Quote Analysis

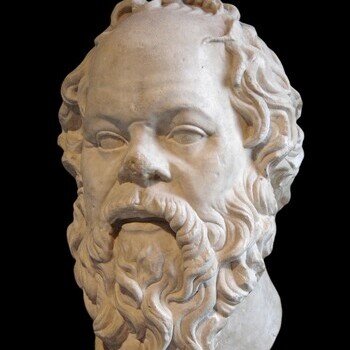

When you’re under pressure, the “easy” option often looks like a shortcut: bend the truth, hit back, game the system, protect yourself at someone else’s expense. Most people fear being harmed more than they fear becoming the one who harms. Socrates flips that instinct on its head and insists that the real danger isn’t what happens to you—it’s what you become when you choose wrongdoing. That’s why he draws a hard line in the famous statement:

“If it were necessary either to do wrong or to suffer it, I should choose to suffer rather than do it.”

It’s not a poetic slogan. It’s a moral ranking: external loss can be painful, but inner corruption is worse—and it lasts longer.

Victim vs. Wrongdoer: Socrates’ Moral Ranking

Most people instinctively think the worst outcome is to be harmed—robbed, betrayed, humiliated, or punished unfairly. Socrates asks you to slow down and separate pain from moral damage. Pain is something that happens to you from the outside. Moral damage is something you do to yourself from the inside. In his view, being a victim can hurt, but it does not automatically make you a worse person. Becoming a wrongdoer, however, shapes your character in a harmful direction.

Historically, this idea fits Socrates’ role in Athens, where public reputation, power, and retaliation were common social currencies. Many citizens believed strength meant “never lose,” and justice often blended with personal payback. Socrates pushes back: real strength is not the ability to strike, but the ability to stay just when striking would be easy.

To make the distinction clearer, think of two situations:

- Someone lies about you and you suffer consequences you didn’t deserve.

- You lie about someone else to protect yourself.

The first is unfair and painful. The second adds something worse: you train yourself to use injustice as a tool. Socrates is saying: if you must choose a loss, choose the loss that doesn’t poison who you are.

Inner Harm: How Doing Wrong Changes the Person You Become

Socrates treats wrongdoing as more than a single bad action. He treats it as a pattern-building force. One dishonest choice rarely stays isolated. It becomes a habit of mind: “If I can get away with it, it’s acceptable.” Over time, that habit reshapes your identity, not just your public image. This is why he considers injustice a kind of self-injury.

Here is the “teacher version” of the mechanism:

- You face pressure (fear, anger, shame, temptation).

- You choose a shortcut (lie, betray, manipulate, retaliate).

- You justify it (“I had to,” “they deserved it,” “everyone does it”).

- Your conscience becomes quieter next time.

In modern life, this is easy to observe. A person who cheats “once” to meet a deadline often finds it easier to cheat again. A person who humiliates someone “just this time” because they’re angry often becomes more comfortable with cruelty. Socrates isn’t saying you will instantly become evil. He is saying your moral sensitivity dulls when you practice injustice.

Philosophically, this connects to his belief that the soul (your inner moral self) matters more than comfort or status. If wrongdoing damages that inner core, then it is rational—yes, rational—to avoid wrongdoing even when it would protect you.

External Loss vs. Internal Cost: What Is the Real Price?

Socrates’ quote only makes sense if you accept a key distinction: external consequences and internal consequences are not the same kind of thing. External consequences are visible—money lost, opportunities missed, public embarrassment, legal trouble. Internal consequences are quieter—self-respect weakened, moral standards lowered, trust in yourself shaken.

Many people treat external loss as the “real” loss because it is measurable. Socrates treats internal cost as more serious because it affects every future decision. If your integrity breaks, you don’t just lose one thing; you lose the tool that keeps your life coherent.

A simple example: imagine you can escape blame at work by shifting it to a colleague. Externally, you might gain safety. Internally, you pay in a different currency: you practice disloyalty, you normalize unfairness, and you start living with the knowledge that your security came from harming someone else. That knowledge often leaks out as anxiety, defensiveness, or cynicism.

Socrates would say: external loss can be repaired or replaced, but internal damage tends to spread. Once you accept injustice as “practical,” it becomes harder to draw lines later.

If you want a clear checklist, it looks like this:

- External loss: temporary, situational, often reversible.

- Internal cost: lasting, identity-shaping, often accumulative.

That is why he chooses to suffer rather than do wrong: he refuses to pay with his character.

Strength as Self-Mastery: Not Doing Whatever You Want

In everyday talk, “strength” often means dominance: the ability to win, control, or strike back. Socrates teaches a stricter definition: strength is self-mastery, the ability to keep your values stable when emotions are loud. In other words, freedom is not “I can do anything,” but “I am not owned by anger, fear, or appetite.”

This matters because impulses feel convincing in the moment. Anger says, “Hit back.” Fear says, “Lie and survive.” Desire says, “Take it now.” Socrates is warning that obeying impulses may look like power, but it is often the opposite: it is being controlled from the inside.

Modern examples are everywhere:

- A quick revenge message online might feel satisfying, but it trains you to react, not to judge wisely.

- A “small lie” to avoid awkwardness seems harmless, but it trains you to manage life through deception.

- Cheating a rule because “the system is unfair” might feel clever, but it trains you to excuse yourself whenever it benefits you.

Socrates’ point is practical: self-mastery protects your long-term character. You may lose comfort today, but you gain something more stable—an inner standard that doesn’t collapse under pressure. That, for him, is what makes a person truly strong.

Applying the Quote Today: Where the “Easy Way” Tempts You

To apply Socrates, you have to look for moments when you feel pushed into a corner—when you tell yourself, “I don’t have a choice.” Those are exactly the moments he is talking about. He is not describing rare heroic scenes; he is describing ordinary crossroads where character is shaped quietly.

In modern life, the temptation usually comes in three disguises:

- Self-protection: “If I tell the truth, I’ll look bad—so I’ll twist the story.”

- Retaliation: “They hurt me first—so I’m allowed to hurt them back.”

- Convenience: “It’s just a small cheat—no one will notice.”

Now think like a careful teacher: what is the real lesson your mind is learning in each case? Not the outcome, but the method. If your method becomes lying, manipulation, or cruelty, you have trained yourself to solve problems in a way that makes you morally weaker.

Examples make this clearer. At work, it can be tempting to shift blame to a colleague to protect your reputation. In relationships, it can be tempting to punish someone with silence instead of speaking honestly. Online, it can be tempting to embarrass someone publicly because you feel justified. Socrates would say: these actions may feel effective today, but they quietly teach you that injustice is a tool—something you use when it benefits you. That is exactly what he refuses to become.

Does Socrates Promote Passivity? Drawing the Line Between Justice and Revenge

A common misunderstanding is to think Socrates is saying: “Let people harm you and do nothing.” That is not the point. Socrates is not praising weakness. He is teaching a boundary: you may resist wrongdoing, but you must not become a wrongdoer in the process. The difference is the difference between justice and revenge.

Justice aims to repair order. Revenge aims to satisfy wounded pride. In ancient Athens, retaliation was often treated as normal—honor culture pushed people to “answer” insults and injuries. Socrates challenges that social reflex. He is saying: your dignity does not need violence or deceit to prove itself.

So what can you do instead of “doing wrong”? You can defend yourself without crossing moral lines. Here are clear options that fit his logic:

- Set boundaries: Say no, step away, block access, reduce contact.

- Use fair procedures: Report, document, ask for mediation, involve rules that apply to everyone.

- Speak plainly: Explain what happened without exaggeration or manipulation.

- Refuse escalation: Do not “match” unethical behavior with unethical behavior.

This is where the short sentence fits perfectly: “So one must never do wrong”. It sounds strict, but it is meant as a compass, not as a slogan. The compass says: protect yourself, but do it in a way you can respect afterward. In Socratic terms, your goal is not to win the moment—it is to keep your moral center intact while you respond.

The Final Lesson: Integrity as an Investment in Your Future Self

Socrates’ moral thinking is long-term. He asks you to imagine that you will have to live with yourself tomorrow, next year, and at the end of your life. That is why integrity matters: it is not just “being good.” It is having an inner standard that makes your life stable, even when circumstances are unstable.

Think of integrity like a foundation. If the foundation is strong, you can face storms without collapsing. If the foundation is cracked, even small problems feel dangerous because you no longer trust your own judgment. Socrates is warning that wrongdoing is not only harmful to others—it makes you unreliable to yourself.

Modern examples show how integrity pays off. A person who refuses to lie becomes someone others can trust, which creates real social strength. A person who refuses to cheat learns that they can handle pressure without shortcuts, which creates confidence that is not fragile. A person who refuses to retaliate unfairly learns emotional control, which prevents many unnecessary conflicts.

Philosophically, this is the heart of Socrates: the good life is not measured by comfort, applause, or advantage. It is measured by whether your choices keep your inner life clean and coherent. When he says he would rather suffer than do wrong, he is choosing to protect the part of himself that guides every future choice. That is why his message still feels demanding today—and why it still matters.

You might be interested in…

- Why Socrates Said “So One Must Never Do Wrong” — The Hardest Test of Moral Consistency

- The Meaning Behind “The Unexamined Life Is Not Worth Living” — What Socrates Really Meant

- What Socrates Meant by “Not Life, but a Good Life, Is to Be Chiefly Valued” — Why Integrity Matters More Than Survival

- The Meaning Behind “If it were necessary either to do wrong or to suffer it…” — Why Socrates Chose Suffering Over Injustice

- The Meaning Behind “I neither know nor think that I know” — Socrates on Intellectual Humility