Quote Analysis

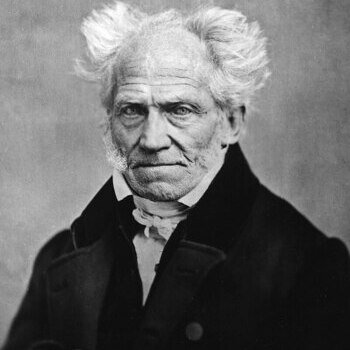

When Arthur Schopenhauer declared:

“Man can do what he wills but he cannot will what he wills,”

he captured in one sentence a profound tension between human freedom and hidden forces that shape our desires. At first glance, it seems we are free to act on our choices. But are we truly free if the very source of our choices—our will—is beyond our control? This paradox raises deep questions about responsibility, morality, and the nature of human existence. In this article, we will explore what Schopenhauer really meant and why his insight still resonates today.

Introduction to Schopenhauer’s Philosophy

Arthur Schopenhauer was one of the most influential philosophers of the 19th century, and his thinking revolves around a central concept: the will. Unlike many thinkers before him, who placed reason at the heart of human identity, Schopenhauer argued that reason is only secondary. Beneath all of our rational explanations lies a deeper, blind force—what he called the “will to live.” This will is not something we consciously choose; rather, it drives us, shapes our instincts, and influences our decisions in ways we often do not recognize.

To understand this, imagine a student who claims he decided to become a doctor because it is a noble profession. Schopenhauer would say that this reasoning is only the surface explanation. The true driving force might be a deep, unconscious desire for security, status, or survival, all of which arise from the will. By framing human life in this way, Schopenhauer introduced a radical idea: human beings are not as rational and autonomous as they believe. Instead, we are pushed and pulled by forces that precede conscious thought. This perspective not only challenges the Enlightenment view of human freedom but also anticipates modern psychology’s recognition of unconscious drives.

The Meaning of the Quote: Freedom and the Limits of Will

The famous line, “Man can do what he wills but he cannot will what he wills,” is Schopenhauer’s concise way of describing the limits of human freedom. On the surface, it looks like we are free because we can carry out our desires. For example, if I want to raise my hand right now, I can do so without any external obstacle. That seems like freedom. But Schopenhauer insists that the real question goes deeper: why did I want to raise my hand in the first place? That initial impulse, that desire, is not something I consciously created—it simply appeared within me.

This means that human beings are free only in a very restricted sense. We can act according to our will, but we cannot control the origin of that will. In practical terms, consider how people make life choices: one person feels drawn to art, another to mathematics, and another to leadership. None of them chose their fundamental inclinations; they were given by temperament, upbringing, or inner drives. Schopenhauer argues that this shows our freedom is more illusion than reality. We are not masters of our desires, only executors of them. This challenges the optimistic view of free will found in many philosophical and religious traditions, and it forces us to rethink concepts like responsibility and moral agency.

The Will as a Blind Force of Life

For Schopenhauer, the will is not a rational plan or a carefully constructed idea. It is an underlying force that drives every living being to act, often without clear awareness or reason. He described it as “blind” because it does not operate with foresight or purpose—it simply pushes life forward. Think of hunger: when you feel it, you are compelled to eat, not because you made a conscious philosophical decision about nutrition, but because the will, expressed through your body, demands satisfaction.

This notion extends far beyond basic instincts. Our ambitions, longings, and even passions can be traced back to the will. A person who feels a constant urge to compete, another who is drawn toward love, or someone obsessed with creative expression—all are manifestations of this deeper drive. Schopenhauer argued that this explains why people often feel restless: as soon as one desire is fulfilled, another quickly arises, keeping us in an endless cycle of striving.

To grasp this better, compare it to a river current. The current pushes forward regardless of whether the individual waves on the surface move smoothly or chaotically. Human actions and choices are like those surface waves, while the will itself is the unstoppable current underneath. Understanding this image helps us see why Schopenhauer considered freedom an illusion: the current of the will dictates the general flow of our lives.

Philosophical Implications: Determinism and the Illusion of Freedom

The implications of Schopenhauer’s idea are profound. If our will is beyond our control, then human freedom seems to shrink dramatically. This position places him in line with determinism—the belief that every event, including human choices, is the result of prior causes. Just as a falling apple follows the laws of gravity, our decisions follow the dictates of the will combined with external circumstances.

Yet Schopenhauer’s determinism is unique. He does not say that external conditions alone shape us, as some materialists did. Instead, he emphasizes the role of inner necessity: the will itself is the ultimate lawgiver. For instance, a person may choose to become a writer because they “love words,” but the love of words itself is not something they freely selected—it arose from their nature and experiences.

This outlook has far-reaching consequences. If our desires are given rather than chosen, then concepts like moral responsibility or guilt must be reconsidered. Are we truly blameworthy for impulses that originate beyond our control? Modern neuroscience seems to echo Schopenhauer here, showing that brain activity often precedes conscious decision-making.

At the same time, some philosophers argue that recognizing these limits does not destroy all notions of freedom but reframes them. Perhaps freedom lies not in choosing desires but in how we respond to them—whether we act blindly or reflect with awareness. In this way, Schopenhauer’s challenge forces us to think critically about what it really means to be free.

Similar Philosophical Thoughts and Comparisons

Schopenhauer’s claim about the limits of will did not appear in isolation. He stood within a long tradition of thinkers questioning the nature of freedom. One of the clearest parallels is with Baruch Spinoza, who argued that people believe themselves free because they are aware of their desires but not the causes behind them. For Spinoza, as for Schopenhauer, freedom is mostly an illusion, since every desire is shaped by necessity.

On the other hand, existentialist thinkers like Jean-Paul Sartre pushed back against such determinism. Sartre believed that even though we are born into certain conditions, we are always responsible for how we interpret and respond to them. This creates a sharp contrast: for Schopenhauer, we cannot escape the dictates of will, while for Sartre, we are “condemned to be free.”

To understand the depth of Schopenhauer’s view, it helps to recall another of his central ideas: “The world is my representation”. This means that reality is always filtered through the lens of our perception and desires. When connected to the question of freedom, it implies that our very picture of the world is already shaped by forces we do not control. Thus, the debate is not just about action but about the way reality itself appears to us.

Ethics and Everyday Life: What This Quote Means for Us

Schopenhauer’s insight is not simply abstract philosophy; it raises practical questions about how we live and judge one another. If desires are not chosen, what does this mean for responsibility? In a classroom, a teacher might notice one student who is always restless and another who is calm. Schopenhauer would say that this difference cannot be reduced to mere “bad behavior” or “good character.” Instead, each student is guided by an underlying will they did not select.

This way of thinking challenges common moral assumptions. In everyday life, we often judge people harshly for their impulses: someone who craves wealth, recognition, or pleasure might be seen as selfish. But if those desires arise from a will beyond conscious choice, perhaps moral evaluation should focus less on blaming and more on understanding.

That does not mean Schopenhauer excused all behavior. He recognized that society must hold people accountable for their actions. Yet his philosophy invites us to see responsibility differently: we may not be guilty for our desires, but we are still responsible for how we manage them. For instance, someone with a quick temper cannot simply say, “It’s my will,” but must learn ways to control harmful expressions of it. This creates a space for ethics, not as punishment for desire, but as guidance for action.

The Relevance of Schopenhauer’s Thought Today

Even though Schopenhauer wrote in the 19th century, his reflections remain surprisingly relevant. In modern debates about neuroscience and psychology, scientists often show that our brains prepare for decisions before we become aware of them. This echoes Schopenhauer’s conviction that we cannot will what we will. The philosophical challenge he presented still resonates: if freedom is not absolute, how should we understand ourselves?

This perspective can be unsettling, because it removes the comforting belief that we are the sole authors of our lives. Yet it can also bring clarity. By recognizing the hidden power of will, we gain humility about our choices and compassion toward others. Instead of assuming everyone could simply “choose differently,” we learn to see the complexity of inner drives.

You might be interested in…

- The Limits of Vision in Schopenhauer’s Philosophy – What He Meant by ‘Every man takes the limits of his own field of vision for the limits of the world’

- “The Person Who Writes for Fools Is Always Sure of a Large Audience” – Schopenhauer’s Sharp Critique of Mass Culture

- “Compassion Is the Basis of Morality” – Schopenhauer’s Radical View on Ethics

- “Man Can Do What He Wills but He Cannot Will What He Wills” – Schopenhauer’s Challenge to Free Will

- “The World Is My Representation” – Understanding Schopenhauer’s Radical View of Reality