Quote Analysis

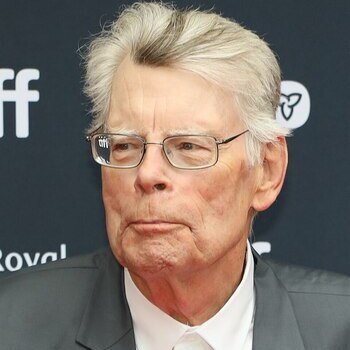

Horror stories don’t just entertain us—they quietly teach us how to sit with fear without being consumed by it. When real life feels uncertain, our minds often look for a safer way to face anxiety, loss, and the unknown. That’s why Stephen King’s insight still lands with such precision:

“The answer seems to be that we make up horrors to help us cope with the real ones.”

In a controlled setting—on a page or a screen—fear becomes something we can observe, name, and even pause. But why does turning terror into fiction make reality feel more manageable?

Core Meaning of the Quote

Stephen King is saying that fictional horror has a real psychological function. We do not invent monsters and nightmares only for entertainment; we use them as a tool to manage the fears that already exist in everyday life. Real-life horrors—illness, violence, loss, instability—often feel chaotic and unfair. They arrive without warning and do not follow a clear storyline. Horror fiction, however, takes the raw feeling of fear and gives it a shape. It turns anxiety into something you can point to: a haunted house, a creature, a curse, a stalker, an apocalypse. That “shape” matters because the mind handles defined threats better than vague dread.

Think of the difference between being anxious for no clear reason and being afraid of something specific, like a storm you can track on a radar. In both cases you feel tension, but in the second case your brain can organize the emotion: “This is what I’m reacting to.” King’s point is that horror stories do something similar. They translate a blurry inner panic into a concrete narrative, and that narrative makes fear feel more manageable—because it becomes understandable, discussable, and containable.

Why Horror Feels “Safe” Even When It Scares You

The key idea here is controlled fear. When you read a horror novel or watch a scary film, your body reacts as if something threatening is happening—your heart rate rises, your muscles tense, you become alert. But part of your mind knows you are safe. That combination creates a special training environment: you experience strong emotion without real-world danger. It is like using a flight simulator instead of crashing a plane to learn how to respond.

This safety is not trivial; it changes what fear does to you. In real life, fear can trap you because you cannot pause reality. In fiction, you can.

- You can stop at any moment (close the book, pause the movie).

- You can choose the intensity (mild suspense vs. extreme horror).

- You can process it afterward (talk about it, rewatch it, analyze it).

Because you have control, the fear becomes something you practice handling rather than something that handles you. Historically, people have always created “safe containers” for frightening ideas—myths, ghost stories, cautionary tales—often told around fires or in communities. Modern horror is the same human habit, just with new media: we rehearse danger inside a protected space.

Horror as Emotional Training for the Unknown

If you want a teacher-like way to understand King’s claim, think of horror as a lesson in emotional endurance. Many fears in life are not about a specific object; they are about uncertainty—what might happen, what you cannot control, what you cannot predict. Horror places you inside that exact feeling on purpose: you don’t know what is behind the door, you don’t know who can be trusted, you don’t know if the character will survive. Your brain learns to stay present while discomfort builds.

This is why horror can feel strangely satisfying after it ends. You went through tension, you tolerated it, and you came out intact. That creates a sense of competence: “I can handle intense emotions.” In modern life, where stress often has no clear endpoint (financial pressure, social instability, health worries), that experience can be valuable.

Philosophically, horror also teaches a truth about being human: we do not fully control our world. A good horror story does not pretend life is neat. It shows vulnerability—sometimes through supernatural symbols, sometimes through human cruelty—then forces you to face it. The training is not “be fearless.” The training is “feel fear, and keep going.”

Turning Vague Anxiety Into Something You Can Name

One of the strongest parts of King’s idea is that horror gives fear a vocabulary. When anxiety is vague, it feels endless. You sense something is wrong, but you cannot explain it clearly, so your mind keeps scanning for threats. Horror stories reduce that chaos by transforming abstract dread into a concrete image and a clear conflict. In other words, horror “names” what scares you.

For example, a zombie apocalypse can represent social collapse and helplessness. A haunted house can represent unresolved grief, trauma, or a past you cannot escape. A ruthless monster can represent illness, addiction, or violence—forces that do not negotiate. Once fear is expressed as a story, you can think about it rather than just suffer it.

This is also why people often return to horror during difficult periods. When the world feels unstable, a genre that directly deals with danger can feel oddly clarifying: it matches the emotional weather outside. The discomfort becomes legible—like turning static noise into a song with a rhythm. You may still feel uneasy, but now the unease has edges, meaning, and limits. That is what makes it easier to carry.

Story Structure as Order in Chaos

One reason horror helps us cope is that fiction imposes structure on experiences that feel shapeless in real life. In reality, suffering often arrives without a clear beginning, and it may not provide a satisfying ending. Horror stories, however, usually follow a pattern: something feels “off,” the threat reveals itself, tension escalates, and then there is a climax and an outcome. That arc matters because the human mind learns through patterns. When fear is placed inside a story, it becomes something the mind can track rather than something that simply overwhelms.

Historically, this is not new. Folklore and myth often served the same purpose. Communities told ghost stories and legends not because they were naïve, but because narrative helped them explain danger—disease, wild animals, death, betrayal—in forms people could remember and share. Today we do the same through novels, films, and games. A pandemic may feel like endless uncertainty, but a horror narrative turns uncertainty into a sequence: warning signs, threat recognition, survival decisions, and consequences. Even if the story ends badly, it still offers one thing life sometimes withholds: a completed shape. That “shape” can bring relief because it reduces mental chaos.

The Philosophical Layer: Meaning-Making When Life Feels Random

Under King’s sentence sits a deeper philosophical claim: people are meaning-making creatures. When life feels random or unfair, we instinctively search for interpretations that help us endure it. Horror is one of the most honest genres in this respect, because it does not pretend the world is always safe or morally balanced. Instead, it asks a difficult question: “What do you do when the universe does not protect you?”

This is why horror can feel strangely “true,” even when it is supernatural. It dramatizes themes that philosophy has wrestled with for centuries: vulnerability, mortality, the limits of control, and the tension between order and chaos. In a haunted-house story, for instance, the ghost may represent unfinished business, guilt, or the persistence of the past. In a creature feature, the monster may symbolize nature’s indifference or the fear that civilization is a thin surface over something primal.

A teacherly way to summarize it is this: horror gives you a rehearsal space for existential questions. It does not answer them with lectures; it answers them with situations. You watch characters face the unknown, and you quietly test your own beliefs: “What would I do? What matters when safety disappears? What do I rely on?”

Why Horror Becomes Popular in Difficult Times

If you look at cultural history, you will notice a pattern: when societies go through stress—economic collapse, war anxiety, political tension, pandemics—dark genres often surge. That is not because people suddenly become “more morbid.” It is because horror matches the emotional climate. When daily life already contains uncertainty, stories that name fear directly can feel less exhausting than cheerful content that denies it.

In modern terms, horror can function like emotional alignment. If you feel uneasy but cannot explain why, a horror story offers an external script that mirrors the internal mood. That mirroring can be soothing, because it tells you: “This feeling has a form. It is recognizable. You are not alone in it.” It also creates a sense of community—people watch, discuss, and interpret these stories together, which turns private anxiety into shared language.

There is another reason: horror often restores agency. In real crises, individuals may feel powerless. In fiction, even when characters are terrified, they still make choices—hide, run, fight, sacrifice, protect someone. Those decisions remind the audience that action is possible even under pressure. That lesson can be subtle but important: fear does not remove responsibility; it clarifies priorities. And sometimes, the first lesson is simply beginning – “The scariest moment is always just before you start”—because avoidance keeps fear vague, while action turns it into something you can handle step by step.

A Balanced View: When Horror Helps and When It Doesn’t

It is important to keep the analysis realistic: horror does not help everyone in the same way. For some people, especially those already overwhelmed by stress or trauma, intense horror can amplify fear rather than contain it. The difference often depends on the person’s current emotional “load,” and on the type of horror they choose.

Here is a useful way to explain it:

- Helpful horror tends to create tension but also provides release, meaning, or psychological distance (for example, classic suspense, supernatural metaphor, or stories with clear resolution).

- Unhelpful horror can feel too close to real-life pain, especially when it resembles personal experiences (for example, certain forms of realistic violence, abuse narratives, or relentless despair without relief).

- Context matters: the same film can be cathartic on one day and unbearable on another, depending on sleep, stress, and emotional resilience.

A teacher would phrase it like this: the genre is a tool, not a rule. If it helps you process fear with boundaries, it serves King’s point. If it invades your boundaries, it stops being training and becomes overload. Good self-knowledge is part of the message here.

Practical Takeaway: Using the Quote as a Lens for Everyday Life

King’s quote is most useful when you treat it as a lens, not just as commentary on entertainment. It suggests a method: when you feel fear, ask yourself whether the fear is formless or defined. If it is formless—general dread, constant tension, a sense that “something is wrong”—your mind may benefit from giving it shape. Horror stories do that through symbols and plots, but you can do it in everyday thinking as well.

For example, instead of saying “I’m anxious,” you might identify the specific theme underneath: fear of loss, fear of uncertainty, fear of failure, fear of helplessness. Once fear is named, you can respond more intelligently. You can create limits, plans, and supports. That is exactly what horror does at a narrative level: it identifies a threat, explores responses, and shows consequences.

So the practical lesson is not “watch more scary movies.” The lesson is: humans cope better when fear becomes something they can describe and face in manageable steps. Horror is one cultural way of practicing that skill—and King’s line explains why the practice has survived across centuries and media.

You might be interested in…

- Why Stephen King’s “We Make Up Horrors to Cope With the Real Ones” Explains Our Love of Horror

- Why “The Scariest Moment Is Always Just Before You Start” Hits So Hard — Stephen King on Fear, Action, and Momentum

- The Meaning Behind “Amateurs Sit and Wait for Inspiration” — Stephen King on Discipline and Real Creative Work

- “Get Busy Living or Get Busy Dying” Meaning Explained — What Stephen King’s Quote Really Demands From You

- The Meaning Behind “Books Are a Uniquely Portable Magic” — Why Stephen King’s Line Still Matters Today