Quote Analysis

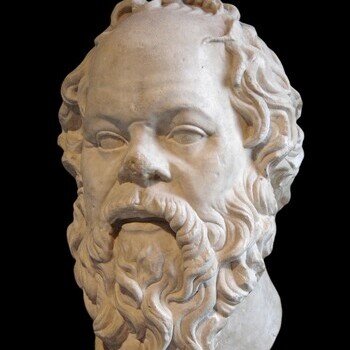

When people feel threatened—by loss, shame, or real danger—the first instinct is often simple: stay alive, no matter what. But that instinct can push someone into choices they later can’t respect: lying to escape consequences, betraying a promise, or doing something unjust just to “get through it.” Socrates draws a sharp line here, reminding us that existence alone isn’t the highest goal. As he put it:

“Not life, but a good life, is to be chiefly valued.”

The question is uncomfortable but necessary: if survival demands that you abandon your principles, what exactly are you saving—and who do you become afterward?

Defining “a Good Life” in Socrates’ Sense

When Socrates talks about “a good life,” he is not talking about comfort, wealth, popularity, or even happiness in the modern self-help sense. He means a life that is morally sound—a life guided by justice, reason, and inner consistency. In plain terms: it’s a life you can respect when you are alone with your own thoughts. Socrates believes that the quality of a life is measured by the quality of one’s choices, especially when those choices are difficult.

To understand this, it helps to separate two different goals: living longer and living rightly. A person can live a long time by avoiding conflict, flattering the powerful, or staying silent when silence is convenient. But Socrates would ask: what happens to your character in that process? A “good life” is not a decorative ideal; it is the foundation of who you are.

A simple way to think about it is this: if you had to explain your decision to a fair-minded judge inside your own conscience, would your reasoning still hold? Socrates pushes us to value a life that stays aligned with truth and justice, because that alignment is what keeps a person whole.

Where the Line Is: Survival at the Price of Principles

Socrates is famous for refusing to treat survival as the highest value. Historically, this makes sense in the context of his trial: he is offered ways to avoid death, but he will not purchase safety by abandoning what he believes is just. The lesson is not “choose death.” The lesson is: do not treat morality like a tool you use only when it is convenient.

In everyday life, the pressure is usually smaller than a courtroom, but the mechanism is the same. Fear makes people bargain with their principles. First it’s a “small lie” to avoid trouble. Then it becomes a habit. Over time, a person can end up protecting their life, their job, or their reputation—while slowly losing their moral clarity. Socrates warns that this is a bad trade.

Here is a practical way to see the boundary:

- Some actions harm only you (taking a difficult path, accepting discomfort, refusing an easy shortcut).

- Some actions harm others (cheating someone, spreading a false accusation, betraying trust, supporting injustice).

- Socrates’ view is that avoiding harm to others and avoiding injustice should be non-negotiable—even under pressure.

Modern example: imagine someone is told to falsify numbers “just this once” or to blame a coworker to save their own position. Socrates would say: if you save yourself by committing injustice, you are not truly saving your life—you are damaging the part of you that makes life worth having.

Dignity as the Foundation of Identity

Socrates treats dignity as something deeper than pride. Pride can be loud and fragile; dignity is quiet and structural. It is the inner standard that tells you, “I will not become that kind of person,” even when fear is shouting. In this quote, dignity is not an accessory—it is the core of identity. If you keep your body safe but lose your moral spine, you are left with a version of yourself that requires constant excuses.

This is why Socrates links “a good life” to character. Character is built through repeated choices, and especially through choices made under pressure. When someone crosses a moral line once, the mind often tries to protect itself by inventing explanations: “I had no choice,” “everyone does it,” “it was necessary.” These explanations may reduce discomfort, but they also train the person to live with contradictions. Over time, the person becomes someone who cannot look clearly at their own actions without defensiveness.

A modern way to phrase Socrates’ insight is: your identity is not only what you claim to believe, but what you are willing to do when it costs you. That cost can be social, professional, or personal. Socrates is teaching that the strongest form of self-respect comes from consistency—when your actions and conscience can stand in the same room without conflict.

Conscience as an “Inner Courtroom” and the Real Cost of Injustice

Socrates treats conscience like a judge that lives inside you. It doesn’t need witnesses, headlines, or punishment from the outside world. It works in silence—usually later, when the noise is gone. This is why he thinks injustice is never a “smart shortcut.” Even if you escape external consequences, you still carry the internal verdict.

Think of it like this: if you do something wrong to protect yourself, you may gain safety, but you also create a problem that follows you everywhere. The mind tries to manage this problem in two common ways. First, it uses excuses: “I had no choice,” “it was just once,” “everyone does it.” Second, it hardens: you stop feeling the discomfort by lowering your standards. Socrates would say both strategies damage the soul—not in a mystical sense, but in a practical one: they weaken your ability to be honest with yourself.

A clear classroom example is cheating. A person might say, “It’s harmless, I just need to pass.” But what they really learn is that truth is optional when pressure is high. Over time, that lesson spreads into other areas: relationships, work, responsibility. Socrates’ point is simple: the deepest cost of injustice is that it trains you to become someone you can’t fully respect.

Applying the Quote Today: Work, Relationships, and Public Life

Socrates is useful because he doesn’t speak only to dramatic moments. Most moral failures do not happen in courtrooms. They happen in normal life, where decisions feel small and private. The quote becomes practical when you use it as a test: “Am I protecting my life, my comfort, or my image by doing something I know is wrong?”

In work settings, the pressure often comes through “soft commands.” A boss may not say, “Lie,” but they may say, “Make it look better,” or “Don’t mention that part.” In relationships, the temptation is often to avoid discomfort: hiding the truth to keep peace, manipulating someone to maintain control, or using guilt to get your way. In public life, the pattern can become collective: people repeat what is popular, not what is true, because belonging feels safer than honesty.

To keep this concrete, here’s an orderly list of modern “Socrates moments”:

- Choosing honesty over convenience (telling the truth even when it makes you look worse).

- Refusing to shift blame (not sacrificing someone else to protect your status).

- Not joining in unfairness (staying out of gossip that destroys reputations).

- Keeping promises under pressure (not rewriting your values when fear appears).

Socrates’ lesson is that these choices shape who you become. A “good life” is built through repeated integrity in ordinary situations, not through a single heroic act.

What Socrates Is Not Saying: Courage Without Seeking Suffering

It’s important to teach this quote correctly. Socrates is not praising pain, and he is not telling people to chase hardship. He is warning against a specific mistake: treating survival and comfort as the highest goal, even when they demand moral collapse. In other words, the point is not “choose the hardest option.” The point is “do not choose injustice as your solution.”

Historically, Socrates becomes the symbol of this idea because he accepts consequences rather than betray what he believes is right. But the practical takeaway is not to copy the dramatic ending. The practical takeaway is to understand priorities: a good life requires moral boundaries. Boundaries are meaningful only when they cost something.

A helpful way to frame it is the difference between courage and recklessness. Courage means you can face discomfort for the sake of what is right. Recklessness means you create suffering to feel noble. Socrates is teaching courage: don’t panic, don’t sell your conscience, don’t become the kind of person who needs constant justification.

Modern example: if speaking up at work risks conflict, Socrates is not saying “burn everything down.” He is saying: find a truthful, fair way to act—because protecting yourself through dishonesty may feel easier today, but it builds a weaker character tomorrow.

You might be interested in…

- What Socrates Meant by “Not Life, but a Good Life, Is to Be Chiefly Valued” — Why Integrity Matters More Than Survival

- The Meaning Behind “I neither know nor think that I know” — Socrates on Intellectual Humility

- The Meaning Behind “The Unexamined Life Is Not Worth Living” — What Socrates Really Meant

- The Meaning Behind “If it were necessary either to do wrong or to suffer it…” — Why Socrates Chose Suffering Over Injustice

- Why Socrates Said “So One Must Never Do Wrong” — The Hardest Test of Moral Consistency