Quote Analysis

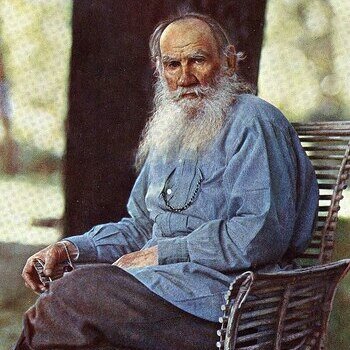

True happiness often feels like something we must chase—through success, wealth, or approval. Yet Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy reminds us of a different truth:

“Happiness does not depend on outward things, but on the way we see them.”

This timeless idea invites us to rethink how we define joy and fulfillment. Instead of trying to control life’s circumstances, Tolstoy challenges us to master our perception. Could it be that peace and contentment are not found in the world around us, but in the lens through which we view it?

The Inner Philosophy of Happiness in Tolstoy’s Thought

When Tolstoy speaks about happiness not depending on “outward things,” he challenges one of the most persistent human illusions — the idea that joy is something we can achieve through possessions, status, or control. His philosophy invites us to look inward, to examine how our mind shapes reality. Tolstoy himself experienced this deeply: despite fame and wealth, he often felt spiritually empty until he embraced a simpler, more mindful life.

From a philosophical point of view, Tolstoy’s message aligns with the ancient idea that our emotions follow our thoughts, not our circumstances. The same event can make one person miserable and another grateful — the difference lies in perception. This insight anticipates what modern psychology now calls cognitive reframing, the ability to change one’s emotional state by interpreting experiences differently.

For example, losing a job might appear disastrous to one person but liberating to another who sees it as a chance to grow. Tolstoy’s lesson, then, is that happiness is not a gift from life but a skill — a way of seeing, cultivated through awareness, gratitude, and moral clarity.

Understanding the Meaning of the Quote

The essence of Tolstoy’s quote lies in its contrast between external conditions and inner perception. When he says that happiness “does not depend on outward things,” he reminds us that material comfort or social recognition offer only temporary satisfaction. The second part — “but on the way we see them” — shifts responsibility to the individual. Our worldview, not the world itself, determines how peaceful or restless we feel.

To understand this more clearly, think of two people walking in the rain. One complains about the weather, while the other enjoys the freshness of the air and the sound of raindrops. The situation is identical, yet their experiences differ completely because of their interpretation. Tolstoy uses this logic to explain that we cannot control events, but we can control our attitude toward them.

This idea also reflects his moral teaching: lasting joy comes from humility, compassion, and acceptance rather than desire or ambition. In today’s fast, comparison-driven society, Tolstoy’s insight feels revolutionary — reminding us that the power to feel content lies not in changing the world, but in changing how we see it.

The Psychological and Philosophical Dimension

Tolstoy’s idea that happiness depends on perception rather than possessions touches both philosophy and psychology in profound ways. Philosophically, this statement echoes the Stoic belief that human beings cannot control the world, but they can control their judgment of it. For the Stoics, freedom begins when one stops being enslaved by emotions triggered by external events. Tolstoy, although coming from a Christian and moral perspective, arrives at a similar conclusion: peace is not achieved by altering life’s conditions but by mastering the mind that interprets them.

From a psychological standpoint, Tolstoy’s insight foreshadows what modern cognitive-behavioral therapy teaches — that our thoughts shape our emotions. When we choose to interpret a challenge as an opportunity instead of a failure, our emotional state transforms instantly. Tolstoy understood this intuitively long before psychology gave it scientific form.

Imagine a person stuck in traffic. A mind ruled by irritation sees wasted time; a calm, self-aware mind sees a rare pause to breathe and reflect. This contrast reveals the core of Tolstoy’s message: happiness is not a product of what happens to us, but of what happens within us. Learning to reshape perception, therefore, becomes both a philosophical discipline and a psychological exercise in freedom.

The Ethics of Gratitude and Simplicity

Tolstoy’s view of happiness is inseparable from his moral philosophy — a life guided by gratitude, humility, and simplicity. He believed that when we constantly crave more, we enslave ourselves to dissatisfaction. The antidote is gratitude: the conscious recognition of what is already good, however small. In Tolstoy’s later years, after renouncing his aristocratic comforts, he found joy in labor, nature, and human connection. His transformation was not ascetic pride but an ethical awakening — a realization that true contentment requires moral balance, not abundance.

This ethical layer is crucial because it connects inner peace with moral responsibility. Gratitude teaches us to see blessings rather than lacks; simplicity liberates us from endless wanting. For students of philosophy, it’s important to see how Tolstoy links happiness with moral character — a happy person is not one who owns more, but one who desires less.

In modern life, where consumerism equates happiness with consumption, Tolstoy’s lesson is radically countercultural. He reminds us that serenity grows not from accumulation, but from appreciation. Practicing gratitude daily — pausing to value a meal, a friendship, or even silence — is Tolstoy’s practical path to enduring happiness.

A Parallel with the Modern World

In the modern era, Tolstoy’s message feels almost revolutionary. We live in a culture that constantly measures happiness by external markers — income, appearance, popularity, or digital validation. Social media, for instance, amplifies the illusion that joy comes from comparison or public approval. Yet, as Tolstoy reminds us, this pursuit often leads to emptiness, because the goal keeps moving. The more we chase, the more dissatisfied we become.

Tolstoy’s wisdom invites us to pause and reexamine our relationship with success. He teaches that peace of mind cannot exist in a life that depends on external applause. In practical terms, this means learning to find satisfaction in quiet achievements — acts of kindness, personal growth, or meaningful work — rather than visible trophies.

Modern psychology supports this timeless truth. Studies in positive psychology reveal that happiness is closely linked to internal attitudes like gratitude, purpose, and self-compassion, not to wealth or fame. When Tolstoy wrote, “If you look for perfection, you’ll never be content,” he captured the very essence of our contemporary dilemma: perfectionism prevents joy. His words urge us to accept imperfection as part of life’s beauty and to recognize that fulfillment grows when we stop measuring ourselves by external standards.

Tolstoy’s philosophy, therefore, serves as a bridge between past and present — a moral compass for navigating the noise of modern living. It encourages students, thinkers, and ordinary readers alike to seek balance between ambition and inner calm.

The View That Creates Happiness

The ultimate lesson Tolstoy leaves us with is that happiness is not found but created. It is an inner craft, developed through awareness and deliberate choice. To “see things rightly,” as he implies, requires training of the mind — just as we train the body or a musical skill. This means becoming conscious of how we interpret experiences and learning to shift from complaint to appreciation.

For example, when faced with hardship, instead of asking “Why me?”, Tolstoy would encourage asking, “What can this teach me?” That change of perspective turns adversity into a teacher, not an enemy. The key lies in recognizing that the mind filters reality: we cannot always change events, but we can always shape our response.

Philosophically, this outlook reflects Tolstoy’s lifelong search for moral and spiritual clarity. After years of inner struggle, he realized that happiness is not the absence of pain, but the presence of understanding. The “way we see things” becomes a mirror of the soul — clear perception leads to peace; distorted perception leads to suffering.

In practical education, this means helping students develop the habit of mindful observation: to notice how thoughts color emotions, and how gratitude transforms perception. Tolstoy’s wisdom thus becomes not just literature, but a guide to living — an invitation to see the world not as it appears, but as it could be, when viewed through the eyes of peace.

You might be interested in…

- The Hidden Truth Behind Tolstoy’s “If You Look for Perfection, You’ll Never Be Content”

- The True Meaning Behind Tolstoy’s Words: “There is No Greatness Where There Is Not Simplicity, Goodness, and Truth”

- “Everyone Thinks of Changing the World, But No One Thinks of Changing Himself” – Tolstoy’s Timeless Lesson on Inner Revolution

- “The Two Most Powerful Warriors Are Patience and Time” – Tolstoy’s Timeless Lesson on Inner Strength

- “Happiness Does Not Depend on Outward Things” – What Tolstoy Really Meant About Inner Peace