected to this ability to notice, judge, and choose—not perfectly, but consciously.

How to Apply Socrates’ Message Today: A Simple Practice of Self-Examination

A quote becomes useful only when it becomes a habit, not just a sentence. Socrates would likely say: if self-examination is real, it should be regular, concrete, and honest—not dramatic. You do not need long journaling sessions or complicated techniques. You need short moments where you stop and check your direction.

Here is a practical structure that fits modern life and avoids overthinking. You can treat it like a “mental hygiene” routine:

- Daily (2–3 minutes):

Ask: “What did I do today that I respect?” and “What did I do today that I need to correct?”

This keeps your conscience awake without turning life into a courtroom. - Weekly (10 minutes):

Ask: “Which habit is shaping me the most right now?”

Example: scrolling, procrastination, people-pleasing, avoidance of difficult talks. Then ask: “What need is this habit serving?” - Before a big decision:

Ask: “If everyone knew my real motive, would I still be proud of this choice?”

This question often separates integrity from image-management. - After conflict:

Ask: “What part of me was threatened—pride, control, fear, insecurity?”

This helps you learn from emotional reactions instead of repeating them.

The deeper lesson is philosophical: self-examination is how you become the author of your life rather than a passenger. It will sometimes feel uncomfortable because it removes easy excuses. But that discomfort is not a problem—it is often the sign that you are finally seeing clearly.

You might be interested in…

- The Meaning Behind “The Unexamined Life Is Not Worth Living” — What Socrates Really Meant

- Why Socrates Said “So One Must Never Do Wrong” — The Hardest Test of Moral Consistency

- What Socrates Meant by “Not Life, but a Good Life, Is to Be Chiefly Valued” — Why Integrity Matters More Than Survival

- The Meaning Behind “If it were necessary either to do wrong or to suffer it…” — Why Socrates Chose Suffering Over Injustice

- The Meaning Behind “I neither know nor think that I know” — Socrates on Intellectual Humility