Quote Analysis

Curiosity is one of the few human traits that shows up everywhere—at work, in relationships, and in the quiet moments when a simple “it works” isn’t enough. We naturally push past the surface and ask why. That is exactly the impulse behind the famous line:

“ALL men by nature desire to know.”

It’s often repeated as a motivational slogan, but its original philosophical meaning is sharper: it describes a built-in drive to move from impressions to causes, from facts to explanations. In other words, the mind doesn’t stay calm when something lacks sense—it hunts for understanding.

Authorship and Context

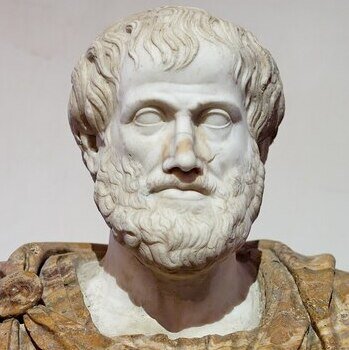

This sentence is widely quoted, but it’s important to place it correctly. Even when people attach the name “Plato,” the line is most strongly associated with Aristotle, because it functions as the opening move of his philosophical project: a claim about what drives human thinking in the first place. The key idea is not “everyone loves school” or “everyone enjoys studying.” Aristotle is pointing to something more basic: the mind tends to move from seeing to understanding. In his framework, philosophy starts when you refuse to stop at description.

Historically, this matters because Greek philosophy wasn’t built as a collection of inspirational sayings. It was built as a method: observe the world, ask what something is, then ask why it is that way. So the quote works like a doorway: it explains why humans don’t just experience reality—they interrogate it. You can see the same pattern today in ordinary life. Someone might accept “the app crashed,” but another person asks, “What triggered it? What changed?” That second reaction is exactly what this line is describing: a natural push toward explanation, not just information.

What “By Nature” Really Means

The phrase “by nature” is where many readers misunderstand the quote. It does not mean that every person is born equally knowledgeable, equally intelligent, or equally motivated to read books. “By nature” means there is a built-in tendency—a starting impulse—before training, education, or career choices. Think of it like hunger: people may eat different foods and have different habits, but the basic drive to eat is there. In the same way, Aristotle is saying that humans have a basic drive to make sense of what they encounter.

This is also why the quote does not collapse the moment you find someone who “doesn’t care about learning.” Often, the desire to know is still present, just expressed differently. People want to know what others think of them, why a relationship changed, why their body feels tired, why money keeps disappearing, why a plan failed. That is knowledge-seeking too—just not always academic.

To keep the meaning clear, it helps to separate:

- An inner impulse (wanting understanding)

- A skill (knowing how to think well)

- A habit (actually doing it consistently)

Aristotle’s claim is mainly about the first point: the impulse exists before the skill is refined.

Desire to Know vs. Simple Curiosity

Not all curiosity is the same. People can be curious about gossip, novelty, or entertainment, and that kind of curiosity can stay shallow: “What happened?” “Who said what?” “What’s the latest rumor?” Aristotle’s “desire to know” is more serious. It aims at causes, not just updates. It pushes the mind from surface facts to deeper explanations.

A teacher-like way to see the difference is to ask: What would satisfy the questioner? If a person is satisfied once they hear a quick detail, that’s curiosity in the light sense. If they keep asking until the situation makes sense as a whole, that’s closer to Aristotle’s meaning.

Here’s what the deeper “desire to know” tends to look like:

- It asks “Why is this happening?” not only “What happened?”

- It looks for patterns (what repeats) and principles (what explains)

- It tries to connect cause → effect, not just collect facts

- It cares about coherence: the story must “hold together”

Modern examples are everywhere. A person can memorize fitness tips, but another asks how sleep, hormones, training volume, and recovery interact. Someone can repeat political slogans, but another asks what incentives, institutions, and history produce those outcomes. The quote is praising the second kind of movement: from fragments to understanding.

The Role of the Senses: From Perception to Explanation

Aristotle links knowledge to the senses for a practical reason: knowledge doesn’t begin in the clouds. It begins with noticing. You see differences, you hear changes, you feel patterns—and your mind tries to organize them. The senses provide raw material; the intellect tries to turn that material into meaning.

Think of a simple example: you hear a strange noise in your car. The sound is sensory information, but the mind immediately wants more than that. It asks: Is it the engine? The brakes? Does it happen only when turning? That shift from perception to diagnosis is Aristotle’s point. The senses awaken questions, and questions push us toward explanations.

This is also where the quote becomes relevant to modern life, especially in a world overloaded with information. Many people “see” a lot—headlines, posts, charts, statistics—but understanding is not guaranteed. Sensory input (or data input) is only the first layer. The second layer is interpretation: what does it mean, what causes it, what follows from it?

A useful way to frame it is:

- Perception: I notice something.

- Attention: I focus on what seems important.

- Question: I ask what explains it.

- Understanding: I connect causes and consequences.

Aristotle’s opening line is reminding us that humans naturally try to climb this ladder—because the mind is uncomfortable with “just seeing” when it could also understand.

Knowledge vs. Memorization: The Difference That Matters

A common mistake is to treat “knowing” as the same thing as “remembering.” Aristotle’s idea points in the opposite direction: real knowledge is not a warehouse of facts, but an ability to explain. Memorization can be useful—dates, formulas, vocabulary—but by itself it doesn’t guarantee understanding. You can repeat a definition perfectly and still have no idea how to use it, test it, or connect it to anything else.

A teacher-like way to separate the two is to ask simple questions. If someone truly knows, they can do at least one of these things:

- Explain it in their own words without hiding behind copied sentences

- Give an example that fits the idea and a counterexample that does not

- Show the cause-and-effect chain (“If this changes, then that changes”)

- Predict what will happen in a new situation using the same principle

Modern life makes this difference very visible. Plenty of people “know” productivity hacks, yet cannot explain why they fail under stress. Many can list nutrition rules, yet cannot reason about how sleep, training load, and appetite interact. Aristotle’s point is that the mind seeks more than data: it wants a structure. Facts are pieces; knowledge is the ability to build a stable picture from those pieces.

Why This Line Is a Foundation of Philosophy

This quote is not famous because it sounds nice. It is famous because it states a methodological starting point: philosophy begins when you refuse to stop at the surface. In the ancient Greek world, that was a major shift. Instead of accepting myths, tradition, or authority as final answers, philosophers tried to reach reasons that can be examined and discussed. Aristotle’s opening line justifies the entire project: if humans naturally desire understanding, then asking “What is this?” and “Why is it like this?” is not a strange hobby—it is a deeply human activity.

Philosophically, the line also explains why humans create theories at all. We do it because we cannot tolerate chaos in our thinking. When events feel random, the mind searches for order. When explanations are missing, we invent them—sometimes wisely, sometimes poorly. This is why philosophy is not only about “big questions” like truth or existence. It is also about training the desire to know so it doesn’t turn into lazy certainty.

In that sense, the quote is both an invitation and a warning: the drive to know is natural, but the quality of what we accept as “knowledge” depends on how carefully we think.

Where the Quote Shows Up in Modern Life

It’s easy to treat Aristotle as distant history, but this idea is visible in everyday behavior. You see it whenever someone refuses to be satisfied with a quick answer. A child keeps asking “Why?” not to be annoying, but because the mind is trying to build a coherent model of the world. Adults do the same thing, just in more complex forms.

Here are modern places where the “desire to know” becomes obvious:

- Technology: It’s not enough that a phone works; people want to understand settings, privacy, algorithms, and why updates change behavior.

- Work systems: A team doesn’t only ask “Who made the mistake?” but “What process produced the mistake?”

- Relationships: People want to understand patterns—why conflict repeats, why trust breaks, why silence feels threatening.

- Health: Many move beyond “What should I eat?” to “What mechanism links sleep, stress, and appetite?”

Notice the deeper pattern: knowledge-seeking becomes most intense when consequences matter. When a system affects your life, you stop accepting slogans and start demanding explanations. In this way, the quote is not about academic ambition. It describes a practical human reaction to reality: when something matters, we want reasons, not just results.

The Risk: When the Desire to Know Becomes Bad Explanations

The drive to know is powerful, but it has a weakness: the mind often prefers any explanation over no explanation. That’s why Aristotle’s line can be read as a warning about human psychology. When people don’t have solid understanding, they may grab the first story that feels satisfying—especially if it reduces anxiety or gives a clear enemy, a simple cause, or a comforting certainty.

This is how the desire to know can slip into poor thinking:

- Oversimplification: Complex systems get reduced to one cause (“It’s always X”).

- Confirmation bias: People search only for evidence that supports what they already believe.

- False certainty: A confident story is accepted as truth, even without support.

- Conspiracy thinking: Randomness is reinterpreted as hidden intention because intention feels more “explainable.”

A modern example is how people consume information online. They see a headline, feel confusion or anger, and then accept a neat explanation that matches their emotions. The desire to know is real—but the method is weak. The philosophical lesson is clear: the urge for understanding is natural, yet it must be disciplined. Good knowledge doesn’t just calm you down; it can survive questions, evidence, and alternative explanations. That is the difference between a mind that merely wants to know and a mind that is actually learning to know well.