Quote Analysis

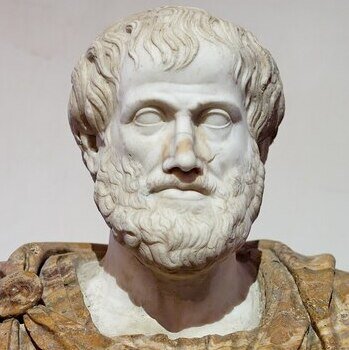

In everyday speech, “political” often sounds like party fights, elections, and endless arguments online. But Aristotle used the word in a much deeper way—closer to “life in an organized community.” That’s why his line still sparks debate today:

“Hence it is evident that the state is a creation of nature, and that man is by nature a political animal.”

He wasn’t claiming that people enjoy politics—he was explaining something stricter: that humans naturally gravitate toward shared rules, roles, justice, and a common good. So what does this famous sentence actually say about human nature, society, and the idea of living “outside” the community?

What “Political” Means in Aristotle (Not Parties, Not Elections)

When Aristotle calls a human being a “political animal,” he is not describing a hobby or an opinionated personality. He is naming a basic feature of human life: we are built to live in an organized community where people share rules, roles, and responsibilities. In Greek, the word behind “political” is tied to the polis—the city-state—so the term points to civic life, not party politics.

To understand it clearly, think of “political” as “community-shaped.” A person becomes fully human, in Aristotle’s view, not by isolating themselves, but by learning how to live with others under a framework of norms. That includes cooperation, conflict resolution, and the pursuit of what the community considers good.

An important detail is that Aristotle is not impressed by the simple fact that humans gather in groups. Many animals do that. What makes us “political” is that we argue about standards: what is fair, what is harmful, what counts as responsibility, and what should be rewarded or punished. Even if you avoid news and elections, you still act as a “political” being when you negotiate rules at work, decide how chores are shared at home, or insist that something is unjust. In other words, politics here is not noise—it is the structure of shared life.

Why Aristotle Says the State Is “Natural” (A Result of Human Nature)

The phrase “the state is a creation of nature” can sound strange today, as if Aristotle is saying government is automatic, perfect, or morally unquestionable. He is not saying that. He is making a different claim: that forming stable communities is a natural outcome of what humans are and what humans need.

Aristotle thinks human life develops through a sequence of associations. We start with the household, because basic survival requires cooperation. Households connect into villages for greater stability and division of labor. Finally, the city-state emerges as the most complete form of community, because it can support not only survival, but also law, education, and public decision-making. In short: nature pushes us toward communities that can do more than keep us alive—they can help us live well.

A teacher-friendly way to put it is this: the state is “natural” in the way language is natural. Nobody is born speaking a finished language, yet language emerges wherever humans live together because it fits our capacities and needs. Similarly, political structures emerge because humans need coordination, protection, and shared standards.

If you want to see the point in modern life, look at what happens when rules are missing. People don’t become “free”; they become vulnerable to the strongest, the loudest, or the most ruthless. Aristotle’s “natural state” is not a praise of every regime—it is a diagnosis: humans tend toward institutions because institutions make stable, shared life possible.

Logos: The Human Ability That Turns a Group into a Political Community

Aristotle’s deepest argument is not “humans live together,” but why humans live together in a special way. The key word is logos—often translated as speech, reason, or rational discourse. Animals can communicate signals (danger, food, dominance). Humans do something more advanced: we use language to discuss values and norms.

This matters because it explains why Aristotle thinks politics is inseparable from morality. A political community is not just a crowd; it is a place where people can debate and decide questions like:

- What counts as justice and injustice?

- What is beneficial for the community, and what is harmful?

- What obligations do people owe each other?

- When is punishment fair, and when is it abuse?

These are not “extra” topics. For Aristotle, they define political life itself. The city exists not only to prevent chaos, but to create a framework where people can practice virtues—fairness, courage, responsibility, moderation—because virtues require social situations to become real.

Modern examples make this easy to see. A workplace becomes “political” the moment people argue about fairness in promotions. A family becomes “political” the moment someone says, “That’s not a fair division of labor.” Even a friend group becomes “political” when it sets boundaries and expectations. Logos is what allows humans to turn daily cooperation into a shared moral world—and that is exactly why Aristotle calls us political by nature.

“Outside the Community”: Why Aristotle Says You Become a “Beast” or a “God”

This is one of Aristotle’s sharpest lines, and it’s easy to misunderstand if you read it as an insult. He is not simply mocking loners. He is making a structured philosophical point: a fully human life—one that includes moral character, justice, responsibility, and stable meaning—normally requires participation in a community with laws and shared standards.

When Aristotle says that a person outside the community is either a “beast” or a “god,” he is describing two extremes:

- The “beast” is someone who lives without law, without shared norms, and without accountability. Not necessarily an animal in the literal sense, but a person ruled mainly by impulse and force, because nothing around them trains or limits their behavior.

- The “god” is the opposite extreme: a being so self-sufficient that it needs nothing from others—no protection, no cooperation, no education, no correction. Aristotle treats this as unrealistic for ordinary humans.

Historically, think about the Greek city-state: citizenship was tied to participation in public life—courts, assemblies, military duty, shared rituals. A person who rejected that framework was not seen as “neutral,” but as disconnected from the moral environment that shapes character. Philosophically, Aristotle’s point is strict: most of us are not built to be morally complete in isolation. We learn fairness by sharing, patience by waiting, responsibility by being relied on, and justice by facing rules that apply to everyone.

Politics in Everyday Life: How You “Do Politics” Without Following Politics

Many people say, “I hate politics,” and mean they dislike parties, scandals, or ideological noise. Aristotle would answer: you can dislike the spectacle and still be political by nature—because “political” here means living through shared rules and negotiated responsibilities. The moment you live among others, you enter a world of expectations, boundaries, and judgments about what is fair.

You see this clearly in ordinary situations:

- At work: Who gets credit? How are tasks distributed? What counts as “doing your part”? These are political questions in Aristotle’s sense because they deal with fairness and order.

- In a family: Chores, money, caregiving, and rules for children all require decisions about justice and responsibility.

- Among friends: Even informal groups create norms—what is acceptable humor, what counts as loyalty, how conflict is resolved.

Notice the pattern: politics is not “debating the state,” but building a shared life. Aristotle would say that humans naturally create mini-communities everywhere—teams, households, neighborhoods—and those communities need rules to avoid chaos and resentment.

The philosophical layer is important: when you say “That’s not fair,” you are doing exactly what Aristotle highlights as uniquely human. You are not just reacting emotionally; you are appealing to a standard that others should recognize. That is the DNA of political life: disagreement handled through reasons, not only through force.

The Core Message: Community as the Condition for a Fully Human Life

If you want Aristotle’s main lesson in simple terms, it is this: humans do not only want to survive; they want to live well, and living well requires a community capable of justice, education, and shared purpose. That is why he connects the “state” with nature. He believes the highest form of human association is the one that supports virtue and the common good—not merely comfort.

Historically, Aristotle is writing in a world where the polis is the center of identity. But the deeper idea travels well into modern life. We still need institutions—schools, courts, workplaces, civic rules—because they shape behavior and protect people from pure power struggles. Where institutions collapse, you often see the return of the “strongest wins” logic. Aristotle would call that a slide toward the “beast” side of the spectrum.

Philosophically, he also gives a demanding view of freedom. Freedom is not “no rules.” Real freedom is the ability to live under reasonable rules that make a shared life possible. In that sense, community is not the enemy of the individual; it is the environment where human capacities mature.

A clear teaching takeaway is: Aristotle’s quote is not praising politics as entertainment. It is reminding you that being human includes learning to share space, negotiate norms, and aim at something beyond private desire—because that is how justice and character become real.