Quote Analysis

When life throws us into uncertainty—be it suffering, joy, failure, or unexpected fortune—we often feel like passive recipients of fate. But what if the true power lies not in what happens to us, but in how we interpret it?

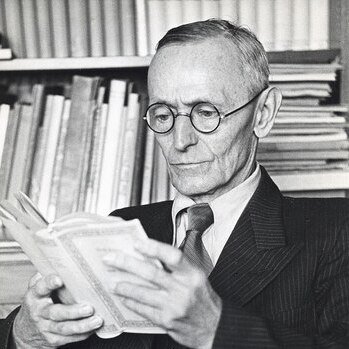

That’s precisely the message Hermann Hesse conveys in Siddhartha (1922), where he writes:

“I have always believed, and I still believe, that whatever good or bad fortune may come our way we can always give it meaning and transform it into something of value.”

This isn’t just poetic idealism. It’s a powerful existential insight that challenges us to reframe adversity and reshape our reality. So, what does Hesse truly mean—and why does this quote still resonate today?

The Meaning of the Quote: Inner Interpretation as Human Power

This quote by Hermann Hesse from Siddhartha emphasizes a fundamental human ability: to give meaning to experience. He tells us that no matter what life brings—joy or sorrow, success or failure—we are not merely victims of fate. Instead, we have the capacity to respond to these events with consciousness and reflection, and in doing so, we can transform them into something valuable.

Let’s break this down:

- “Good or bad fortune” refers to the unpredictable nature of life.

- “We can always give it meaning” highlights the human role as an interpreter, not just a passive observer.

- “Transform it into something of value” shows our ability to extract insight, wisdom, or growth even from suffering.

In other words, meaning is not something we find in life—it’s something we give to life. Hesse is not talking about blind optimism. He is inviting us to be active participants in shaping our experience. Pain doesn’t have to remain just pain—it can become a lesson. Success doesn’t have to be empty—it can be a path to deeper understanding. The quote is a call to reclaim agency over our personal narrative.

Philosophical Foundations: Existential Freedom and the Creation of Meaning

To fully understand Hesse’s message, it helps to look at the philosophical background it resonates with—particularly existentialism. Thinkers like Jean-Paul Sartre, Viktor Frankl, and Søren Kierkegaard all explored the idea that individuals are not defined by external circumstances, but by how they respond to them.

Here are some key points connected to Hesse’s thinking:

- Existential freedom means we are free to choose our attitude, no matter what happens to us.

- Subjective meaning implies that there is no single, universal truth or purpose; instead, each person must find or create their own.

- Responsibility for interpretation suggests that life doesn’t automatically make sense—we are the ones who must give it structure and value.

In Siddhartha, Hesse illustrates this through the protagonist’s journey. Siddhartha rejects second-hand truths, religious systems, and societal definitions of success. He wants to learn from experience, not from doctrine. This mirrors existentialist emphasis on authentic living, where truth is not adopted but discovered through lived reality.

Philosophical Foundations: Existential Freedom and the Creation of Meaning

To fully understand Hesse’s message, it helps to look at the philosophical background it resonates with—particularly existentialism. Thinkers like Jean-Paul Sartre, Viktor Frankl, and Søren Kierkegaard all explored the idea that individuals are not defined by external circumstances, but by how they respond to them.

Here are some key points connected to Hesse’s thinking:

- Existential freedom means we are free to choose our attitude, no matter what happens to us.

- Subjective meaning implies that there is no single, universal truth or purpose; instead, each person must find or create their own.

- Responsibility for interpretation suggests that life doesn’t automatically make sense—we are the ones who must give it structure and value.

In Siddhartha, Hesse illustrates this through the protagonist’s journey. Siddhartha rejects second-hand truths, religious systems, and societal definitions of success. He wants to learn from experience, not from doctrine. This mirrors existentialist emphasis on authentic living, where truth is not adopted but discovered through lived reality.

Spiritual Growth Through Experience, Not Doctrine

One of the most important lessons in Siddhartha is that true wisdom doesn’t come from books, rituals, or teachers—it comes from lived experience. Hesse deliberately presents a protagonist who turns away from established paths, including religious teachings and formal philosophy, in search of something deeper: personal truth.

Siddhartha tries many approaches:

- He follows ascetics and learns self-denial.

- He studies sacred texts and seeks guidance from revered teachers.

- He explores worldly pleasures, wealth, and even fatherhood.

But in each phase, he eventually realizes that these external systems cannot give him the truth he seeks. The turning point comes when he understands that meaning is not something that can be taught—it must be lived. By going through suffering, love, loss, and even silence, Siddhartha learns to hear the voice of life itself.

This is exactly what Hesse is referring to in the quote. It’s not just about enduring good or bad fortune—it’s about transforming each moment into a step on the path to self-realization. And that transformation doesn’t happen in the mind alone; it requires full immersion in the ups and downs of life.

The takeaway here is simple but profound: personal experience is the raw material of inner growth. If we want to become wise, we must not only observe life—we must participate in it, feel it deeply, and then reflect on it honestly.

Acceptance as the First Step Toward Transformation

Hesse’s quote also speaks to a psychological truth that is often overlooked: before we can transform anything, we have to accept it. This means facing reality as it is, without denial or resistance. Whether we are dealing with personal loss, disappointment, or a sudden change in fortune, transformation begins with acknowledgment.

Here’s why acceptance matters:

- It grounds us in reality instead of fantasy or avoidance.

- It gives us a clear starting point for reflection and response.

- It reduces unnecessary emotional suffering caused by resistance.

In Siddhartha, the main character doesn’t begin to truly grow until he stops running—from pain, from pleasure, from confusion. When he sits by the river and listens—not with his ears, but with his entire being—he begins to understand the rhythm of life. That river becomes a symbol of acceptance: it flows without resistance, and yet it contains everything.

Hesse uses this imagery to show that inner peace doesn’t come from controlling events, but from understanding and integrating them. When we accept that joy and sorrow are both part of existence, we become more capable of transforming those experiences into insight, compassion, and resilience.

How to Turn Struggle Into Value in Real Life

While Hesse’s quote sounds poetic and philosophical, njegova snaga se pokazuje tek kada je primenimo u svakodnevnim situacijama. Transforming pain or difficulty into something meaningful is not samo apstraktna ideja – to je praktična veština koju svako može razvijati.

Here are some concrete ways to do that:

- Practice reflection. After a difficult experience, take time to ask: “What did I learn from this?” or “How has this changed me?”

- Express yourself creatively. Art, writing, or even casual journaling can help you turn emotions into insight.

- Use your experience to help others. Sharing your story can give comfort and guidance to people going through something similar.

- Reframe the narrative. Instead of saying “Why did this happen to me?”, try asking “What can I do with this now?”

- Stay present. Even painful moments can become meaningful when you face them consciously, without numbing or avoiding.

In Siddhartha, the main character’s life doesn’t follow a straight path—and that’s the point. The ups and downs are not obstacles to meaning, but the very substance from which meaning is created. In real life, it’s the same. Pain is not inherently noble or useful, but how we respond to it is what gives it value.

So, this part of the quote challenges us to stop asking whether our experiences are “good” or “bad,” and start asking what they could become—if we engage with them fully and honestly.

Man as the Author of His Own Meaning

At the heart of Hesse’s message lies one powerful idea: the human being is not a passive object of fate, but an active creator of meaning. This belief goes against the idea that our lives are shaped only by luck, destiny, or external rules. Instead, Hesse places the responsibility—and the freedom—into our own hands.

This view echoes the existential idea that:

- Meaning is not discovered like a hidden treasure.

- It is constructed through action, thought, and conscious interpretation.

- Each individual is the author of their own story.

Siddhartha does not find meaning by following others. He finds it by walking his own path, even when it’s unclear or painful. And by doing so, he shows us that fulfillment does not come from achieving goals set by society or religion—it comes from deep alignment with one’s inner truth.

This part of the quote is a reminder that your life is not something happening to you. It is something you are shaping, moment by moment, with your awareness, choices, and values. Whether you turn struggle into bitterness or wisdom, joy into ego or gratitude—that is up to you.

In other words, you are not just a character in the story of your life—you are also the narrator. And as Hesse suggests, you always have the power to revise, interpret, and give value to whatever is written on your page.

You might be interested in…

- What Hermann Hesse Meant by “We Can Always Give It Meaning and Transform It into Something of Value”

- “Loneliness Is the Way…” – What Hermann Hesse Really Meant About Solitude and Self-Discovery

- “Some of Us Think Holding On Makes Us Strong” – What Hermann Hesse Really Meant About Letting Go

- “Words Do Not Express Thoughts Very Well” – Hermann Hesse’s Profound Critique of Language and Communication

- “Each Man’s Life Represents a Road Toward Himself” – Unpacking Hermann Hesse’s Philosophy of Self-Discovery