Quote Analysis

Not every great mind lives in peace—and not every deep heart escapes sorrow. Fyodor Dostoevsky, the Russian literary giant, once wrote:

“Pain and suffering are always inevitable for a large intelligence and a deep heart.”

This haunting reflection isn’t just poetic; it captures a profound psychological and philosophical reality. Why is it that those who feel more deeply and think more clearly also seem to carry heavier emotional burdens? In this post, we’ll explore the deeper meaning behind Dostoevsky’s quote, examine how it reflects his worldview, and understand why it still speaks to our modern condition—perhaps now more than ever.

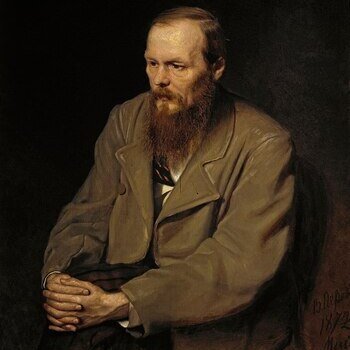

Introduction to the Thought of Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky wasn’t just a novelist—he was a thinker, a soul explorer, and someone who dared to write about the deepest corners of human experience. In his works, you won’t find simple answers or cheerful optimism. Instead, you’ll encounter raw truth, moral conflict, and emotional depth that can shake the reader to their core.

The quote “Pain and suffering are always inevitable for a large intelligence and a deep heart” reveals one of Dostoevsky’s central beliefs: that those who see the world more clearly and feel it more deeply are often the ones who suffer the most. But why is that?

To understand the quote, we need to understand the man behind it. Dostoevsky’s life was marked by intense suffering—prison, illness, poverty, existential doubt. He didn’t write from a distance. He wrote from experience. His worldview was shaped by questions of guilt, grace, and the mysterious nature of the human soul.

This idea is not meant to be depressing for its own sake. Instead, it’s a philosophical observation: the more we become aware of life’s complexity, injustice, and fragility, the harder it is to remain untouched. In that sense, Dostoevsky connects suffering with depth—not as punishment, but as a consequence of perception.

What Does It Really Mean: “Pain and Suffering Are Always Inevitable for a Large Intelligence and a Deep Heart”?

Let’s break this quote into parts like we’re analyzing a complex sentence in a literature class.

- “Pain and suffering”: These aren’t just physical hurts or short-term discomforts. Dostoevsky is talking about existential pain—the kind that comes from awareness, empathy, and reflection. This kind of suffering runs deep and lasts long.

- “Are always inevitable”: He doesn’t say sometimes or often. He says always. That’s a strong claim. It means there is no way around it. Once someone reaches a certain level of insight or emotional openness, they will suffer. It’s not a matter of if, but when and how deeply.

- “For a large intelligence and a deep heart”: These two traits go hand in hand in Dostoevsky’s thought. A “large intelligence” means the capacity to see beyond appearances—to understand systems, motives, hypocrisies, and hidden truths. A “deep heart” means the ability to care, to empathize, to feel the weight of others’ suffering as if it were your own.

Put together, the quote suggests the following idea:

The smarter and more emotionally attuned you are, the more you realize how broken, unfair, and fragile the world is. You start noticing things others miss—loneliness in a smile, injustice in a law, tragedy in a routine. And that knowledge hurts.

This doesn’t mean we should avoid developing intelligence or empathy. Quite the opposite—Dostoevsky believed that suffering, when faced honestly, can lead to spiritual depth, humility, and wisdom. But we must be prepared: emotional and intellectual depth often comes with a price.

In simpler terms, imagine a child who sees the world as perfect—and an adult who knows it’s not. Who suffers more? The one who understands more. Dostoevsky invites us not to fear this suffering, but to use it—to grow through it, not run from it.

Awareness of the World as a Source of Pain

One of the central reasons Dostoevsky links suffering with great intelligence and deep emotion is that awareness—true, unfiltered awareness—is often painful. The more clearly you see the world for what it is, the harder it is to stay indifferent or unbothered.

Let’s break it down simply. When someone begins to notice:

- the gap between what people say and what they actually do

- the injustice that is built into systems, not just individual actions

- the fragility of life and how quickly things can fall apart

- the loneliness hidden behind polite conversations

- the helplessness of good people in the face of cruelty or absurdity

…they can’t just “unknow” those things. A sensitive mind can’t pretend not to see, and a compassionate heart can’t ignore what it feels.

This awareness creates what we might call existential tension. You live in the same world as others, but you don’t experience it the same way. Where others see routine, you might see tragedy. Where others find comfort in easy answers, you are burdened by difficult questions. That kind of inner life isn’t always visible on the outside, but it’s exhausting to carry.

Dostoevsky understood that this kind of suffering isn’t dramatic—it’s quiet, internal, and constant. It’s the cost of living with open eyes and an open heart.

Dostoevsky’s Characters as Embodiments of This Idea

If we want to truly understand what Dostoevsky meant by this quote, we should look at how he expressed it—not just in words, but in the lives of his characters. His novels are not essays. They are emotional laboratories, where big ideas are tested through human experience.

Two of his most well-known characters perfectly embody this connection between depth and suffering:

- Rodion Raskolnikov (Crime and Punishment)

Raskolnikov is intellectually brilliant. He creates a theory that justifies murder for a supposed greater good. But once he acts on that idea, his conscience and his sensitivity won’t let him rest. His inner torment isn’t just about guilt—it’s about the collapse of a worldview. He suffers because he understands, too late, the complexity of morality and the weight of human life. - Prince Myshkin (The Idiot)

Myshkin is the opposite of Raskolnikov in temperament. He is kind, innocent, emotionally intuitive. But in a world full of manipulation, cruelty, and social games, his goodness becomes a weakness. People don’t know what to do with someone who refuses to play by their rules. He ends up isolated and broken—not because he lacks intelligence, but because he has too much heart.

What do these characters teach us? They show that suffering is not a flaw in the system—it’s a natural result of being awake, aware, and emotionally present in a world that often punishes those very traits.

In Dostoevsky’s universe, the more “human” you are in the deepest sense—capable of both understanding and compassion—the more you are likely to suffer. But that suffering is not meaningless. It’s what shapes the soul, reveals truth, and—sometimes—leads to redemption.

Suffering as a Path to Inner Transformation

Dostoevsky doesn’t glorify suffering in a superficial or romantic way. He never says that pain is good just because it hurts. What he suggests is something deeper: suffering, when faced with honesty and courage, can lead to personal transformation.

Think of suffering not as a dead-end, but as a door—one that forces us to confront things we usually ignore, such as:

- our moral limitations

- our need for control

- our illusions about the world and ourselves

- the fragile nature of happiness

In Dostoevsky’s novels, characters who suffer deeply often go through some kind of spiritual awakening. They don’t come out of it unchanged—they come out more humble, more real, sometimes even more loving.

For example, in Crime and Punishment, Raskolnikov’s journey through guilt and psychological torment breaks down his intellectual arrogance and brings him to a more human place. He doesn’t simply “get better”; he becomes someone new.

This is a key part of Dostoevsky’s worldview: pain is not the goal, but it’s often the price of truth. Without facing it, we risk living shallow lives, disconnected from deeper meaning. So instead of avoiding suffering at all costs, Dostoevsky suggests we let it teach us.

Why This Quote Still Speaks to Us Today

You might ask: this was written in the 19th century—why should we care now? The answer is simple: because the human condition hasn’t changed that much. If anything, modern life has made Dostoevsky’s insight even more relevant.

Today, we live in a world full of information, noise, and emotional overload. People with “large intelligence” are bombarded by global problems, contradictions, and ethical dilemmas. People with “deep hearts” are overwhelmed by stories of suffering, injustice, and division.

And yet, we are constantly told to be “happy,” to “stay positive,” to “move on.” This creates a strange pressure to avoid or suppress pain, as if it were a sign of weakness. But Dostoevsky reminds us: pain is not a failure—it’s often a reflection of awareness and humanity.

This quote gives voice to people who feel too much, think too much, and wonder if something is wrong with them. It tells them: no, there’s nothing wrong. You are simply awake in a world that prefers sleep.

That’s why this quote still resonates. It offers a kind of quiet validation, a recognition that you’re not alone in your struggle—and that your pain might, in fact, be a measure of your depth.

Similar Ideas in Philosophy and Literature

Dostoevsky was not the only one to explore the connection between deep thought, emotional sensitivity, and suffering. Many other philosophers and writers, across different cultures and eras, have expressed similar insights.

Here are a few examples worth considering:

- Friedrich Nietzsche: He famously wrote, “He who has a why to live can bear almost any how.” Nietzsche believed that suffering could be meaningful if it led to growth or insight.

- Søren Kierkegaard: As a Christian existentialist, Kierkegaard explored the idea that anxiety and despair are signs of spiritual awareness, not mental failure. He believed that the deeper the person, the greater the inner conflict.

- Franz Kafka: His characters often live in absurd, painful worlds where logic breaks down. For Kafka, suffering reveals the alienation of the modern soul.

- Albert Camus: Camus didn’t deny the pain of existence—he embraced it as part of the absurd condition. Yet, he still believed in personal integrity and courage in the face of suffering.

- Simone Weil: A lesser-known but profound thinker, Weil saw attention to others’ suffering as a moral act. She argued that only those who have suffered can truly understand and love.

These thinkers may differ in their beliefs, but they share one core idea: that suffering is closely tied to human depth. Not everyone will suffer in the same way—but those who think and feel deeply will never escape it entirely. And perhaps they shouldn’t.

Is Suffering Truly Unavoidable for the Sensitive and the Wise?

So, where does that leave us? Should we simply accept that if we are intelligent or compassionate, we are doomed to suffer?

Not necessarily. What Dostoevsky offers is not fatalism, but realism. He tells us: suffering will come—but it’s what you do with it that matters.

You have two main choices:

- You can resist it, deny it, or numb yourself to it—which often leads to bitterness, cynicism, or emotional shutdown.

- Or, you can face it, learn from it, and allow it to deepen your understanding of yourself and others.

That’s not easy. But it’s meaningful. And in Dostoevsky’s view, meaning is more valuable than comfort.

In the end, this quote isn’t just a warning—it’s a kind of invitation. An invitation to live honestly, even when it hurts. An invitation to grow through the very pain you’d rather avoid. And most of all, an invitation to accept that being human—fully, deeply human—comes with a cost.

But it also comes with beauty.

You might be interested in…

- Why “Man is Sometimes Extraordinarily, Passionately, in Love with Suffering” Still Resonates – Dostoevsky’s Psychological Depth

- Why ‘To Go Wrong in One’s Own Way Is Better Than to Go Right in Someone Else’s’ Captures Dostoevsky’s Philosophy of Freedom

- Why “The Mystery of Human Existence Lies Not in Just Staying Alive” Is Dostoevsky’s Deepest Insight About Meaning

- What Dostoevsky Meant by “Nothing is easier than to denounce the evildoer; nothing is more difficult than to understand him”

- Why “Pain and Suffering Are Always Inevitable for a Large Intelligence and a Deep Heart” Still Resonates Today