Quote Analysis

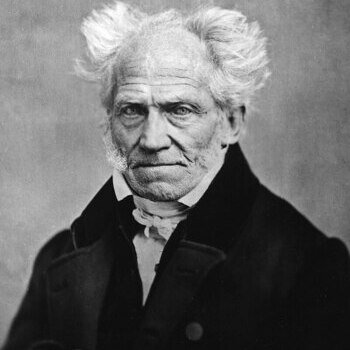

When we talk about the foundations of morality, most people think of rules, laws, or rational principles. But the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer challenged this idea in a profound way. He argued that morality is not grounded in reason or abstract concepts, but in something deeply human: compassion. As he put it:

“Compassion is the basis of morality.”

With these words, Schopenhauer claimed that true ethical behavior comes from the ability to feel another’s suffering as one’s own. But why did he see compassion as more fundamental than reason, and what does this mean for us today?

Introduction to Schopenhauer’s Thought

Arthur Schopenhauer was one of the most influential philosophers of the 19th century, often remembered for his pessimistic outlook on life. Yet, within this seemingly dark philosophy, he offered a surprisingly humane and compassionate vision of morality. To understand his statement “Compassion is the basis of morality,” we need to place it within his larger critique of other moral theories. Think of philosophers like Immanuel Kant, who believed morality was rooted in reason and duty, or utilitarians like Jeremy Bentham, who emphasized maximizing happiness.

Schopenhauer rejected both of these paths. He argued that rules and rational calculations are too detached from real human experience. Instead, he claimed that morality begins when a person genuinely feels another’s suffering and responds to it. Imagine a situation where someone sees a child in pain: according to Schopenhauer, it is not reason or duty that moves us, but the spontaneous feeling of compassion. This perspective places empathy at the very core of ethical life, offering an alternative to cold rationalism and utilitarian mathematics.

Why Compassion Instead of Reason or Interest?

Schopenhauer’s choice of compassion over reason or self-interest is not accidental. He believed that reason can justify almost anything if it serves a particular goal, and that self-interest often hides beneath a mask of morality. For example, a politician may argue for policies that appear moral but are, in reality, designed to gain votes. In contrast, compassion cannot be faked so easily—it arises when we directly identify with another’s pain.

Schopenhauer saw this as a more reliable source of moral action, because it bridges the gap between “self” and “other.” Unlike utilitarianism, which asks us to calculate pleasure and pain in abstract terms, compassion requires no calculation. It works immediately, prompting us to help without thinking of personal gain. Consider modern examples: people who donate to disaster relief efforts, or those who rescue animals from abuse, often act without rational deliberation. Their actions spring from an intuitive sense of shared humanity.

Schopenhauer believed that this direct, emotional connection provides a stronger and more authentic foundation for morality than either rational duty or pursuit of interest ever could.

Compassion as a Bridge Between Self and Other

When Schopenhauer speaks of compassion, he is not describing a vague sense of kindness or politeness. He is pointing to a profound psychological process: the ability to break down the rigid barrier between “me” and “the other.” In ordinary life, we tend to perceive ourselves as separate individuals, each with our own goals and concerns. Schopenhauer’s insight is that compassion dissolves this boundary. In moments of genuine empathy, another person’s pain feels almost as if it were our own. This is why, for example, when we see a stranger injured on the street, we may instinctively rush to help before even thinking about possible risks.

From a philosophical standpoint, this bridging function of compassion undermines radical individualism. It shows that morality does not rest on abstract duties or calculated benefits but on a lived recognition of shared vulnerability. Modern psychology supports this idea: mirror neurons and studies on emotional contagion reveal that humans are wired to resonate with each other’s feelings. In practical terms, compassion pushes us beyond self-interest. It encourages solidarity in times of crisis, cooperation in diverse communities, and even movements for social justice. By highlighting this bridge, Schopenhauer reminds us that morality is not about isolation but about the deep, often invisible ties that bind us together.

Consequences of This Understanding of Morality

If we accept Schopenhauer’s claim that compassion is the foundation of morality, then several important consequences follow. First, morality cannot be limited to humans alone. Since animals can feel pain, their suffering also becomes ethically relevant. Schopenhauer was one of the first Western philosophers to explicitly argue for compassion toward animals, and this view resonates today in debates about animal rights and vegetarianism.

Second, this approach changes how we think about moral obligations. Instead of following laws because they are commanded, we act morally because we are moved by another’s plight. This makes moral life less about rigid rules and more about cultivating sensitivity. Consider everyday examples: choosing to help a struggling neighbor, showing patience with a coworker under stress, or advocating for refugees—all flow from compassion rather than from abstract principles.

Finally, this perspective has a transformative effect on social ethics. If compassion is truly central, then violence, cruelty, and indifference are not just moral failings but a denial of our shared humanity. This is why Schopenhauer’s teaching aligns with traditions like Buddhism, which emphasize empathy as the path to overcoming suffering. In today’s globalized world, where crises cross borders, his message pushes us to expand our circle of concern and to treat the suffering of distant others as morally urgent.

Critical Reflections on Schopenhauer’s View

While Schopenhauer’s focus on compassion is both inspiring and revolutionary, it also invites important questions. Can compassion really serve as the sole and reliable basis of morality? Critics argue that emotions, while powerful, can also be unstable. For instance, we may feel compassion more strongly toward people who are close to us or who resemble us, but fail to extend the same care to distant strangers. This partiality could make compassion an uneven guide for moral decision-making.

Another challenge is that compassion can be manipulated. Political propaganda often uses images of suffering to stir emotions, but not always for just causes. In contrast, rational frameworks like Kant’s ethics or theories of human rights attempt to provide universal standards that apply regardless of our immediate feelings. From this perspective, compassion may need to be combined with reason, rather than replacing it entirely.

However, even these criticisms acknowledge Schopenhauer’s important contribution: he shifted attention from cold logic to the human heart. His philosophy forces us to ask whether morality without compassion would lose its true meaning. This debate remains alive in contemporary ethics, where many argue for a balance between emotional empathy and rational principles of justice.

The Relevance of Schopenhauer’s Idea Today

Although Schopenhauer lived in the 19th century, his claim that compassion is the basis of morality continues to resonate in the 21st. In a world facing humanitarian crises, climate change, and systemic inequality, his message feels strikingly current. Global problems require more than technical solutions; they demand a shift in moral perspective. Compassion encourages us to recognize the suffering of people far beyond our immediate circle—whether refugees crossing borders, victims of war, or even future generations affected by environmental damage.

Modern psychology and neuroscience also reinforce his insight. Studies show that empathy promotes prosocial behavior, while societies that lack compassion often experience division and violence. Even in everyday life, we see how compassion strengthens communities: volunteering during natural disasters, supporting colleagues under stress, or advocating for marginalized groups.

Philosophically, Schopenhauer’s idea challenges us to reconsider what makes morality meaningful. If ethics is grounded only in laws or social contracts, it risks becoming mechanical. But when compassion is central, morality becomes personal, human, and deeply connected to lived experience. This is why Schopenhauer’s thought continues to inspire both academic philosophy and practical movements for justice and peace.

You might be interested in…

- The Limits of Vision in Schopenhauer’s Philosophy – What He Meant by ‘Every man takes the limits of his own field of vision for the limits of the world’

- “Compassion Is the Basis of Morality” – Schopenhauer’s Radical View on Ethics

- “The World Is My Representation” – Understanding Schopenhauer’s Radical View of Reality

- “Man Can Do What He Wills but He Cannot Will What He Wills” – Schopenhauer’s Challenge to Free Will

- “The Person Who Writes for Fools Is Always Sure of a Large Audience” – Schopenhauer’s Sharp Critique of Mass Culture