Quote Analysis

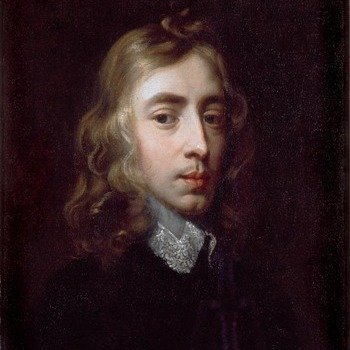

When John Milton wrote Areopagitica in 1644, he wasn’t merely challenging censorship — he was defining the moral foundation of intellectual freedom. His powerful words:

“Give me the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties.”

This quote remains powerful even after centuries. In a world where information can be controlled and opinions suppressed, Milton reminds us that true liberty begins in the mind. But what exactly did he mean by “liberty of conscience,” and why does it remain the cornerstone of democratic thought today?

The Meaning and Context of Milton’s Words

John Milton’s statement, “Give me the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties,” appears in his famous 1644 speech Areopagitica, written as a protest against government censorship in England. At that time, every printed work required approval from state authorities before publication. Milton, a devout Christian and humanist scholar, argued that such control over ideas was not only politically oppressive but also spiritually destructive.

To understand his words, imagine living in a world where every book, article, or thought had to be “approved” before being shared. Milton saw this as a direct attack on human dignity. For him, liberty was not limited to political independence or physical freedom; it was the ability to search for truth without fear. His call for liberty “to know, to utter, and to argue” is a sequence of intellectual steps: first to learn, then to speak, and finally to engage in reasoned debate. Each step depends on the previous one, forming a complete vision of mental and moral freedom.

Even today, his words echo whenever societies debate the limits of free speech, the dangers of misinformation, or the ethics of online censorship. Milton’s core message remains timeless: without the freedom to think and express, no other liberty can truly survive.

Freedom According to Milton

For Milton, freedom was not simply the absence of external control; it was the active pursuit of truth guided by conscience. He viewed the human mind as the highest gift of creation — something meant to explore, question, and grow. True liberty, therefore, was intellectual and moral, not just political. A person could live in a “free” nation yet remain enslaved by fear, ignorance, or blind obedience.

Milton’s understanding of freedom was deeply moral. He believed that liberty without conscience easily turns into chaos, while conscience without liberty turns into tyranny. In this sense, freedom was both a right and a responsibility. One had to use it wisely — not to deceive or harm, but to seek understanding and promote virtue.

To illustrate, consider a modern classroom or a democratic society. When students are encouraged to ask difficult questions, discuss ideas openly, and form their own conclusions, they practice the very freedom Milton defended. However, when they repeat opinions without reflection or silence themselves out of fear, liberty loses its meaning.

Milton teaches that freedom of thought is sacred because it is the foundation of every other form of progress — scientific, political, and moral. Without it, knowledge becomes dogma, and truth fades into mere authority.

The Role of Knowledge, Speech, and Debate

Milton’s triad — to know, to utter, and to argue — forms the intellectual foundation of his idea of liberty. These are not random verbs; they represent a natural sequence of how human understanding grows. First, one must know — seek knowledge through study, observation, and reason. Knowledge gives the mind substance and direction. Second, one must utter — express what has been learned, share it with others, and contribute to the collective conversation. Finally, one must argue — test ideas through rational dialogue and disagreement, refining truth through exchange.

This process mirrors the way science, philosophy, and even democracy evolve: through open questioning and debate. Milton believed that truth does not need protection from error; it emerges stronger when challenged. In his time, censorship aimed to prevent falsehoods from spreading, but Milton saw that as dangerous. Shielding people from wrong ideas also shields them from the opportunity to learn and discern truth themselves.

In modern terms, think of a classroom, social media, or a public forum. When discussion is open, even controversial, it leads to intellectual growth. When it is silenced, people become passive and uncritical. Milton’s insight reminds us that knowledge without dialogue becomes sterile, while speech without knowledge becomes empty noise. Only their balance — knowing, speaking, and debating — sustains a healthy and free society.

Conscience as the Moral Compass

In Milton’s philosophy, conscience is the highest guide of human behavior — the inner voice that tells us not merely what we can do, but what we ought to do. Freedom of speech, therefore, is not meant to excuse recklessness or manipulation; it is bound by moral responsibility. Milton insisted that liberty must serve truth and virtue, not selfish interest or malice.

He viewed conscience as a divine faculty — a connection between human reason and moral truth. To act “according to conscience” means aligning our freedom with ethical awareness. In this sense, liberty and conscience are inseparable: without conscience, freedom becomes destructive; without freedom, conscience becomes meaningless.

For example, in public discourse today, the right to express an opinion must be tempered by honesty and respect for others. Freedom of the press, for instance, is valuable only when it seeks to inform, not to deceive. Likewise, a scientist must publish results truthfully, not to gain fame but to serve knowledge.

Milton’s view is strikingly modern: he anticipated the ethical dilemmas we face in an age of mass communication. His message to students and thinkers alike is simple yet profound — freedom without conscience is chaos, but conscience without freedom is silence. True wisdom lives in the harmony between the two.

The Connection Between Milton’s Ideas and Modern Democracy

Milton’s defense of intellectual freedom in Areopagitica laid one of the earliest philosophical foundations for modern democracy. He believed that a just society depends on the ability of its citizens to think, question, and speak freely. Without these abilities, even the most advanced political institutions risk becoming oppressive. In his view, truth and liberty sustain each other — when one weakens, the other soon follows.

This idea strongly influenced later democratic thinkers such as John Locke, Thomas Jefferson, and John Stuart Mill. The principle that free discussion is essential to progress became central to the Enlightenment and later to constitutional democracies. Today, we can see Milton’s legacy in every constitution that protects freedom of speech and press.

For example, debates in universities, the existence of investigative journalism, and public protests all reflect Milton’s conviction that an open exchange of ideas keeps power accountable. However, his message also carries a warning: democracy fails when people stop engaging critically. Freedom of expression must be nurtured through education, respect for truth, and civic participation — otherwise, it decays into noise and manipulation. Milton reminds us that democracy is not sustained by authority, but by active and thoughtful minds.

Truth as a Process, Not a Possession

Milton’s philosophy suggests that truth is not something owned, but something discovered through open reasoning. He rejected the notion that any single person or institution could claim absolute truth. Instead, he saw truth as dynamic — an ever-evolving understanding shaped by discussion, reflection, and moral inquiry.

This perspective aligns with what we call the philosophy of inquiry, found later in the works of thinkers like Mill and Dewey. It emphasizes that error and disagreement are not enemies of truth but its necessary companions. For Milton, suppressing false opinions was not the way to protect truth; rather, it was through confronting them that truth becomes clearer and stronger.

In practical terms, this means that censorship, even when well-intentioned, harms the search for understanding. A student learns best not by memorizing conclusions, but by testing them through evidence and logic. Similarly, societies advance when they allow different voices to challenge prevailing beliefs.

Philosophically, Milton’s approach recognizes the humility of knowledge — we never fully possess the truth; we approach it. His vision invites us to see truth as a journey shared by all rational beings, not as a trophy held by a few.

The Mind’s Freedom as the Highest Form of Liberty

Milton ends his argument by elevating the freedom of the mind above all other liberties. Physical freedom, property, or political rights lose meaning if the human mind is enslaved by ignorance or fear. To be truly free, one must be able to think independently, guided by conscience and reason. This is the liberty “above all liberties” that Milton cherished.

In this view, freedom of thought is not a privilege but the very essence of human dignity. When external powers — governments, institutions, or social pressures — dictate what we may believe, they diminish our humanity. Milton’s warning remains urgent even today, in an age where technology can shape opinions and limit perspective.

To illustrate, imagine a society where citizens are free to travel or vote, but not to question their leaders. Such a society, Milton would argue, is not truly free. The highest liberty lies in mental independence — the ability to examine, doubt, and seek truth on one’s own terms.

For students and thinkers, this means cultivating intellectual courage:

- To question accepted norms.

- To listen, but not blindly follow.

- To defend reason even when it is unpopular.

Milton’s legacy teaches that the freedom of the mind is not only the root of all progress but also the soul of moral and spiritual life itself.

You might be interested in…

- “Better to Reign in Hell, Than Serve in Heaven” – The Tragic Meaning Behind Milton’s Famous Line

- “He Who Reigns Within Himself” – John Milton’s Timeless Lesson on Self-Mastery and Inner Freedom

- “Give Me the Liberty to Know, to Utter, and to Argue Freely” – John Milton’s Timeless Defense of Free Thought

- “The Mind Is Its Own Place” – What John Milton Really Meant About Heaven and Hell Within Us

- “Long is the Way and Hard, That Out of Hell Leads Up to Light” – The Deeper Meaning Behind Milton’s Vision of Redemption