Quote Analysis

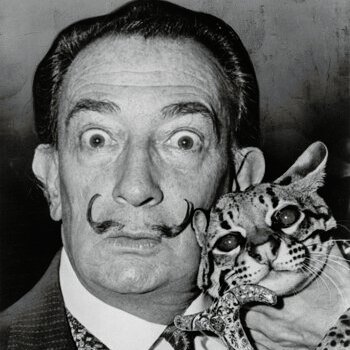

When Salvador Dalí declared:

“The only difference between me and a madman is that I am not mad.”

He wasn’t simply being eccentric, he was making a philosophical statement about the thin line between genius and insanity. Dalí’s surrealism was not a descent into madness but a conscious exploration of it — a journey into the subconscious with full awareness of his steps. This paradoxical quote invites us to ask: can creativity exist without chaos, or is chaos the very source of it?

Dalí Between Genius and Madness

When Salvador Dalí spoke about the difference between himself and a madman, he was not mocking mental illness — he was defining the limits of artistic consciousness. To understand this, we need to imagine the artist as someone walking on a very thin rope between two worlds: the rational and the irrational. Dalí dared to enter the world of dreams, hallucinations, and subconscious impulses, but unlike a madman, he always knew he was walking through them. This self-awareness is what separates creative imagination from real psychosis.

In his surreal paintings — melting clocks, floating elephants, disjointed landscapes — Dalí revealed that logic can be expanded, not destroyed. His goal was not chaos for its own sake, but revelation: to show that behind irrational images lies another kind of truth. Like a scientist experimenting with matter, Dalí experimented with the human mind. The difference is that his laboratory was the imagination, and his tools were paradox and irony.

Even today, his message remains relevant. In an age where creativity is often limited by conventions, Dalí teaches that true originality demands courage to approach mental “madness,” but with intellectual discipline. The genius, therefore, is not the one who avoids the irrational, but the one who transforms it into meaning.

The Philosophical Roots of the Quote

Behind Dalí’s humor and eccentricity lies a serious philosophical foundation — one deeply influenced by Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis. Freud believed that the human mind consists of conscious and unconscious layers. What we repress — our fears, desires, and instincts — doesn’t disappear; it hides in dreams and symbols. Dalí found in this theory an artistic key. He realized that if we can visualize those unconscious images without losing control, we can access a deeper, more authentic layer of reality.

Surrealism, the movement Dalí helped define, was built on this idea. It aimed to unite reason and dream, order and chaos, without letting one destroy the other. Dalí’s quote expresses that balance perfectly: he recognizes the madness of his visions but claims ownership over them. He turns what could be psychological instability into aesthetic creation.

In modern terms, we could compare Dalí’s approach to controlled innovation. Just as scientists or inventors use risky ideas but test them systematically, Dalí used his subconscious responsibly. He was the rational explorer of irrational territory. His words remind us that to truly understand ourselves — whether in art, science, or philosophy — we must dare to face what we don’t fully understand, but never surrender to it.

The Thin Line Between Insight and Insanity

To understand Dalí’s statement about madness, imagine that creativity and insanity are two sides of the same coin — separated only by self-awareness. A madman is overwhelmed by his imagination; he cannot distinguish fantasy from reality. A creator, on the other hand, steps into imagination consciously, explores it, and then returns to share what he found. Dalí was fully aware of this distinction. His art may look irrational, but it is the product of deliberate design. Every distorted form and impossible perspective carries intention, not confusion.

This idea appears throughout history. Thinkers like Plato and Nietzsche both described the artist as someone “touched by divine madness.” Yet Dalí adds a modern twist — the artist must not only be inspired but also lucid. He is like a diver who descends into dark waters but knows how to resurface before drowning. In practical terms, that means controlling the impulses of the mind rather than being ruled by them.

Today, we can see this principle in psychology and even in innovation. Many visionaries — from writers to scientists — operate at the edge of reason, taking creative risks that others would consider absurd. The difference lies in discipline: the ability to observe one’s own thoughts without being consumed by them. Dalí’s “madness” is not sickness but method — a controlled exploration of the irrational as a path to understanding the human mind.

The Ego and Self-Awareness in Creation

Dalí’s ego was not merely vanity; it was his compass. He cultivated a strong sense of identity because he understood that only a well-defined self can navigate the chaos of imagination without losing direction. When he exaggerated his persona — the mustache, the theatrics, the self-declared genius — it was part of a conscious act. Dalí turned his own ego into an art form, a protective mask that allowed him to confront inner chaos without being overwhelmed by it.

This self-awareness reflects a broader philosophical truth: creation requires both detachment and immersion. The artist must be able to look at his thoughts as if they belong to someone else. That’s what Dalí mastered — he could observe his dreams without identifying with them. He once said that he painted his dreams “with the precision of a photograph,” which shows that even his most irrational visions were grounded in control and observation.

In psychological terms, this can be compared to metacognition — the ability to think about one’s own thinking. Dalí’s awareness of his mental processes made him not only a painter but also a philosopher of perception. His art teaches us that ego, when balanced, is not an obstacle but a stabilizing force in the creative process. The self becomes both the lens and the anchor — the point from which imagination can safely expand into infinity.

Surrealism as a Philosophical Laboratory

To understand Dalí’s surrealism, it’s essential to see it not merely as an art movement, but as a form of philosophical experimentation. Surrealism sought to bridge two worlds — the rational and the dreamlike — in order to reveal hidden aspects of human consciousness. Dalí treated the canvas like a laboratory table where reason and chaos could interact. Each painting was an experiment in perception: how far can the mind stretch reality before it collapses into nonsense?

His surrealist works are filled with symbols — melting clocks, fragmented bodies, and barren deserts — that reflect the instability of time, identity, and memory. These weren’t random images. They were deliberate visual metaphors created through disciplined imagination. Dalí once famously said, “I don’t do drugs. I am drugs,” meaning that his mind itself could induce altered states of perception. He didn’t need external chaos; he generated it consciously and turned it into structured beauty.

Philosophically, this places Dalí among thinkers who believed that imagination can serve as a tool for truth. Like Nietzsche’s “will to power” or Jung’s “active imagination,” Dalí’s surrealism was a method of introspection — a way to explore the unconscious without losing control. In this sense, his art was both scientific and mystical: an inquiry into what the mind can know when freed from ordinary logic but still guided by awareness.

A Lesson for the Modern Creator

Dalí’s message extends far beyond the world of art. He reminds us that creativity is not the absence of order but the intelligent use of disorder. Many people fear their own unconventional thoughts, believing that logic and professionalism demand restraint. Dalí challenges this view by showing that true innovation begins where predictability ends. The goal is not to destroy structure, but to reshape it with courage and insight.

For modern creators — writers, designers, scientists, even entrepreneurs — his philosophy can be summarized through three key ideas:

- Embrace curiosity: Explore what feels absurd or illogical; it may hide new solutions.

- Maintain awareness: Observe your creative process like a scientist — test, refine, repeat.

- Balance control and spontaneity: Let ideas flow freely, but guide them with reason.

Dalí’s own life offers a vivid example. His eccentric behavior was not aimless rebellion; it was strategic. He built a persona that symbolized artistic freedom while maintaining strict technical discipline. This combination — wild imagination under conscious control — is what made his art timeless. In a society that often demands conformity, Dalí’s “madness” is a call to intellectual bravery: to think differently without losing clarity.

Controlled Madness as Creative Wisdom

In the end, Dalí’s famous statement about madness is a lesson in philosophical maturity. Madness and genius, he suggests, are not opposites but neighbors separated by awareness. The artist who dares to face the irrational and return with meaning performs an act of wisdom, not insanity. Dalí’s entire career demonstrates that “controlled madness” is the foundation of profound creativity.

We can view this idea through three layers:

- Psychological: The conscious mind directs the unconscious rather than being ruled by it.

- Artistic: Chaos becomes material — it is shaped into images, form, and beauty.

- Ethical: Responsibility remains with the creator; awareness prevents harm and self-destruction.

Dalí mastered this triad. His control over his “madness” made him both provocateur and philosopher. He teaches us that the mind’s chaos isn’t something to suppress but to understand. When awareness meets imagination, the result is not confusion but insight. His paradox — that sanity can exist within madness — captures the essence of human creativity: to enter disorder, organize it through consciousness, and emerge with art that speaks the language of both dream and reason.

You might be interested in…

- “Surrealism Is Destructive, but It Destroys Only What It Considers to Be Shackles Limiting Our Vision” – Salvador Dalí’s Call to Free the Mind

- “The Only Difference Between Me and a Madman Is That I Am Not Mad” – Salvador Dalí’s Paradox of Controlled Chaos

- The Deeper Meaning Behind Salvador Dalí’s Quote: “A true artist is not one who is inspired, but one who inspires others.”

- The Meaning Behind “I Don’t Do Drugs. I Am Drugs.” – Salvador Dalí’s Surreal Vision of Creativity

- “Have No Fear of Perfection – You’ll Never Reach It” – Salvador Dalí’s Message About Creative Freedom