Quote Analysis

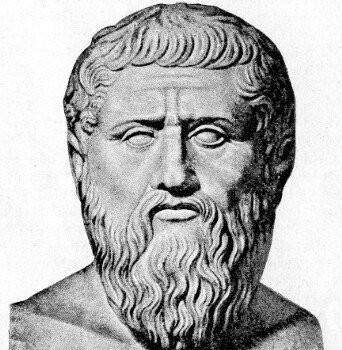

Love doesn’t just happen to people, Plato suggests—it activates them. It changes how you pay attention, what you desire, and how much effort you’re willing to invest in becoming better. In Symposium, Plato explores Eros as a force that pulls the mind upward, turning ordinary life into something more intentional and alive. That’s why a single line can feel so surprisingly modern:

“At the touch of him every one becomes a poet…”

But what does it actually mean to “become a poet” here—and why does Plato treat love as a source of creation rather than mere emotion?

What the Quote Means at First Glance

Plato’s line sounds simple: once Love “touches” a person, that person becomes a poet. But if you read it like a teacher would explain it, the key is to understand what “poet” means here. Plato is not handing out a compliment to professional writers. He is describing a change in the inner state of a human being. In this context, a “poet” is someone who can shape experience into meaning—someone who can take feelings, ideas, and desires and turn them into something formed, deliberate, and expressive.

The word “touch” is also not literal. It is a metaphor for that moment when something becomes personally significant. Before the “touch,” you may live mechanically: you work, scroll, talk, sleep, repeat. After the “touch,” your attention sharpens. You start noticing details. You care more. You become capable of effort that previously felt impossible.

A clear modern example: a person can be average at their job until they fall in love with a craft—design, cooking, music, coding, teaching. Suddenly they practice longer, learn faster, and pay attention to small things. That shift is what Plato calls becoming a “poet”: not a maker of rhymes, but a maker of form and meaning.

The Symposium Context: Eros as a Force That Moves You

In Symposium, the conversation is not about sweet romance. It is a philosophical investigation into Eros—love as desire, drive, and upward movement. Plato treats Eros like an engine inside the human mind: it pulls you from what you have toward what you lack, and from what is ordinary toward what feels higher and more valuable. This is why love in Plato is rarely calm. It is active. It pushes. It educates you through longing.

Think of Eros as a kind of inner tension: you sense beauty, goodness, or excellence, and you want to get closer to it. That desire can start with something physical or personal, but Plato’s point is that it can develop into something more refined. You move from liking a beautiful face to appreciating a beautiful character, then to loving wisdom, then to loving what is truly good. In Plato’s picture, Eros is a ladder that trains your soul to aim higher.

This explains why “everyone becomes a poet.” When Eros is present, people stop being passive. They become builders of something: a relationship, a skill, a life direction, a better version of themselves.

You can see the same mechanism today. People often change the most when they have a strong “why.” They don’t just want comfort—they want meaning. Plato is describing that psychological shift, but in philosophical language.

Not Just Romance: The Psychology of Meaning and Focus

Here is the practical lesson: Plato is talking about how deep importance creates energy. When something matters to you at the core—whether it’s a person, a mission, or a value—your mind reorganizes itself around that goal. You become more focused, more disciplined, and more imaginative, because your attention is no longer scattered.

This is why the quote feels so accurate even now. Motivation is not only about willpower; it is often about value. If you don’t care, everything feels heavy. If you care deeply, effort becomes lighter because it has a direction. Plato is describing what we could call today “meaning-driven performance.”

To make it concrete, notice how people behave when they genuinely love something:

- They learn faster because curiosity keeps pulling them forward.

- They tolerate frustration better because the goal feels worth it.

- They notice details because attention is emotionally anchored.

- They become creative because they want to express what they feel.

This is why an artist works differently when they feel they must say something, not just when they want applause. It’s why someone becomes braver when they love a person or a cause: fear doesn’t vanish, but meaning becomes stronger than fear.

Plato frames this as the “touch” of Eros. In modern terms, it is the moment when your inner life becomes organized by purpose—and that is exactly when creativity becomes realistic, not mystical.

How Love Turns an Ordinary Person into a Creator

Plato’s biggest idea here is that love does not simply decorate life with emotion. It creates movement—and movement produces creation. Once you are moved, you begin shaping reality: through words, actions, habits, and choices. That is why he uses the image of poetry. Poetry is structured expression. And love, in Plato’s view, gives your life structure.

Importantly, creation here is not limited to art. You can “become a poet” in many everyday ways:

- You become a poet in relationships when you stop reacting and start building trust with patience and care.

- You become a poet in work when you stop doing tasks and start crafting quality.

- You become a poet in self-improvement when you stop “trying to be better” vaguely and start practicing specific virtues.

Plato connects Eros with elevation. The love that matters most is the love that makes you ask: “How should I live, if I truly value this?” That question alone changes behavior. It turns a person from drifting to choosing.

A modern example is someone who begins to take responsibility after becoming a parent. Their life becomes more deliberate: time is planned, priorities sharpen, patience grows. Another example is someone who falls in love with a discipline—fitness, writing, philosophy—and gradually becomes the kind of person who can carry that discipline. They don’t just consume; they produce.

Eros as Uplift: From Attraction to Virtue

Plato’s key move in Symposium is to treat love as something that can educate desire. You do not start by loving “the good” in an abstract way. Most people begin with what is close and visible: a person, a face, a voice, a talent, a moment of charm. Plato is not shocked by that—he expects it. The lesson is what happens next. If Eros is healthy and guided, it does not trap you at the first level. It becomes a force that lifts you from surface attraction to deeper admiration, and finally to virtue.

Historically, this idea matters because Greek philosophy often aimed at shaping character. Plato is not giving dating advice; he is describing moral development. Love becomes a ladder: first you are pulled by beauty, then you learn to recognize what makes beauty worth trusting—such as self-control, honesty, courage, fairness.

A modern example is simple. Someone might be drawn to a partner because of charisma, but over time they either learn to value reliability and kindness—or the relationship collapses. Or think of a young athlete who starts training for status, but then learns to respect discipline itself. The original attraction is not the final destination. In Plato’s frame, love becomes mature when it pushes you toward being worthy of what you admire. That is why Eros “pulls upward”: it invites a better version of you.

Why “Poet” Also Means Builder, Teacher, and Self-Repairer

When Plato says love makes “everyone” a poet, he is teaching a broad idea: creation is not limited to art. A poet, in this sense, is someone who can bring order and meaning into life. You “compose” your actions like lines in a poem: with intention, rhythm, and purpose. This is why the quote applies to ordinary people, not only to artists.

To make it concrete, think about the kinds of creation that are easy to miss:

- Building a relationship: not through intense feelings, but through small repeated choices—honest conversations, repaired mistakes, shared routines.

- Building a skill: practicing a craft until your work has form—clear writing, clean code, better cooking, stronger teaching.

- Building character: training patience, resisting impulses, keeping promises. That is “self-repair,” and it is a real creative act.

- Building a community: being the person who sets the tone—calm, fair, consistent—so others become better around you.

In Plato’s time, education was seen as shaping the soul. Love, then, becomes a kind of inner teacher. It pushes you to form yourself, not only to feel something. Modern language would call this “identity-based effort”: you act differently because you now see yourself as responsible for something meaningful. That is why love makes life productive, not just emotional.

How to Recognize the “Touch of Eros” in Real Life

People often imagine “inspiration” as lightning: dramatic, rare, and unpredictable. Plato’s point is more practical. The “touch” of Eros is the moment when something becomes non-negotiably important to you—important enough to reorganize your attention and behavior. It can be romantic, but it can also be love for truth, learning, craftsmanship, or a person you want to protect.

You can recognize this touch by observing specific signs:

- You voluntarily return to the same thing again and again, even when nobody forces you.

- Your standards rise. You start noticing what is sloppy, shallow, or dishonest—first in the world, then in yourself.

- You become more patient with difficulty because the goal feels worth the cost.

- You begin to plan. Not obsessively, but seriously—time, priorities, routines.

A modern example: someone who discovers a vocation (medicine, design, writing, engineering) often changes their lifestyle. They stop wasting time because they feel a pull. Another example: a person who falls in love with a child (as a parent or mentor) becomes more responsible. They may still feel tired, but the tiredness gains meaning, and meaning makes effort sustainable.

So, in teacher-like terms: the “touch” is not magic. It is the birth of commitment. And commitment is the bridge between desire and creation.

When Eros Elevates vs. When It Traps: The Difference Between Love and Obsession

Plato’s view can be misunderstood if we treat all strong desire as “love.” He would likely warn you: Eros can uplift, but it can also enslave. The difference is not intensity; the difference is the direction of your life after the desire appears.

Uplifting Eros makes you larger. Trapping Eros makes you smaller.

Here is a clear comparison you can teach and remember:

- Uplifting Eros increases clarity: you become calmer, more honest, more consistent.

- Trapping Eros increases chaos: you become reactive, jealous, compulsive, easily destabilized.

- Uplifting Eros respects the other person or the value you love; it does not try to possess it.

- Trapping Eros turns the object of desire into a drug: you need it to regulate your mood.

In modern psychology terms, obsession often looks like emotional dependence. You don’t want to become better; you want relief. Plato would say that is not the Eros that makes you a poet. The “poet-making” Eros produces form—stable habits, better speech, better choices. Obsession produces noise—endless rumination, dramatic highs and lows, loss of self-control.

This matters because many people confuse pain with depth. Plato teaches the opposite: genuine love tends to create order, not destruction.

The Core Lesson: Why This Quote Still Matters Today

Plato’s sentence survives because it describes a pattern that people keep rediscovering: what you love shapes what you become. It is not simply that love feels good; it is that love changes your attention, and attention changes your life. In a world full of distraction, this idea becomes even more relevant. Many people do not lack talent—they lack a stable center.

Plato gives a direct answer: Eros can become that center, if it is aimed well. When your desire points toward something genuinely valuable—beauty understood as excellence, goodness, truth—your life gains direction. That direction produces creativity, not only in art but in decisions, relationships, and self-development.

A modern example is the difference between “motivation hacks” and real devotion. Hacks produce short bursts. Devotion produces long-term change. Plato is describing devotion: the kind that turns practice into identity. That is why he can say “everyone becomes a poet.” The claim is not that everyone becomes talented. The claim is that everyone becomes form-giving—capable of shaping a life with meaning—once love becomes a guiding force rather than a passing mood.

You might be interested in…

- Why Plato’s “Until philosophers are kings…” Still Matters: Power, Wisdom, and Leadership

- The Meaning of “Justice Was Doing One’s Own Business” — Plato’s Warning Against Being a “Busybody”

- The Meaning Behind “Is Not Philosophy the Practice of Death?” — Plato’s Lesson on Inner Freedom

- Why Plato’s “Education is the art which will effect conversion…” Still Matters Today – Learning as a Change of Direction

- The Meaning Behind “At the Touch of Him Every One Becomes a Poet…” — Plato’s Idea of Love as a Creative Force