Quote Analysis

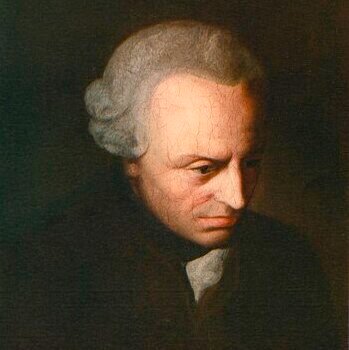

When Immanuel Kant declared:

“Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law,”

he wasn’t merely proposing a moral guideline—he was laying the philosophical groundwork for modern deontological ethics. This statement, known as the categorical imperative, challenges us to evaluate every action by imagining it as a universal principle. But how do we interpret such an abstract idea in practical, everyday life? And what makes this quote so enduring in discussions on morality and duty? In this article, we’ll explore what Kant truly meant, why it matters, and how it still influences ethical reasoning today.

Meaning of the Quote: What Is Kant Actually Saying?

Kant’s quote — “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law” — can sound abstract at first, especially if you’re not used to philosophical language. But let’s break it down together.

A maxim is essentially a personal principle or rule that guides your action. Every time you decide to do something, consciously or not, you are acting according to some internal rule — a maxim. For example: “I will lie to get out of trouble” is a maxim, just like “I will always tell the truth, no matter the cost.”

Now, what does Kant want us to do with these maxims? He says: imagine if everyone acted according to the same rule you are about to follow. Would that be acceptable? Could society function if that rule became universal?

Here’s a simple way to think about it:

- Would the world work if everyone did this?

- Could I rationally want everyone to follow this rule all the time?

- Would I be okay if this rule were applied to me, regardless of the situation?

Kant is asking us to perform a kind of mental test: don’t just think about what you want to do, but think about whether it would be good if everyone acted the same way. If the answer is no — if the maxim fails when universalized — then it’s not morally acceptable.

In short, Kant is challenging us to rise above selfish impulses and evaluate our actions from the standpoint of reason and fairness. He’s saying: if your moral rule isn’t good enough for everyone, then it’s not good enough at all.

The Categorical Imperative as the Foundation of Kant’s Ethics

Kant believed that morality should not depend on personal desires, emotional reactions, or expected outcomes. Instead, he argued that morality must be universal, necessary, and grounded in reason. This belief led him to develop what he called the categorical imperative.

So what is a categorical imperative?

Let’s contrast two types of principles:

- A hypothetical imperative is conditional: “If you want X, then do Y.” For example, “If you want to pass the exam, you should study.” This kind of reasoning depends on your goals and desires.

- A categorical imperative, on the other hand, is unconditional. It says: “You must do Y — period.” No matter what you want, no matter how you feel, you are morally obligated to follow it because it is rational and universal.

Kant’s quote represents the first formulation of the categorical imperative. It tells us that an action is morally right only if the maxim behind it can be applied universally — to all rational beings, in all situations.

This is a radically egalitarian and objective view of ethics. It means:

- Everyone is held to the same moral standards.

- No one gets special exceptions — not even you.

- Your own desires, goals, or emotions don’t excuse immoral actions.

For Kant, morality isn’t about personal benefit or fear of punishment. It’s about respecting the moral law within, and acting out of a sense of duty. Duty here doesn’t mean blind obedience, but rather the free and rational choice to do what is right simply because it is right.

Universality as the Criterion of Morality

One of Kant’s most important contributions to moral philosophy is the idea that morality must be universal. What does this mean in practical terms? It means that a moral principle is valid only if it can apply to everyone, in every situation, at all times — without contradiction.

To help us understand this, Kant invites us to perform what we might call the “universalization test.” Whenever you’re thinking about doing something, ask yourself:

- What is the maxim behind my action?

- Can I imagine a world where everyone follows this same maxim?

- Would that world still function reasonably and justly?

Let’s go through an example. Suppose you consider lying to avoid embarrassment. Your maxim might be: “Whenever telling the truth is inconvenient, I will lie.” Now ask: what would happen if this became a universal law? If everyone lied whenever it was convenient, then trust would completely break down. Promises would become meaningless. In short, lying would no longer work, because the concept of truth would lose its value.

Kant would say that this maxim fails the universality test, and therefore, lying in this way is morally wrong — not because of its consequences, but because it contradicts the logic of universal law.

Here are some signs that a maxim cannot be universalized:

- It involves a contradiction (e.g., promising with no intent to keep the promise).

- It depends on others not doing the same thing (e.g., cheating only works if most people are honest).

- It treats other people as tools, not as equals (which Kant would call “means to an end”).

In summary, the universality test helps us step outside our personal situation and ask: Would I want to live in a world governed by this rule? If the answer is no, then the action is not morally justified.

Free Will and Autonomy as Conditions of Moral Action

Kant firmly believed that freedom is not just a political idea — it is the foundation of moral responsibility. Without free will, there can be no morality, because you cannot be held accountable for actions you were forced to do. But for Kant, freedom means more than just doing whatever you want. It means acting autonomously — guided by your own rational understanding of moral duty.

Let’s break that down.

To act autonomously means to govern yourself. But not in a chaotic or selfish way. Rather, autonomy means:

- You recognize moral laws through reason.

- You choose to follow those laws not because of outside pressure, but because you see them as right.

- You take full responsibility for your choices, because they come from your inner moral compass.

Now contrast this with heteronomy, which means being ruled by something outside yourself — like emotions, social expectations, or personal gain. For Kant, actions based on heteronomy are not truly moral, even if they produce good outcomes. Why? Because you’re not acting from duty; you’re acting from desire or fear.

Here’s an analogy: Imagine two people who donate to charity. One does it because they feel social pressure and want praise. The other does it because they believe helping others is a moral duty, regardless of recognition. According to Kant, only the second person is acting morally, because their action stems from autonomy and moral principle.

Kant’s view can be summed up in this powerful idea:

To be truly free is to be morally self-governing.

You are most human — and most dignified — when you act not as a slave to impulses or outside forces, but as a rational being who chooses to do what is right, simply because it is right.

This connection between freedom and morality also explains why Kant places such importance on respecting the freedom of others. If you treat others merely as a means to an end, you are denying their autonomy — and that, too, is morally wrong.

Why Consequences Are Not the Standard of Morality

One of the most striking aspects of Kant’s moral theory is that he completely rejects the idea that consequences determine whether an action is right or wrong. This stands in sharp contrast to other ethical systems like utilitarianism, where the morality of an action is judged solely by the outcome — whether it increases happiness, pleasure, or utility.

Kant argues that consequences are unpredictable and outside our control. You might do something with the best intentions, and things still go wrong. Or, you might do something selfish, and by chance, it leads to a good result. Does that make the selfish act moral? According to Kant, absolutely not.

Here’s what matters for Kant:

- The principle (maxim) behind your action

- The motive of duty with which you act

- Whether your action respects the moral law

Let’s take an example. Suppose someone tells the truth in a difficult situation, even though it leads to negative consequences (like losing a job or upsetting someone). According to Kant, the action is still morally right because the person acted from duty, with honesty as a universal moral principle — not for personal gain.

By contrast, if someone lies to protect themselves or benefit others, even if it brings good results, it’s still morally wrong. That’s because the maxim behind the action cannot be universalized — and it violates the principle of treating others with respect and dignity.

In simple terms, Kant believes a good will is the only thing that is good without qualification. A moral act must come from a good will, not from fear of punishment, hope for reward, or the desire to create a certain outcome.

Practical Examples of the Categorical Imperative

To make Kant’s philosophy more understandable, let’s look at how the categorical imperative can be applied to everyday situations. We’ll use the universalization test to see whether certain actions can be morally justified.

Here are a few common examples:

- Lying to avoid trouble

Maxim: “I will lie whenever the truth might get me in trouble.”

Universalization: If everyone lied in such situations, trust would collapse, and communication would become meaningless.

Moral verdict: Not permissible. - Breaking a promise for convenience

Maxim: “I will break promises when it suits me.”

Universalization: If everyone did this, promises would lose all value — no one could rely on anyone else.

Moral verdict: Not permissible. - Helping others in need

Maxim: “I will help others when I am able.”

Universalization: A world where everyone helps when they can is sustainable and desirable.

Moral verdict: Permissible and morally praiseworthy. - Cheating on an exam

Maxim: “I will cheat if I know I won’t get caught.”

Universalization: If everyone cheated, grades would become meaningless, and the system would collapse.

Moral verdict: Not permissible.

Kant’s test gives us a clear method for moral reasoning. Instead of asking, “What do I want?” or “What will happen?”, you ask, “Would this be right if everyone did it?” If the answer is no, then you should not do it — no matter how tempting or beneficial the action might seem.

This method helps people develop moral discipline and consistency in their actions, which Kant believed was essential to living with integrity and respect.

The Relevance and Legacy of Kant’s Ethics Today

Though Kant lived in the 18th century, his moral philosophy is still deeply relevant in today’s world — especially in debates about justice, rights, responsibility, and professional ethics.

Let’s look at why his ideas continue to matter:

- Human rights frameworks are often based on Kantian principles. The idea that every person has inherent dignity and must be treated as an end — never merely as a means — is central to modern human rights declarations.

- Professional ethics in fields like medicine, law, and engineering often reflect Kant’s thinking. For instance, doctors must respect patient autonomy, even when outcomes are uncertain. Lawyers are expected to uphold principles, not just win cases at any cost.

- Social justice movements rely on the idea of universal moral principles — that certain rights and wrongs apply to all people equally, regardless of culture, power, or circumstance.

- Environmental ethics can also benefit from Kantian thinking. For example, if we adopt the maxim “Use natural resources responsibly,” we can ask: what if all nations acted this way? Would the Earth remain sustainable?

Moreover, in a world often driven by profit, popularity, or short-term results, Kant’s philosophy challenges us to think more deeply and act more responsibly. He reminds us that being moral is not about being liked or successful — it’s about doing what is right, even when it’s hard.

In conclusion, Kant’s categorical imperative offers more than a rulebook — it offers a vision of a world where people act from reason, respect, and principle. And in a time when ethical clarity is often lacking, that vision is more important than ever.

You might be interested in…

- What Kant Meant by ‘Self-Imposed Immaturity’ – A Deep Dive Into the Spirit of Enlightenment”

- “Happiness Is Not an Ideal of Reason but of Imagination” – Kant’s Radical View on Morality and Emotion

- What Kant Really Meant by “Act Only According to That Maxim…” – A Deep Dive into the Categorical Imperative

- “The Starry Heavens Above Me and the Moral Law Within Me” – Kant’s Timeless Meditation on Awe and Human Dignity

- “Science Is Organized Knowledge, Wisdom Is Organized Life” – What Immanuel Kant Taught Us About Living Intelligently