Quote Analysis

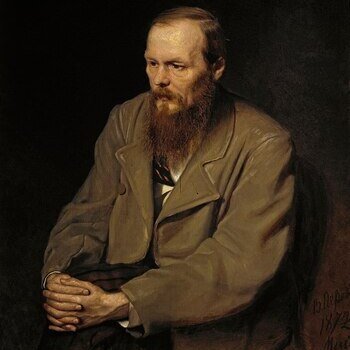

Why would anyone fall in love with suffering? It sounds irrational—yet it speaks to something deeply human. In a world obsessed with avoiding pain and maximizing pleasure, Fyodor Dostoevsky challenges us with a haunting idea:

“Man is sometimes extraordinarily, passionately, in love with suffering…”

These words aren’t just poetic or provocative—they reveal a profound understanding of the human condition. Written in the 19th century, they still echo through literature, psychology, and philosophy today. But what exactly did Dostoevsky mean? And why does this statement still unsettle and enlighten us?

Let’s dive into the meaning behind this powerful quote.

Interpretation of the Quote: Why Would a Person Love Suffering?

This quote by Dostoevsky may sound paradoxical at first. How can someone truly love suffering? But if we look deeper, we find that Dostoevsky is not speaking about everyday preferences—he is touching on the hidden layers of human psychology. The key word here is sometimes. He is not claiming that all people always love suffering, but that under certain conditions, some individuals are drawn to it with intensity, even passion.

Why might this happen?

- Some individuals carry a deep sense of guilt and feel that they deserve to suffer. For them, pain becomes a kind of moral repayment.

- Others see suffering as a path to redemption, a necessary passage to become purified or forgiven.

- There are people who experience emotional emptiness or numbness, and they seek out pain not because they enjoy it, but because it makes them feel something—a proof that they are still alive.

Dostoevsky is not romanticizing pain. He is showing us that in the complexity of the human soul, suffering can sometimes serve a strange, even twisted purpose. It gives meaning, awakens the conscience, or offers a sense of identity when everything else feels hollow.

Dostoevsky and the Psychology of the Human Soul

Long before psychology became a formal science, Dostoevsky was exploring the dark corners of the human psyche with remarkable precision. His characters are not symbols or caricatures—they are psychological case studies. They reflect real inner conflicts, including the irrational pull toward self-destruction.

In this quote, we see one of Dostoevsky’s most powerful insights: humans are not strictly logical or self-preserving. Sometimes, they choose what harms them. Why?

- Because they want to prove their freedom—not just to others, but to themselves.

- Because they believe that suffering brings them closer to truth or justice.

- Because avoiding pain at all costs feels, in some cases, like moral cowardice.

This is especially visible in characters like Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment, who is tormented by guilt after committing murder. His suffering is not a punishment imposed from the outside, but a storm rising from within. He needs to suffer—because only through that agony can he begin to rebuild himself.

Dostoevsky anticipates what psychoanalysis would later call the death drive or the compulsion toward self-sabotage. But he adds a moral and spiritual layer that modern psychology often overlooks: suffering is not just a symptom—it can be a form of inner truth.

Suffering as a Path to Moral Transformation

In Dostoevsky’s worldview, suffering is not meaningless. On the contrary, it plays a crucial role in human growth, particularly moral and spiritual development. This idea is deeply rooted in Christian thought, especially in Eastern Orthodox theology, where pain is often seen not merely as a burden, but as a trial that purifies and reveals.

For Dostoevsky:

- Suffering awakens conscience. It forces a person to confront who they really are.

- It humbles pride. Through pain, people often see their limits and become more compassionate.

- It breaks the illusion of control and reminds the person of their vulnerability—and their need for grace or forgiveness.

In his novels, characters often reach moral clarity only after going through periods of intense pain. It’s not an easy path, but it’s one that leads to self-knowledge, humility, and sometimes even love. For Dostoevsky, suffering can tear a person down—but it can also rebuild them on a more honest foundation.

This does not mean that suffering is good in itself. Rather, Dostoevsky is saying that it can be used for good, if the person chooses to face it with honesty and openness. It becomes a moment of moral transformation—not because it’s pleasant, but because it breaks the shell of illusion and forces the soul to grow.

Freedom and Irrationality: Why Humans Sometimes Choose What Hurts Them

In many philosophical systems, especially in rationalist traditions, human beings are seen as creatures who naturally seek what benefits them—pleasure, security, happiness. But Dostoevsky challenges this idea. He insists that we are not only driven by logic or comfort. In fact, sometimes people deliberately choose what is harmful, painful, or destructive. Why? Because they want to prove they are free.

This is a central theme in Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground, where the narrator rejects the idea that human behavior can be predicted like a mathematical formula. He argues that even if reason tells us what is best, we might still do the opposite—just to assert our autonomy.

There are several key ideas here:

- Choosing pain can feel like an act of rebellion against a world that tries to control us.

- Irrational choices give a person a sense of inner authority—they are not just machines reacting to external incentives.

- Sometimes, people harm themselves simply because the ability to do so proves that no one—not society, not science, not even God—can fully own their will.

Dostoevsky’s point is not that people should act irrationally, but that they can. And that this capacity is part of what makes us human. To be free, in his view, includes the possibility of choosing wrongly—and even tragically.

Suffering and Meaning: An Existentialist Insight

Dostoevsky’s thinking here anticipates the ideas of later existentialist philosophers like Søren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, and even Viktor Frankl. For all of them, suffering is not something to be avoided at all costs—it can be the moment when a person comes closest to discovering who they really are.

Let’s be clear: not all suffering is meaningful. There is senseless violence, pointless cruelty, and emotional pain that breaks people rather than builds them. But Dostoevsky is interested in a specific kind of suffering—the kind that forces a person to confront their deepest values, beliefs, and illusions.

This kind of suffering:

- Strips away the distractions of everyday life.

- Makes a person ask fundamental questions: Who am I? What do I believe in? What is worth living—or dying—for?

- Can lead to the discovery of purpose, especially if the individual endures it with integrity and reflection.

This is what Viktor Frankl would later call the search for meaning in suffering. In Dostoevsky’s world, characters who suffer authentically often come out transformed—not always happier, but more aware, more grounded, more human.

The pain does not provide the answer, but it clears the ground on which real answers can finally be sought.

Suffering as a Mirror of Human Nature

What makes Dostoevsky’s quote so powerful—and unsettling—is that it doesn’t offer an easy moral lesson. He’s not telling us to chase suffering, nor is he suggesting that pain is noble by itself. What he is saying is something more complex: that suffering reveals truths about us we often try to hide.

It exposes:

- the limits of rational thinking,

- the strange paradoxes of human freedom,

- the deep hunger for meaning that comfort alone cannot satisfy.

In a time when many people are taught to avoid discomfort at all costs, Dostoevsky reminds us that some truths only come through hardship. Not because suffering is good—but because it is honest. It strips us down. And when everything else is gone, what remains may finally be real.

This is why the quote—“Man is sometimes extraordinarily, passionately, in love with suffering…”—still speaks to us today. It challenges us to reflect not just on pain itself, but on what we become through it.

You might be interested in…

- Why “Pain and Suffering Are Always Inevitable for a Large Intelligence and a Deep Heart” Still Resonates Today

- Why “The Mystery of Human Existence Lies Not in Just Staying Alive” Is Dostoevsky’s Deepest Insight About Meaning

- Why ‘To Go Wrong in One’s Own Way Is Better Than to Go Right in Someone Else’s’ Captures Dostoevsky’s Philosophy of Freedom

- Why “Man is Sometimes Extraordinarily, Passionately, in Love with Suffering” Still Resonates – Dostoevsky’s Psychological Depth

- What Dostoevsky Meant by “Nothing is easier than to denounce the evildoer; nothing is more difficult than to understand him”