Quote Analysis

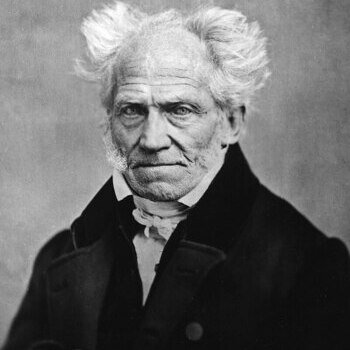

When Arthur Schopenhauer opened his magnum opus The World as Will and Representation with the striking line:

“The world is my representation,”

he wasn’t simply being poetic. He was laying the cornerstone of his entire philosophy: the claim that reality, as we know it, exists only through our perception. This idea challenges our most basic assumptions about objectivity and truth. Are we ever capable of knowing the world “as it is,” or are we forever confined to the lens of our own consciousness? Let’s unpack the depth and meaning behind this influential statement.

Introduction to Schopenhauer’s Philosophy

Arthur Schopenhauer is often described as one of the most influential yet misunderstood thinkers of the 19th century. To appreciate his statement “The world is my representation”, it is necessary to situate him within the broader history of philosophy. Schopenhauer lived in a period when German philosophy was dominated by Kant’s critical system and Hegel’s complex idealism. Unlike Hegel, who believed history was guided by reason’s progress, Schopenhauer took a far more skeptical and even pessimistic stance.

He argued that philosophy should begin with the undeniable fact of human experience: everything we know is filtered through our mind. This means that instead of assuming an external world “out there,” Schopenhauer invites us to examine how the world is presented to us as conscious beings.

His perspective is not abstract speculation; it touches everyday life. When you see a tree, you do not access the “tree in itself,” but rather your mind’s representation of it. This insight sets the stage for his later reflections on will, suffering, and compassion. In short, this opening line announces a philosophy that shifts the focus from objective reality to the structures of perception and consciousness.

The Meaning of “World as Representation”

When Schopenhauer says that the world is our “representation,” he is using a technical term. Representation refers to all objects of our experience — everything we perceive, imagine, or think about. It includes not only sensory impressions, such as colors, sounds, or shapes, but also the categories through which our mind organizes them. The claim is radical because it asserts that there is no world apart from this network of representations. The world does not simply exist independently and then appear to us; it exists for us only through the act of appearing.

To make this clearer, consider everyday examples.

- When you hear music, what you actually perceive is a sequence of sounds shaped by your auditory system.

- When you look at a landscape, you see colors and forms processed by your vision, not the raw “things” themselves.

- Even abstract concepts like justice or beauty exist as mental constructs shaped by language and culture.

This does not mean that Schopenhauer denies an external reality altogether. Rather, he insists that what we can know of it is limited to its appearance within consciousness. His insight challenges the assumption of objectivity that guides much of science and daily reasoning. Instead of granting us direct access to reality, our senses and intellect mediate everything. Thus, the “world as representation” is a reminder that knowledge is always perspectival — bound by the limits of human cognition.

Subject and Object – The Basic Division of Experience

One of Schopenhauer’s key insights is the strict division between subject and object. The subject is the one who perceives; the object is whatever is perceived. This duality is the very framework of human experience. Without a perceiving subject, no object can appear. Conversely, without objects to perceive, the subject would remain an empty point of awareness. In other words, both terms are inseparable, yet they never merge.

Think of it in everyday terms. When you look at a painting, the painting itself is the object, while your awareness of it is the subject. You cannot trade places; the painting cannot suddenly become the perceiver, and you cannot become the object hanging on the wall. Schopenhauer stresses that this relationship defines the structure of all knowledge.

Philosophically, this distinction highlights the limits of human cognition. We never experience the subject directly — we are the subject. Similarly, we never access objects outside of their presentation to us. This duality underlines his claim that the world exists only as representation. Modern philosophy and cognitive science echo this by emphasizing the role of the observer. For example, in psychology, perception is studied not as passive reception but as active construction: the brain interprets stimuli, filling in gaps and filtering data. Schopenhauer anticipated this line of thought long before it became a scientific consensus.

Connection with Kant’s Philosophy

To fully understand Schopenhauer’s phrase, we must recall the strong influence of Immanuel Kant. Kant distinguished between phenomena — the world as it appears to us — and noumena, or the “thing-in-itself” that lies beyond our capacity to know. Schopenhauer adopts this framework but gives it his own twist. While Kant held that noumena might exist, though unknowable, Schopenhauer insists that for human beings the world is nothing but phenomena — nothing but representation.

Consider an analogy. If Kant tells us we can only see the “surface” of reality, Schopenhauer goes further and says: the surface is all we will ever have, because we are beings bound to perception. This makes his philosophy more radical and, in many ways, more unsettling.

Historically, this stance placed him in contrast with Hegel, who believed reason could grasp absolute truth. Schopenhauer rejected this optimism, arguing that philosophy should remain grounded in the limits of human experience. Today, we can relate his position to modern debates in physics and neuroscience. For example, even scientific models, such as atoms or black holes, are representations constructed through instruments and theories; they are not the “things-in-themselves.”

Consequences for Understanding Reality

Schopenhauer’s claim that the world exists only as representation has profound consequences for how we think about reality itself. If everything we know is shaped by the way our mind processes experience, then we must accept that what we call “objective reality” is never grasped in a pure, untouched form. Instead, we always deal with appearances as filtered through perception, memory, and thought. This view leads to a philosophical position often called epistemological modesty: the recognition that our knowledge has boundaries.

To bring this down to a simple example, imagine wearing tinted glasses. No matter where you look, the world will always have that tint. Similarly, our consciousness is the lens through which everything is seen. You may believe you are perceiving things exactly as they are, but in fact you are seeing them as they appear to you.

This understanding has two main implications:

- It questions the certainty of absolute truths. If perception is always perspectival, then truth is not universal but conditioned by human faculties.

- It emphasizes the role of the individual observer. Each person carries a slightly different lens, shaped by biology, culture, and personal history.

Modern science echoes these insights. In quantum physics, the act of observation influences the result. In psychology, cognitive biases show how the mind organizes information selectively. Schopenhauer’s idea therefore remains relevant, reminding us that reality is never detached from the act of perceiving it.

Critiques and Dilemmas

Schopenhauer’s radical subjectivism has not gone unchallenged. Many philosophers argue that if the world is only representation, then this view risks collapsing into solipsism — the belief that only one’s own mind exists. If everything is representation, how can we account for the independent existence of other people or the external world? This is one of the dilemmas his philosophy raises.

Critics also suggest that his position underestimates the stability and consistency of reality. For instance, even if perception varies from person to person, we can all agree that fire burns or that gravity pulls objects downward. These shared experiences point to something more than just private representations.

Schopenhauer attempted to address these concerns by introducing the concept of the “will” as a deeper layer of reality. While the world appears to us as representation, it is driven at its core by a universal, blind striving he calls the will. This move allows him to avoid pure solipsism and to explain why we recognize common structures in experience.

From a modern perspective, his dilemmas connect with debates about virtual reality and artificial intelligence. If machines create simulated worlds indistinguishable from reality, does that reduce our own world to a mere set of representations? Schopenhauer’s framework makes us confront such questions directly. His critics remind us of the need to balance the subjective with the intersubjective — the recognition that while we live in our own representations, we also share a common world.

Ethics and Life Philosophy in the Light of the Quote

Schopenhauer’s statement that “the world is my representation” is not only a claim about knowledge but also the foundation for his ethics and view of life. If everything we know comes through our perception, then recognizing the limits of our viewpoint should lead us to humility and compassion. Schopenhauer emphasizes that all living beings experience suffering through the same mechanism of representation: pain, loss, and desire are not external abstractions but internal realities of consciousness.

From this follows an ethical insight: since suffering is universally present, empathy becomes the moral response. When I realize that another person’s pain is as real in their representation of the world as my pain is in mine, I gain a reason to treat them with kindness. This explains why Schopenhauer admired Eastern philosophies such as Buddhism and Hinduism, which also highlight compassion and detachment from selfish desires.

His life philosophy, shaped by this worldview, is essentially one of modesty and restraint. Rather than striving endlessly for wealth or recognition, Schopenhauer suggests that peace comes from lowering our desires and reducing our attachment to illusions of absolute control. Modern psychology has found a parallel in mindfulness practices, where individuals learn to observe thoughts and emotions without clinging to them. In both traditions, the recognition that the world is shaped by perception becomes the basis for a gentler, more ethical way of living.

Influence and Interesting Connections

The idea that “the world is my representation” had a lasting impact far beyond philosophy. It shaped literature, music, and even later developments in science. Writers such as Thomas Mann and Marcel Proust drew inspiration from Schopenhauer’s notion of subjectivity when exploring the inner worlds of their characters. Richard Wagner, the composer, explicitly acknowledged Schopenhauer’s influence, translating the idea of suffering and will into dramatic operatic form.

Philosophically, the statement anticipated many later debates about perception and reality. Existentialists like Jean-Paul Sartre and phenomenologists like Edmund Husserl revisited similar themes, asking how consciousness structures the world we experience. In modern philosophy of mind, discussions about whether reality is constructed or discovered often echo Schopenhauer’s insights.

Interesting parallels can also be drawn with contemporary science and technology. In neuroscience, research shows that perception is an active construction: the brain fills in gaps, interprets signals, and even generates illusions. In virtual reality technologies, users experience fully convincing “worlds” that are nothing more than digital representations. These examples make Schopenhauer’s claim surprisingly modern, showing that his 19th-century insight continues to resonate in the 21st century.

Finally, Schopenhauer’s connection to Eastern thought cannot be overlooked. He admired Buddhist teachings that deny an absolute, independent reality and stress the primacy of consciousness. This cultural bridge highlights the universality of the idea: across traditions, human beings have wrestled with the fact that reality is always mediated by perception. Thus, the quote stands as a crossroads where philosophy, art, and science meet, each finding new meaning in the thought that the world is, at its core, representation.

You might be interested in…

- “Compassion Is the Basis of Morality” – Schopenhauer’s Radical View on Ethics

- “The Person Who Writes for Fools Is Always Sure of a Large Audience” – Schopenhauer’s Sharp Critique of Mass Culture

- The Limits of Vision in Schopenhauer’s Philosophy – What He Meant by ‘Every man takes the limits of his own field of vision for the limits of the world’

- “The World Is My Representation” – Understanding Schopenhauer’s Radical View of Reality

- “Man Can Do What He Wills but He Cannot Will What He Wills” – Schopenhauer’s Challenge to Free Will