Quote Analysis

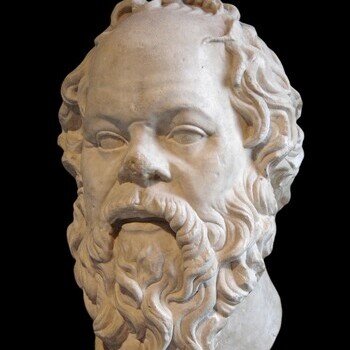

Most people have opinions about everything—politics, relationships, success, morality—often with total confidence. But how often do we stop and ask whether that confidence is earned? That’s exactly where Socrates quietly challenges us. In one short line, he draws a sharp boundary between honest thinking and pretend certainty:

“I neither know nor think that I know.”

This isn’t a claim of ignorance for show. It’s a disciplined refusal to act like you understand something when you don’t—and it’s the starting point of real learning, better judgment, and clearer conversations.

Meaning of the quote in one clear idea

Socrates is not saying, “I know nothing” as a dramatic slogan. He is saying something more careful and more useful: I do not claim knowledge unless I can justify it. The key is the second part—“nor think that I know.” That is a warning about a very common mental mistake: we often feel certain, so we assume we know. Socrates separates those two things.

Think of it like this: you might have a strong opinion about a person (“He is selfish”), a situation (“This will fail”), or a big topic (“Money makes people unhappy”). But if someone asks, “What exactly are you basing that on?” many people get annoyed—because the confidence was never supported by real reasons. Socrates is teaching the opposite habit: if you cannot explain your reasons, you should lower your certainty.

Historically, this fits Socrates’ method in Athens, where he questioned respected citizens—politicians, poets, craftsmen—and showed that many were confident but unclear. The point was not to humiliate them; it was to show that clear thinking begins when you admit the limits of what you can prove. In modern life, the same lesson applies whenever you face complex issues: if you don’t truly know, don’t pretend—ask, test, and learn.

“I don’t know” vs. “I think I know” — the crucial difference

This quote becomes powerful once you see how it attacks false certainty, not ignorance. Saying “I don’t know” is honest, but many people avoid it because it feels like weakness. Socrates shows that the real weakness is the opposite: acting like you know when you don’t. That is what creates bad decisions, pointless arguments, and stubbornness.

Here’s a simple classroom-style distinction:

- Not knowing means: “I lack information or proof.”

- Thinking you know means: “I’m treating my belief as if it were a fact.”

- Knowing (in the Socratic sense) means: “I can explain the reasons, defend them, and revise them if better evidence appears.”

A modern example: someone reads one headline and immediately says, “This proves the whole system is corrupt.” That may be a suspicion, but it is not knowledge. Another example: in relationships, a person says, “I know you don’t care,” when the truth is, “I feel insecure and I’m guessing your intentions.” Socrates would push you to separate what you feel from what you can justify.

This difference matters because “thinking you know” makes you closed. You stop listening, you stop checking, and you start defending an identity (“I’m right”) instead of searching for truth. Socrates teaches a better habit: confidence should be proportional to evidence. When evidence is weak, humility is not a weakness—it is accuracy.

Intellectual humility as a method (not a personality trait)

People often misunderstand humility as being quiet, shy, or “not having opinions.” Socratic humility is not that. It is a method of thinking—a disciplined way to handle uncertainty. Socrates can be very direct and even provocative, but he stays honest about what he can truly claim. That is the teacher’s lesson here: humility is not about lowering yourself; it’s about raising your standards for what counts as knowledge.

In practice, this method looks like a repeated cycle:

- State a claim clearly (not vaguely).

- Ask what would make it true (reasons, evidence, definitions).

- Test the claim (examples, counterexamples, consequences).

- Adjust your conclusion (strengthen, weaken, or change it).

Historically, this is why Socrates is connected to the “Socratic method.” He didn’t give long lectures; he asked targeted questions that exposed confusion. When someone said, “Justice is X,” he would ask, “Does that fit this case? What about that case?” The goal was to move from slogans to understanding.

Today, this method is incredibly practical. At work, it prevents confident nonsense: instead of “This plan will definitely succeed,” you ask, “What assumptions must be true?” In everyday life, it reduces conflict: instead of “I’m sure you meant to insult me,” you ask, “What evidence do I have, and what else could explain it?” Philosophically, it is a cure for ego because it trains you to value truth over pride. You don’t lose face by admitting uncertainty—you gain clarity by refusing to fake certainty.

Ego as the main obstacle to learning

If you want to understand why Socrates’ sentence is still relevant, look at the role of ego. Ego is the part of us that wants to look competent, win arguments, and avoid embarrassment. That sounds harmless, but in thinking it becomes a serious problem—because ego often prefers being right over finding what is true. Socrates targets exactly that weakness. When he says he does not “think that he knows,” he is refusing the ego’s favorite shortcut: confident talk without solid ground.

In ancient Athens, public reputation mattered. If a respected citizen admitted “I’m not sure,” it could look like weakness. Socrates pushed against that culture by showing a simple idea: pretending to know does not make you wise—it makes you fragile. The moment someone questions you, you become defensive, not curious. That is ego in action.

A modern example is social media, where people post strong opinions within seconds. The more confident the tone, the more attention it gets. But attention is not the same as truth. Another example is in relationships: someone says, “I know you did this on purpose,” when the real cause is fear or insecurity. Ego wants control, so it invents certainty. Socrates offers a cleaner habit:

- Notice when you need to be right.

- Separate that need from the actual evidence.

- Choose honesty over performance.

Philosophically, this is a cure: ego narrows the mind, while admitted limits keep the mind open.

Facts, assumptions, and opinions: how to separate them

Socrates’ quote becomes practical when you use it as a sorting tool. Many disagreements happen because people mix three different things and treat them as equal: facts, assumptions, and opinions. A teacher would put it simply: if you don’t label your claim correctly, you will think you know when you don’t. Socrates is careful because he refuses to confuse categories.

Here is a clear way to separate them:

- Fact: something you can check or reasonably verify.

Example: “The meeting starts at 10:00.” You can look at the schedule. - Assumption: something that might be true, but you haven’t confirmed it.

Example: “He didn’t reply because he’s angry.” That is a guess, not proof. - Opinion: a value judgment or preference.

Example: “This plan is better.” That may be reasonable, but it needs criteria.

Historically, Socrates questioned definitions because people often used big words—justice, courage, wisdom—without clear meaning. He was not obsessed with definitions for fun; he knew that unclear words produce false certainty. If you can’t define what you’re talking about, you can’t truly know it.

In modern life, this separation protects you from mistakes. In business, teams fail when assumptions are treated as facts (“Customers will love it”). In personal life, conflicts grow when assumptions are treated as mind-reading (“I know what you meant”). The Socratic approach is to speak more accurately: “I suspect,” “I’m not sure,” “I need evidence.” That is not weakness; that is disciplined thinking.

Practical applications: conversation, work, and relationships

Socrates is not only for philosophy classrooms. His sentence works like a daily tool because it changes how you speak and how you decide. When you stop pretending to know, you start asking better questions—and better questions lead to better outcomes.

In conversations, the Socratic habit reduces pointless fights. Many arguments are actually two egos colliding, not two minds searching for truth. Instead of “You’re wrong,” you learn to say, “What makes you think that?” or “What would count as proof?” That small shift turns a battle into an investigation.

At work, this quote prevents costly overconfidence. Good professionals do not avoid uncertainty; they manage it. Socratic thinking looks like this:

- Identify what you truly know (data, tested results).

- Identify what you believe but haven’t tested (assumptions).

- Decide what to test next (small experiments, feedback, benchmarks).

In relationships, it is especially powerful because people often confuse feelings with facts. “I feel ignored” is real as an emotion, but it does not automatically mean “You ignore me on purpose.” Socrates would teach you to slow down: describe what happened, explain how you felt, and ask for the other person’s perspective. That creates clarity instead of accusation.

The philosophical dimension here is simple: real wisdom is not having an answer for everything; it is knowing when your certainty is earned and when it is only a mask. Socrates’ sentence trains you to choose accuracy, honesty, and learning—over quick conclusions and pride.

You might be interested in…

- What Socrates Meant by “Not Life, but a Good Life, Is to Be Chiefly Valued” — Why Integrity Matters More Than Survival

- The Meaning Behind “If it were necessary either to do wrong or to suffer it…” — Why Socrates Chose Suffering Over Injustice

- The Meaning Behind “The Unexamined Life Is Not Worth Living” — What Socrates Really Meant

- Why Socrates Said “So One Must Never Do Wrong” — The Hardest Test of Moral Consistency

- The Meaning Behind “I neither know nor think that I know” — Socrates on Intellectual Humility