Quote Analysis

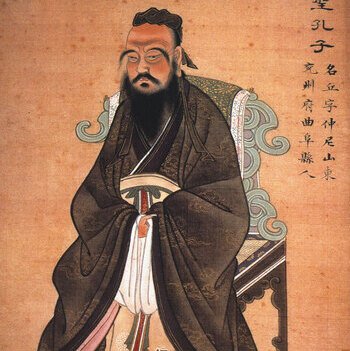

In everyday life, the hardest choices aren’t between “good” and “bad”—they’re between what feels rewarding now and what you’ll respect yourself for later. Confucius captures that tension with a sharp contrast between two ways of thinking:

“The gentleman understands what is right; the small man understands what is profitable.”

At first glance, it sounds like a moral lecture. But it’s really a practical warning about how trust collapses when every decision is reduced to personal gain—and why character matters most when no one is keeping score.

What the quote means in plain terms

Confucius is not simply dividing people into “good” and “bad.” He is describing two habits of judgment—two inner compasses that guide decisions. The “gentleman” (often translated from junzi) is the person who first asks: What is right? What is fair? What is worthy of respect? The “small man” (often linked to xiaoren) is the person who first asks: What do I gain? What helps me win right now? The action may look similar on the surface, but the motive changes everything.

Think of a workplace moment: a mistake happens and the team must explain it. One person quietly shifts blame to protect their image. That can be “profitable” because it avoids criticism. Another person says, “I missed this—here’s how I’ll fix it.” That might cost them in the short term, but it protects trust and stability. Confucius is pointing to a simple principle: societies and groups function when people treat “rightness” as the main judge, and treat “benefit” as a secondary consideration.

To make it concrete, you can test your own decision with a simple ordered list:

- If everyone acted this way, would the group become healthier or more chaotic?

- Would I still choose this if there were no reward, applause, or advantage?

- Can I defend this decision without hiding important facts?

If your answers lean toward honesty, fairness, and accountability, you’re closer to the “gentleman” mindset Confucius praises.

The “gentleman” (junzi) as character training, not social class

A key misunderstanding is to read “gentleman” as a label for someone with status, money, or polished manners. In Confucian thought, junzi is not a birthright. It is an ideal built through training. The “gentleman” is a person who strengthens character the way an athlete strengthens a muscle: with repetition, correction, and discipline. The focus is on inner quality, not public performance.

Historically, Confucius lived in a time of political fragmentation and social instability. He saw leaders who were clever but untrustworthy, and officials who chased advantage rather than responsibility. His answer was not just “be nice.” It was: build people who can hold themselves to standards even when the rules are weak. The “gentleman” becomes reliable because they are guided by principles, not by mood or opportunity.

In modern terms, this is what professional maturity looks like. A person with the “gentleman” mindset:

- Thinks long-term: they protect reputation and relationships, not just today’s win.

- Keeps promises even when it becomes inconvenient.

- Accepts fair consequences instead of searching for loopholes.

- Corrects themselves when wrong, rather than defending ego.

Notice how practical that is. It is not about being naïve or “soft.” It is about being stable. In a team, people quickly learn who is safe to trust. The junzi is the person you can rely on because their behavior doesn’t change depending on whether the moment is profitable. That consistency is exactly what creates calm, cooperation, and real authority.

The “small man” (xiaoren) and the trap of short-term profit

The “small man” in this quote is not “poor” or “uneducated.” The word points to a narrow way of thinking. It is the mindset that reduces life to immediate advantage. Confucius is warning that when profit becomes the main judge, people start treating ethics as flexible—something to adjust when convenient.

This mindset often hides behind smart-sounding excuses. For example: “It’s not illegal,” “Everyone does it,” “I had no choice,” or “It’s just business.” These phrases can be used to silence the deeper question: Is it right? The problem is not that benefit matters at all. The problem is when benefit becomes the first and loudest voice, pushing out fairness and dignity.

A modern example is office politics. Someone may “profit” by taking credit for work they didn’t do, flattering the right person, or quietly undermining a colleague. They might get promoted faster. But the long-term damage is severe:

- Trust collapses, because people feel unsafe.

- Collaboration becomes slow, because everyone protects themselves.

- The group spends energy on control instead of creativity.

- The best people leave, because the environment becomes toxic.

Confucius would say: the small-man mindset looks effective because it wins points in the short run. But it makes the social fabric fragile. Even on a personal level, it creates anxiety, because a person who lives by advantage must constantly calculate, hide, and adapt. When your identity depends on “winning,” you can’t relax. That is why this quote is not only moral—it’s psychological. A profit-first mind often trades peace for control.

Right vs. profitable: why this is really about trust and social stability

Confucius is making a structural claim: society works when people agree that certain things are non-negotiable—honesty, fairness, responsibility, basic respect. When those collapse, everything gets more expensive: relationships, business, governance, even everyday communication. You need more contracts, more monitoring, more punishment, more “systems” to replace what trust used to provide for free.

That is the hidden power of the quote. It’s not saying “never think about outcomes.” It is saying: don’t put profit above what makes human cooperation possible. In a healthy community, people still care about success, salary, and practical results. But they keep a hierarchy:

- First: Is it right? Is it fair? Does it respect others as humans, not tools?

- Second: Is it wise? Will it create long-term stability?

- Third: Is it beneficial? Does it bring a good outcome without breaking the first two?

Here’s a simple modern illustration. Imagine a company discovers a defect in a product. The “profitable” move is to hide it until forced to act. The “right” move is to admit the problem, fix it, and compensate affected customers. The second option may cost money now—but it protects credibility, prevents lawsuits, and earns loyalty. Confucius would say: the “gentleman” sees the deeper profit—trust as capital.

So the quote teaches a mature form of realism. It does not reject benefit; it reframes it. Real benefit is what you can keep without poisoning the relationships and principles that make life stable. When you make “rightness” your main compass, you don’t just become morally better—you become someone who builds environments where people can cooperate without fear. That is why Confucius believed this distinction is the difference between a functioning society and a collapsing one.

A modern lens: teams, leadership, and everyday relationships

To see why this quote still matters, imagine a group where people must rely on each other—an office team, a sports club, a family, or even a group of friends planning something together. In these settings, “profit” rarely means only money. It can mean status, comfort, approval, avoiding blame, or getting the easiest outcome. Confucius is saying that the real difference appears when pressures rise and choices have a cost.

In a workplace, for example, two people can face the same problem: a deadline is missed. One person immediately looks for the “profitable” move—protect themselves, shift responsibility, and keep their image clean. This may work once. But the team learns a lesson: “This person is not safe.” After that, colleagues share less information, stop asking for help, and cooperation becomes guarded. The group becomes slower and more anxious.

A “gentleman” response looks different: the person focuses on what keeps the group healthy. They clarify facts, accept their share of responsibility, and suggest a fix. This is not weakness—it is leadership. The group can relax because the situation is handled openly. Confucius understood that a community is not held together by clever tactics, but by predictable fairness. That is why people who choose “right” over “gain” become stabilizers: they lower the social temperature, reduce conflict, and make collaboration possible.

The psychological layer: why short-term gain often backfires

Confucius is also describing a psychological pattern. A profit-first mindset is attractive because it provides quick rewards: you avoid discomfort, win arguments, keep advantages, or get praised. But quick rewards can train the mind in the wrong direction. Once a person learns that bending principles “works,” it becomes easier to repeat it.

Here is the hidden cost: profit-first thinking makes your inner life noisy. You have to calculate constantly—what to reveal, what to hide, who to please, how to look innocent, how to stay ahead. This can create a permanent background tension. Even if you “win,” the win feels unstable because it depends on control, not on genuine respect.

By contrast, a right-first mindset simplifies the inner world. You still think strategically, but you don’t need endless mental gymnastics. Your behavior is consistent, so you don’t have to remember different stories for different people. Over time, that consistency builds what psychologists would call “trust capital”: others give you the benefit of the doubt, conflicts resolve faster, and your reputation becomes a form of quiet power.

A helpful way to teach this is an ordered list of consequences:

- Short-term profit can create long-term suspicion.

- Suspicion reduces cooperation and increases stress.

- Stress lowers performance and increases mistakes.

- Mistakes create more conflict—so the cycle repeats.

Confucius is warning: chasing advantage may feel smart, but it often produces the very instability people fear.

An important nuance: Confucius isn’t against benefit—he’s against benefit as the highest judge

If someone reads this quote as “never think about profit,” they miss the point. Confucius lived in the real world of politics, duties, family obligations, and survival. Practical outcomes matter. The key is priority: when right and profitable conflict, which one gets the final vote?

In Confucian ethics, “rightness” is the foundation because it protects the relationships that make life workable. Profit is not evil, but it becomes dangerous when it overrides fairness. A mature mind can hold both:

- Seek good outcomes.

- Refuse to break core principles to get them.

Consider a simple example: a manager can raise profits by underpaying staff or by manipulating performance metrics. That is “profitable,” but it breaks the moral structure of the workplace. People become cynical, loyalty disappears, and the company slowly rots from inside. Another manager may choose fair standards, transparent rules, and honest evaluation. The second approach might grow slower at first, but it creates stability and attracts capable people.

This is also why Confucius often connects morality to reciprocity. “Do not impose on others what you do not wish for yourself” is a practical test: if your plan would feel unjust when you are on the receiving end, then the plan is not “right,” no matter how profitable it looks.

Historical background: why this distinction mattered in Confucius’ time

Confucius was writing and teaching during a period of political instability and moral confusion (often described as the Spring and Autumn era). Authority was weakening, states were competing, and many leaders focused on tactics, alliances, and short-term advantage. In such times, cleverness can look like wisdom—because it helps you survive the next conflict. But Confucius saw the long-term consequence: when leadership becomes purely strategic, the social order turns into a battlefield of interests.

His solution was not simply “be kind.” It was to rebuild the moral spine of society through character education. If officials, leaders, and citizens trained themselves to honor duties, speak truthfully, and act with fairness, then trust could return. That trust reduces the need for constant force and control.

In Confucian thought, good government is not only about laws. It is about example. When people see leaders choosing what is right even when it is costly, they internalize the same standards. When they see leaders chasing advantage, they learn that everything is negotiable. So this quote is a political diagnosis: societies decline when “profit” becomes the only language.

Even today, you can see the same pattern in organizations and communities: when incentives reward manipulation, manipulation spreads. Confucius is teaching you to look beneath the surface—at the standard people use to justify actions.

Practical application: a simple “character check” you can use daily

To use this quote as a tool, you don’t need to become a philosopher. You can treat it like a mental filter before decisions—especially when you are tempted by convenience or when nobody is watching. The goal is not perfection. The goal is a stable direction.

Here is a teacher-style ordered list you can apply in real situations:

- Clarify the decision. What exactly am I about to do, and who will it affect?

- Name the “profit.” What is the advantage I want—money, comfort, status, avoiding blame, saving time?

- Test the “right.” Is this fair? Is it honest? Would I respect someone else for doing this?

- Predict the trust outcome. If this became known, would it increase or decrease trust in me?

- Choose the higher standard. If profit conflicts with right, treat right as the final judge.

A practical example: you could take credit for a colleague’s idea in a meeting and “profit” socially. But the right-first choice is to acknowledge the source. That small act builds a reputation for fairness, and people become more willing to share good ideas with you. Over time, that creates more success than any single stolen moment.

Confucius is teaching something very modern: the strongest advantage is being trustworthy. When you train yourself to prefer “right” over “profitable,” you don’t just become “better”—you become someone others can safely build with.

You might be interested in…

- Why “Is it not a pleasure, having learned something, to try it out at due intervals?” Still Matters — Confucius on Practice, Habit, and Real Learning

- The Meaning Behind “Is it not a pleasure, having learned something, to try it out at due intervals? Do not impose on others what you do not wish for yourself.” — Confucius on Practice and Fairness

- The Meaning Behind “In the practice of the rites, harmony is the most valuable” — What Confucius Really Meant

- What Confucius Meant by “The gentleman understands what is right; the small man understands what is profitable.”