Quote Analysis

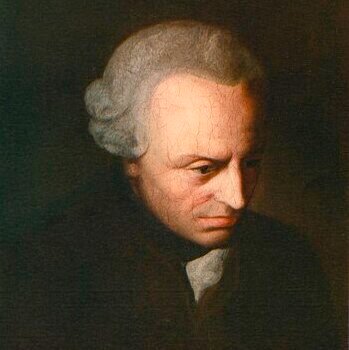

What is the role of happiness in our moral decisions? Should we pursue what makes us feel good—or what reason tells us is right? These questions lie at the heart of Immanuel Kant’s bold statement:

“Happiness is not an ideal of reason but of imagination.”

With this powerful line, Kant draws a sharp line between ethical duty and emotional satisfaction. While many philosophers place happiness at the core of ethical life, Kant insists that true morality requires something deeper than subjective feeling. In this article, we’ll explore what Kant really meant—and why this quote still challenges modern assumptions about happiness.

The Meaning of the Quote: What Is Kant Really Saying?

To understand this quote, we need to carefully unpack Kant’s use of the words “ideal,” “reason,” and “imagination.” At first glance, it might sound like Kant is dismissing happiness as something unimportant—but that’s not his point. Instead, he is drawing attention to the fact that happiness, unlike moral principles, cannot be objectively defined or universally applied.

In Kant’s philosophy, an ideal of reason is something that reason can guide us toward through logical thinking, such as moral duty or universal law. These ideals are based on rational principles that apply to all people, in all situations, regardless of individual feelings. In contrast, imagination refers to the personal and emotional ideas we form in our minds—ideas that vary from person to person.

So when Kant says that “happiness is not an ideal of reason,” he means that reason alone cannot define or guarantee happiness. Happiness is shaped by personal desires, cultural influences, and our individual imagination. One person may imagine happiness as a life of adventure, while another may imagine it as a peaceful family home. Reason has no formula to determine what will make each person happy because happiness is not a fixed, rational concept—it is imagined, fluid, and highly subjective.

By making this distinction, Kant is also reminding us that if we base our moral decisions only on what we believe will bring us happiness, we are not acting according to reason—but rather according to our imagination. And since imagination can deceive us, it is an unreliable foundation for morality.

Kant’s Ethics: Duty Over Desire

Immanuel Kant is one of the most influential figures in moral philosophy, and his ethical system is built on a very specific idea: that morality must be rooted in duty, not in the pursuit of personal happiness. This view may feel strict, or even counterintuitive, especially in a world where “doing what makes you happy” is often considered the highest goal. But Kant’s perspective offers a deeper, more stable approach to ethics.

According to Kant, moral actions are those performed out of respect for the moral law, which he defines using what he calls the categorical imperative. One version of this imperative tells us to act only in ways that could be turned into a universal law—something everyone could reasonably do in the same situation. Importantly, the motivation for acting morally should not come from what we hope to gain (like praise, reward, or happiness), but from a sense of obligation to do what is right.

Here’s why this matters: if we base our moral behavior on the hope of being happy, then our actions are ultimately self-serving. We might act kindly just to feel good about ourselves, or tell the truth only when it benefits us. Kant argues that such behavior is not truly moral, because it depends on conditions and outcomes. True morality, in his view, is unconditional—it requires us to do the right thing even when it doesn’t lead to happiness.

In this way, Kant draws a clear line: happiness is a personal goal, but morality is a rational duty. While happiness can be influenced by luck, emotions, and personal taste, moral duty comes from reason and is the same for all rational beings. This does not mean that Kant is against happiness. Rather, he is warning us that using happiness as a moral compass is dangerous, because it can easily lead us away from what is universally right.

Why Happiness Is Not an Ideal of Reason

To understand why Kant claims that happiness is not an ideal of reason, we need to focus on what reason is meant to do in his moral philosophy. In Kant’s system, reason is not designed to chase feelings, desires, or outcomes—it is designed to guide us toward universal principles that are always valid, no matter our personal goals or emotional states.

Happiness, however, doesn’t follow clear or universal rules. What brings happiness to one person may bring misery to another. For example:

- Some people imagine happiness as career success; others imagine it as spiritual peace.

- One person feels fulfilled through adventure; another prefers stability and routine.

- What makes us happy at age 20 may no longer satisfy us at age 50.

Because of this variation, reason cannot logically define happiness as a consistent goal for all people. It lacks the clarity, predictability, and objectivity that reason demands in moral reasoning. You can’t build a universal law based on something as personal and changing as happiness.

Kant also believed that tying morality to happiness would weaken our commitment to doing what’s right. Imagine someone who helps others only when they feel good about it, but stops when they’re tired or angry. That behavior, Kant would say, lacks moral worth. True moral action must come from a firm principle, not from changing moods or imagined rewards.

In short, reason requires consistency, while happiness is flexible and imagined. That is why happiness cannot serve as an “ideal” for reason to aim at. Instead, Kant tells us, reason should aim at moral duty, which can be applied by all rational beings, in all situations, without exception.

The Role of Imagination in Our Idea of Happiness

Kant’s statement that happiness is an “ideal of imagination” may sound poetic, but it carries a sharp philosophical insight. He wants us to recognize that much of what we call “happiness” is not based on logic or facts—it is shaped by our inner world, our fantasies, and the stories we tell ourselves.

Let’s break this down.

Imagination creates pictures of the life we think we want. These images are often influenced by:

- Cultural messages (e.g., movies, social media, advertising)

- Personal memories and past experiences

- Social comparisons (e.g., what others have or appear to enjoy)

- Emotional desires such as love, recognition, comfort, or power

None of these sources are necessarily rational. For example, someone may imagine that being famous will make them happy, even though fame often brings stress and isolation. Another may imagine that buying a big house will bring peace, only to discover it adds pressure. In both cases, imagination creates a vision of happiness that may be misleading or even harmful.

Kant’s point is not that imagination is bad—it’s that we must recognize its limits. If we let our imagined ideals of happiness dictate our moral choices, we risk chasing illusions instead of living with integrity.

This is especially relevant in today’s world, where people are constantly exposed to idealized versions of life. Social media, in particular, encourages us to imagine happiness as a perfect image: the flawless body, the exotic vacation, the luxurious lifestyle. But these are not moral ideals—they are products of imagination, shaped by desires and appearances, not by reason.

Is Happiness Opposed to Morality?

This is a common question students ask when first reading Kant: Is he saying that to be moral, we must give up happiness? The answer is more nuanced than a simple yes or no.

Kant is not against happiness. In fact, he believes that every human being naturally seeks happiness, and that this desire is legitimate. The issue is not the pursuit of happiness itself, but the role it plays in moral decision-making.

Morality, in Kant’s system, must be based on pure practical reason—which means doing the right thing for the right reason, regardless of personal benefit. If our motivation to act morally depends on whether we’ll be happy as a result, then it’s not truly moral; it’s just self-interest in disguise.

Let’s look at a few practical examples:

- If you tell the truth only because you want others to trust you, your action is conditional.

- If you help someone only because it makes you feel good, you’re still aiming at emotional reward.

These actions might look moral on the outside, but Kant would say they lack moral worth because the motivation is tied to happiness, not duty.

That said, Kant does not claim that happiness and morality are enemies. In an ideal world, a morally good person would also be happy. But because life is unpredictable, we cannot guarantee that moral actions will lead to happiness. And that’s why we must be prepared to do what is right even when it brings discomfort, sacrifice, or hardship.

So, morality is not opposed to happiness—but it must remain independent of it. True moral strength is shown when a person follows duty even in the absence of reward.

What This Quote Means in Today’s World

Kant’s quote may come from the 18th century, but its message is more relevant than ever in the 21st. In a culture obsessed with positivity, self-fulfillment, and lifestyle goals, we often confuse pleasure with meaning, and comfort with moral success. That’s exactly why Kant’s distinction still matters.

Think about how often modern life encourages us to chase happiness through:

- Consumer goods and material success

- Social validation through likes and follows

- Experiences that offer escape or entertainment

- Personal branding and performance of “success”

Each of these reflects an imagined picture of happiness—one shaped by media, marketing, and comparison. But rarely do we stop to ask: Is this truly good? Is it right? Or is it just satisfying in the moment?

Kant warns us that relying on imagination to define happiness can lead us away from real moral development. His ethical framework pushes us to act from principle, not impulse, and to focus on duty, not reward.

His earlier quote captures the same spirit: “Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-imposed immaturity”—which means learning to think for ourselves, beyond emotion and authority, and taking responsibility for our moral choices.

In a world full of distractions and ready-made dreams, Kant invites us to become mature, rational, and self-guided individuals. And that starts by understanding that happiness, while deeply human, should never be the measure of what is right.

Wisdom in the Separation

Kant’s insight into the difference between reason and imagination is not meant to discourage us from being happy. On the contrary, it is meant to elevate our understanding of what matters most. When we confuse happiness with morality, we risk becoming slaves to our desires, moods, and expectations. But when we ground our lives in reason, we begin to act from clarity and strength.

To live a meaningful life, Kant would argue, we must learn to separate what is pleasant from what is right, and not let our fantasies shape our ethics. This doesn’t mean we must live without joy—but that our joy should flow from integrity, not the other way around.

In the end, Kant challenges us to ask hard questions:

- Are we living according to principle—or convenience?

- Are we pursuing truth—or comfort?

- Do we use reason to guide us—or imagination to soothe us?

His famous quote, “Happiness is not an ideal of reason but of imagination,” is more than a philosophical observation—it is a call to personal growth. And like all of Kant’s moral philosophy, it reminds us that the path to true freedom lies not in chasing happiness, but in becoming worthy of it.

You might be interested in…

- “Science Is Organized Knowledge, Wisdom Is Organized Life” – What Immanuel Kant Taught Us About Living Intelligently

- “Happiness Is Not an Ideal of Reason but of Imagination” – Kant’s Radical View on Morality and Emotion

- What Kant Really Meant by “Act Only According to That Maxim…” – A Deep Dive into the Categorical Imperative

- “The Starry Heavens Above Me and the Moral Law Within Me” – Kant’s Timeless Meditation on Awe and Human Dignity

- What Kant Meant by ‘Self-Imposed Immaturity’ – A Deep Dive Into the Spirit of Enlightenment”