Quote Analysis

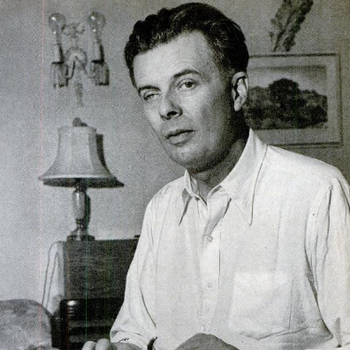

Solitude has often been misunderstood as isolation or weakness, yet for thinkers, writers, and visionaries it has been the very soil in which creativity flourishes. Aldous Huxley captured this truth when he wrote:

“The more powerful and original a mind, the more it will incline towards the religion of solitude.”

With these words, Huxley highlights the paradox of intellectual life: the strongest and most authentic minds are often those that seek silence, reflection, and distance from the crowd. But why does solitude matter so much for originality, and what can we learn from this perspective today?

Introduction to Huxley’s Quote

When Aldous Huxley declared, “The more powerful and original a mind, the more it will incline towards the religion of solitude,” he was not making a casual observation, but pointing to a recurring truth in intellectual history. To understand his words, it is useful to pause and ask: why would solitude become a natural choice for a creative or independent thinker? The answer lies in the demands of originality. To think in ways that are new, to challenge conventions, or to form deep insights requires mental space free from constant noise and distraction.

Consider great figures such as Isaac Newton, who formulated groundbreaking theories while working in isolation during the plague, or Virginia Woolf, who emphasized the necessity of “a room of one’s own” for any writer. Their achievements were not accidents of genius alone; they were nurtured by periods of silence and separation from the crowd. In solitude, a mind is not pressured to conform, and this freedom opens pathways to creativity and deeper understanding.

Seen in this way, Huxley’s words remind us that solitude is not merely the absence of others. It becomes a deliberate environment—almost a discipline—that allows thought to expand beyond the ordinary. This is why he likens it to a “religion”: something revered, practiced, and essential for a higher kind of life.

Power and Originality of the Mind

The phrase “powerful and original mind” can be unpacked on several levels. A powerful mind is not only one that possesses high intelligence, but one that demonstrates clarity, persistence, and the courage to question prevailing beliefs. Originality, on the other hand, refers to the ability to think in ways that are not borrowed or imitative, but rooted in independent reflection. Together, these qualities often set an individual apart from the crowd.

Historically, we can see this in philosophers such as Søren Kierkegaard, who chose to live in deliberate separation from society in order to challenge religious and cultural assumptions of his time. Similarly, artists like Vincent van Gogh, though often misunderstood in his life, relied on solitude as the backdrop for creating works that broke away from artistic norms. Their inclination toward withdrawal was not a weakness, but a condition for producing something authentic.

In modern terms, think of innovators in technology or science who need “deep work” environments, free from interruptions, in order to solve complex problems. The pattern repeats: when the mind is both strong and original, it often resists shallow distractions and seeks depth instead. This tendency can make solitude appear not as an escape, but as a necessity. Huxley’s insight, then, is not just about temperament—it is about the conditions under which true intellectual and creative breakthroughs emerge.

The Religion of Solitude – Understanding the Metaphor

When Huxley speaks of a “religion of solitude,” the wording is carefully chosen. Religion here does not mean formal rituals or organized belief systems, but a disciplined way of life, something that shapes values and gives meaning. By using this metaphor, Huxley suggests that solitude is not an accidental state but a practice, almost like a spiritual devotion, embraced by those who wish to preserve the integrity of their own minds.

Throughout history, we find examples of thinkers and mystics who treated solitude as sacred. Monks in Christian monasteries, Buddhist hermits in the mountains, or poets like Rainer Maria Rilke all considered solitude a source of inner clarity. For them, it was a path to truth that no collective conversation could provide. In their eyes, solitude was not about turning away from the world permanently, but about retreating long enough to return with deeper insight.

In modern life, the metaphor still makes sense. Consider writers who set aside hours every morning to work in silence, or scientists who close themselves off in laboratories to pursue experiments. The consistency of the practice mirrors religious devotion: it requires patience, repetition, and trust in the process. Thus, Huxley’s phrase reminds us that solitude is not simply being alone—it is a form of commitment that nurtures creativity and original thought.

Solitude versus Loneliness

It is important to make a clear distinction between solitude and loneliness, because they are often confused. Solitude is the chosen act of being alone for the sake of reflection, creation, or inner peace. Loneliness, on the other hand, is an unwanted state of isolation, often accompanied by sadness or a sense of disconnection from others. Understanding this difference helps us see why Huxley speaks of solitude as a strength rather than a weakness.

To illustrate, imagine an artist who spends a weekend alone in a cabin to finish a painting. This is solitude: the absence of distractions makes the work possible. Now compare that to someone in a crowded city who feels invisible and longs for connection—this is loneliness. The external conditions may look similar, but the inner experience is completely different.

Philosophers such as Nietzsche emphasized that solitude could be empowering, giving one space to “become who you are.” Psychologists today echo this, noting that deliberate solitude can reduce stress, improve concentration, and increase creativity. By contrast, chronic loneliness is linked to anxiety, depression, and even physical illness.

For students, the lesson is clear: solitude is a tool when it is intentional and purposeful, while loneliness is a condition to be addressed. Recognizing the boundary between the two allows us to cultivate solitude as a positive force, while seeking support and connection when isolation becomes harmful.

Historical Figures and Solitude

To understand why Huxley valued solitude so highly, it helps to look at the lives of those who practiced it before him. History is filled with examples of thinkers, scientists, and artists who consciously withdrew from society to deepen their work. Consider Blaise Pascal, who stepped away from the distractions of Parisian life to produce his Pensées. Nikola Tesla often worked through the night in isolation, developing ideas that transformed modern technology. Emily Dickinson lived a reclusive life, but her poetry reveals a depth of perception that could hardly have been achieved without long hours of quiet reflection.

In today’s context, innovators in technology and science still follow a similar pattern. Programmers, researchers, and novelists often rely on uninterrupted time alone to nurture ideas. What ties them to their predecessors is the recognition that solitude is not retreat, but the condition under which original thought can thrive.

Ethical and Existential Lessons

Huxley’s statement is not only a description of intellectual life; it also carries ethical and existential lessons for modern readers. At its core, the “religion of solitude” teaches us that withdrawing from the crowd can be a way of preserving authenticity. When we constantly mirror others’ expectations, our decisions become shaped by conformity rather than by truth. By stepping back into solitude, we reclaim the ability to think and act from our own principles.

This has strong ethical implications. For example, a scientist pressured by industry or politics may be tempted to ignore uncomfortable results. Yet as Huxley reminded us, “Facts do not cease to exist because they are ignored.” Solitude, in this sense, provides the moral space to resist external pressures and to remain faithful to truth.

Existentially, solitude helps us confront ourselves. It is in moments of silence that people ask questions about meaning, mortality, and purpose. Think of Søren Kierkegaard, who believed that solitude was necessary for the individual to encounter God, or Jean-Paul Sartre, who saw isolation as the setting in which freedom reveals itself. In both views, solitude forces us to grapple with the fundamental realities of life.

For students and modern professionals alike, the lesson is clear: solitude is not a luxury but a responsibility. It is a practice that grounds us ethically, strengthens our sense of authenticity, and helps us face the questions that truly matter.

You might be interested in…

- “Maybe This World Is Another Planet’s Hell” – Aldous Huxley’s Dark Reflection on Human Existence

- “After Silence, That Which Comes Nearest to Expressing the Inexpressible Is Music” – Aldous Huxley’s Reflection on Art Beyond Words

- “The More Powerful and Original a Mind” – Aldous Huxley on the Religion of Solitude

- “Facts Do Not Cease to Exist Because They Are Ignored” – Aldous Huxley’s Warning About Truth and Responsibility

- “Words Can Be Like X-Rays” – Aldous Huxley on the Transformative Power of Language