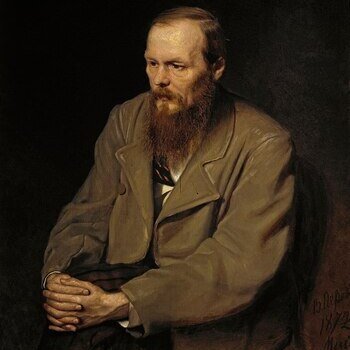

Quote Analysis

When Fyodor Dostoevsky wrote:

“The mystery of human existence lies not in just staying alive, but in finding something to live for,”

he wasn’t merely making a philosophical statement—he was capturing the essence of what it means to be human. In a world obsessed with survival, productivity, and routine, his words strike at the heart of our existential condition. Why do we wake up every morning? What drives us beyond the biological imperative to survive? Dostoevsky’s insight reminds us that true life begins only when we discover a reason to live. Let’s explore what he really meant.

Meaning of the Quote

At first glance, this quote by Dostoevsky may seem like a poetic reflection, but in reality, it expresses a profound existential truth. It challenges the idea that simply surviving is enough. According to Dostoevsky, human beings are not satisfied with mere existence—we need purpose, direction, and something greater than ourselves to truly feel alive.

Let’s clarify the two parts of the quote:

- “Staying alive” refers to biological survival—eating, sleeping, breathing, avoiding danger.

- “Finding something to live for” refers to psychological and spiritual fulfillment—a goal, a belief, a love, a mission.

In other words, a human being who has food, shelter, and physical safety but lacks a deeper reason to wake up in the morning is not truly living, at least not in the full human sense. Dostoevsky is pointing to a mystery: despite all our progress and knowledge, we still struggle with one question—why are we here, and what makes life worth living?

This idea separates humans from other species. Animals focus on survival; humans reflect, ask questions, and search for meaning. That need for meaning is not a luxury—it’s essential. When people lack purpose, they experience emptiness, anxiety, and sometimes despair. This is why the quote remains so powerful: it speaks to our need to live with intention, not just inertia.

Philosophical Background – Existentialism and the Search for Meaning

Dostoevsky’s quote fits naturally into the framework of existentialist philosophy. Existentialism explores the nature of human existence, especially in a world where traditional sources of meaning—religion, authority, tradition—are no longer absolute.

The central idea of existentialism is that life does not come with built-in meaning. Instead, each individual must find or create their own reason to live. That might sound simple, but it’s actually a heavy responsibility. It means that:

- No one else can define your purpose for you.

- You are free to choose your path—but also responsible for your choices.

- Without purpose, freedom can feel like a burden, not a gift.

This connects closely with philosophers such as Søren Kierkegaard, who emphasized the individual’s “leap of faith” toward meaning, or Viktor Frankl, who survived the Holocaust and later wrote Man’s Search for Meaning. Frankl argued that the will to meaning is a core human drive. People can endure almost anything—poverty, suffering, even imprisonment—if they have a why.

Dostoevsky anticipated much of this thought. He didn’t call himself an existentialist, but his novels wrestle with the same questions: What happens when people lose meaning? What do we do when we no longer believe in traditional values? His characters often live on the edge of despair, searching for something—anything—that gives them a reason to go on.

Psychological Dimension – Why Humans Need a Reason to Live

From a psychological point of view, Dostoevsky’s quote reflects a fundamental truth: humans are not mentally or emotionally built to survive on routine and necessity alone. We are meaning-seeking creatures. Without something to strive for, our emotional health begins to break down.

Let’s look at why this is the case.

When people feel their lives lack purpose, they often experience:

- A sense of emptiness or numbness

- Loss of motivation and energy

- Increased anxiety or depression

- Disconnection from others and the world

- A tendency toward addictive or self-destructive behaviors

Simply put, when we don’t know why we’re doing something, it becomes harder to do it with joy or commitment. Imagine waking up every day with no goal beyond just going through the motions—this quickly leads to emotional fatigue.

Psychologist Viktor Frankl, a Holocaust survivor, emphasized this insight in his theory called logotherapy. He argued that the search for meaning is not just a philosophical activity but a psychological necessity. According to Frankl, people can survive extreme suffering—as long as they believe it serves a purpose. But without that belief, even comfort can feel unbearable.

That’s why Dostoevsky’s quote is so important: it warns us not to neglect our inner world. A person with food, shelter, and safety may still suffer deeply if they feel their life has no value. And the opposite is also true—a person facing hardship can still feel whole and resilient if they have something worth living for.

In everyday life, this “reason to live” can take many forms:

- A deep relationship

- A creative or professional mission

- A sense of service or contribution

- A spiritual or religious belief

- A commitment to growth or truth

None of these need to be dramatic or grand. What matters is that they give you a sense of direction—something to lean on when life gets difficult.

Suffering as a Path to Meaning – Dostoevsky’s View on Pain and Purpose

Dostoevsky believed that suffering is not always something to be avoided. In fact, in many of his works, suffering is a central path through which characters grow, mature, or find redemption. This idea may seem hard to accept at first—why should pain be necessary? But Dostoevsky wasn’t glorifying suffering for its own sake. Rather, he saw it as a potential gateway to self-understanding and deeper meaning.

In his novels, characters often go through personal crises, guilt, loss, or inner torment. And through those trials, they sometimes discover:

- A deeper sense of compassion

- A more honest view of themselves

- A spiritual or moral awakening

- A clearer understanding of what really matters

Let’s take Crime and Punishment as an example. The protagonist, Raskolnikov, suffers greatly—not just because of external punishment, but because of the psychological and moral weight of his crime. His path to redemption doesn’t come through comfort, but through confrontation with his own pain and guilt.

Dostoevsky is saying something crucial here: meaning is not always found in happiness—it is often born out of struggle. Unlike superficial forms of pleasure, which can fade quickly, meaning gained through suffering tends to be lasting and transformative.

This doesn’t mean we should seek out pain, but rather that when it comes, we shouldn’t waste it. Pain can either destroy us or shape us, depending on how we respond to it. When we find a reason within the suffering—whether it’s love, faith, or self-respect—it stops being meaningless.

In modern terms, this message remains powerful. Many people today are told to avoid discomfort at all costs. But Dostoevsky invites us to consider another approach: not to romanticize pain, but to respect its role in helping us grow.

Spiritual and Religious Dimension – Faith as a Source of Meaning

In Dostoevsky’s view, faith plays a crucial role in helping individuals find something worth living for. But it’s important to understand that he didn’t present faith as blind obedience or religious ritual. Rather, he saw it as a personal, inner relationship with something higher—something that gives human life dignity, direction, and hope, especially in times of suffering or moral crisis.

For Dostoevsky, faith was a deeply existential matter. It wasn’t about escaping the world, but about facing it with a different kind of strength—one rooted in spiritual conviction. In characters like Father Zosima or Alyosha from The Brothers Karamazov, faith is portrayed as a calm, humble force that allows people to endure hardship without falling into despair or cynicism.

Here are a few ways Dostoevsky connects faith to the search for meaning:

- Faith gives people the courage to suffer without losing hope.

- It provides a moral compass when external rules break down.

- It allows for forgiveness—of oneself and others—which is essential for healing.

- It connects the individual to something eternal, beyond temporary worldly struggles.

Dostoevsky was not naïve about faith. He recognized that doubt, confusion, and inner conflict are part of spiritual life. But he believed that in a world full of pain and injustice, faith can be a lifeline—a way for the human soul to hold on to meaning when reason alone falls short.

This perspective challenges modern secular views that see religion as outdated or irrelevant. Dostoevsky is not preaching; he is inviting us to consider that, for many people, spirituality is not about rules but about reasons. Reasons to love, to forgive, to endure, and ultimately, to live.

Contemporary Relevance – Why This Quote Still Matters Today

Although Dostoevsky wrote these words in the 19th century, their message is perhaps more relevant today than ever. We live in a time of material abundance but emotional and existential scarcity. Many people have everything they need to survive—food, shelter, comfort—yet still feel empty, anxious, or lost. The question “What am I living for?” remains as urgent now as it was in Dostoevsky’s time.

There are several modern factors that make this quote especially timely:

- The rise of consumerism has led many to seek happiness in possessions or status, but these rarely provide lasting meaning.

- Social media encourages comparison, performance, and distraction, which often deepen feelings of purposelessness.

- Traditional belief systems have weakened, leaving a vacuum many struggle to fill.

- Mental health challenges—such as depression and burnout—are increasingly linked to a lack of perceived meaning in life.

Dostoevsky’s insight challenges us to stop and reflect. Are we just existing, or are we truly living? Are we chasing short-term rewards, or are we connected to something deeper—something that gives our life coherence and purpose?

In a world full of noise, speed, and superficial goals, this quote reminds us that the real task is inner work. Finding meaning doesn’t always require big achievements or dramatic transformations. Often, it begins with asking honest questions and listening to what matters most to us.

Whether that meaning comes from relationships, creativity, justice, faith, or service, Dostoevsky’s wisdom is clear: without it, we may survive—but we will never truly live.

You might be interested in…

- Why “Man is Sometimes Extraordinarily, Passionately, in Love with Suffering” Still Resonates – Dostoevsky’s Psychological Depth

- Why “The Mystery of Human Existence Lies Not in Just Staying Alive” Is Dostoevsky’s Deepest Insight About Meaning

- Why “Pain and Suffering Are Always Inevitable for a Large Intelligence and a Deep Heart” Still Resonates Today

- What Dostoevsky Meant by “Nothing is easier than to denounce the evildoer; nothing is more difficult than to understand him”

- Why ‘To Go Wrong in One’s Own Way Is Better Than to Go Right in Someone Else’s’ Captures Dostoevsky’s Philosophy of Freedom