Quote Analysis

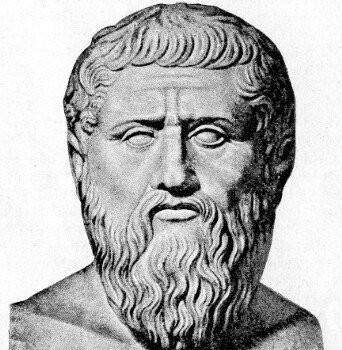

In Plato’s Phaedo, Socrates is waiting for execution and speaking about the soul, truth, and what it means to live well when life becomes uncontrollable. In that tense setting, he asks a disturbing but surprisingly practical question:

“Is not philosophy the practice of death?”

At first glance, it sounds bleak—almost like a rejection of life. But Plato isn’t praising darkness or obsession with dying. He’s pointing to a kind of training: learning to detach from whatever enslaves you—fear of loss, obsessive desire, approval-seeking, and the panic of needing everything to go your way. So what did Plato really mean by “practicing death,” and why can this idea feel strangely modern today?

Central Idea of the Quote

Plato’s question—“Is not philosophy the practice of death?”—uses the word death as a teaching tool, not as a dark obsession. In Phaedo, “death” points to separation: the moment when everything we cling to can be taken away. Plato is basically saying: if you want to live wisely, you must train your mind to loosen its grip on the things that control you.

Think of “practicing death” as practicing inner independence. A person who cannot tolerate losing comfort, status, or approval is easy to manipulate. They may say they value truth, but the moment truth becomes inconvenient, they hide it, soften it, or trade it away. Plato wants the opposite: a character that can stay steady even when life becomes uncomfortable.

To make this concrete, notice what usually “kills” our freedom long before the body dies:

- Fear of losing people, money, or reputation

- The urge to be liked and praised

- The need to control every outcome

- Addictive habits that calm anxiety for a moment but weaken the mind

So the “practice” here is not about death itself—it is about removing the chains that make us panic. Philosophical life, for Plato, means learning to prefer what is true over what is easy.

Historical Context: Socrates in the Phaedo

This line hits differently because of where it appears. In Phaedo, Socrates is not giving abstract advice at a safe distance—he is speaking while waiting for his execution. That matters because philosophy is being tested under pressure. Many people can sound wise when nothing is at stake. Socrates is calm when everything is at stake.

Plato uses this moment to show a clear contrast between two ways of living. One way is built on external supports: comfort, social approval, security, and control. When those supports shake, the person collapses—emotionally and morally. The other way is built on inner order: the ability to think clearly, to keep values stable, and to face reality without self-deception. That is the kind of person Socrates represents in the dialogue.

Socrates’ calmness does not mean he “doesn’t care.” It means he has trained himself not to let fear command him. He is not pretending that death is pleasant. He is showing that a person can meet a hard truth without becoming a slave to panic.

Historically, the dialogue also reflects a major Greek concern: the difference between appearance and reality. Socrates’ trial and death are full of politics, misunderstanding, and public opinion. Plato is quietly teaching: if your identity depends on the crowd, you will never be free. Philosophy, in this scene, is the long training that prepares you to stand by reason even when the world turns against you.

What “Detachment” Really Means in Practice

When Plato speaks about separating the soul from the body, many readers think he is attacking ordinary life—food, pleasure, relationships, emotions. That is too simplistic. The practical point is not “hate the body.” The point is: do not let impulses and fears become your rulers. Detachment is not coldness; it is self-control.

A good way to understand this is to compare two people facing the same problem. Imagine someone loses a job. One person immediately panics because their self-worth is built on status. Another person feels stress too, but they can think: “This is painful, but it doesn’t define me. I will act wisely.” Plato calls that second ability a sign of a freer soul.

Detachment, in Plato’s sense, means training yourself to separate:

- What is true from what is merely comfortable

- What you can control (choices, honesty, effort) from what you cannot (other people’s reactions, luck, timing)

- What you are (character, judgment) from what you have (titles, praise, possessions)

In modern life, this shows up everywhere: doom-scrolling, approval addiction, fear of missing out, and the constant urge to “manage” how others see you. Plato would say: these are not small habits—they are chains. “Practicing death” is practicing the ability to lose something without losing yourself. That is why the quote sounds extreme: it is meant to wake you up.

Common Misreadings—and What Plato Is Not Saying

Because the quote contains the word “death,” people often misunderstand it in predictable ways. A teacherly approach is to separate the sound of the sentence from its lesson. Plato is not building a cult of gloom. He is correcting a very human mistake: confusing what is “alive” with what merely feels intense.

One common misreading is: “Philosophy is about rejecting life.” That is not the point. Plato is not telling you to stop enjoying food, friendship, or beauty. He is warning that pleasures become dangerous when they turn into chains. If you cannot say “no” to something, that thing is no longer a simple pleasure—it is a master.

Another misreading is: “This is just religious talk about the afterlife.” It’s true that Phaedo includes arguments about the soul. But even if you set metaphysics aside, the practical message still stands: train your mind so it does not panic when comfort disappears.

A third misreading is: “Detachment means being emotionless.” Plato’s ideal is not a stone statue. The aim is emotional discipline, not emotional absence. The difference is huge: discipline means you feel fear or grief, but you can still think and act wisely.

If you want a clean summary, keep these points:

- Plato is teaching freedom from inner slavery, not love of death.

- The quote is about training, not about despair.

- The “practice” is learning to face loss without losing judgment.

Modern Relevance: Principles, Pressure, and the Collapse of Plans

To understand why this idea still matters, translate it into modern situations where people “die” psychologically—when their identity collapses because something external changes. Plato’s “practice of death” is really practice for those moments.

Consider how often people compromise themselves under pressure. A person says they value honesty, but lies to avoid embarrassment. Someone claims they value health, but keeps habits that destroy energy and self-respect. Another says they value family, but lets pride or addiction run the home. Plato would ask: Who is ruling you—your reason or your impulses? That is the practical battlefield.

This is where philosophy becomes training for character. Not by giving you fancy words, but by making you rehearse a hard skill: staying loyal to what is right when the reward is not immediate.

Here are strong modern examples of what “practicing death” looks like:

- Accepting that some outcomes will not match your plan—and not turning bitter.

- Choosing a long-term principle over short-term comfort (for example: telling the truth even if it costs you).

- Handling criticism without collapsing into people-pleasing or revenge.

- Learning to lose status, money, or approval without losing self-respect.

Plato’s point is that the person who depends on external stability is fragile. The person who depends on inner clarity is resilient. Until philosophers are kings, or philosophers are kings… —even this famous political line connects to the same lesson: society improves when reason leads, not appetite and fear.

The Final Lesson: A “Good Soul” Is More Stable Than Circumstances

Plato’s deeper claim is bold but simple: what you are matters more than what you have. In his view, a “good soul” is not a mystical label—it is a mind trained to see clearly and choose consistently. That kind of inner structure makes a person harder to break.

Think of stability the way you think of physical balance. If your center of gravity is low, you can be pushed without falling. If it is high and unstable, even a small shove knocks you down. Plato argues that most people build their “center” outside themselves—on reputation, possessions, romance, success, being admired. That center is always shaky because the world is always changing.

A “good soul,” by contrast, is anchored in things less fragile:

- Clear judgment (the ability to tell truth from self-deception)

- Self-control (not being ruled by cravings and panic)

- Consistency (acting the same way when watched and when alone)

- Courage (facing reality without running into distractions)

This does not make someone perfect or immune to pain. It makes them harder to corrupt and harder to manipulate. And that is the “practice” Plato is praising: preparing yourself, step by step, to meet change—loss, endings, uncertainty—without selling your integrity. In that sense, philosophy is not a hobby. It is a training for the most serious moments of life.

You might be interested in…

- Why Plato’s “Education is the art which will effect conversion…” Still Matters Today – Learning as a Change of Direction

- The Meaning Behind “Is Not Philosophy the Practice of Death?” — Plato’s Lesson on Inner Freedom

- Why Plato’s “Until philosophers are kings…” Still Matters: Power, Wisdom, and Leadership

- The Meaning of “Justice Was Doing One’s Own Business” — Plato’s Warning Against Being a “Busybody”

- The Meaning Behind “At the Touch of Him Every One Becomes a Poet…” — Plato’s Idea of Love as a Creative Force