Quote Analysis

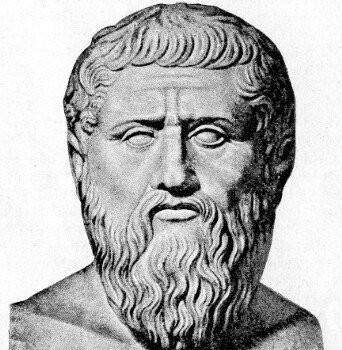

When politics becomes a contest of popularity, money, or fear, a society can end up ruled by the loudest voices rather than the wisest minds. That tension is exactly what Plato targeted in The Republic, where he argued that stability and justice require something rare: leadership guided by disciplined thinking and moral character. In that spirit, he famously wrote:

“Until philosophers are kings, or philosophers are kings…”.

The line sounds radical, but Plato’s point is practical—power without wisdom drifts into crisis, while wisdom without power changes nothing. So what was he really demanding from rulers?

What Plato Means by “Until philosophers are kings…”

Plato is not praising people who can talk cleverly or quote books. In The Republic, a “philosopher” is someone trained to think clearly, test ideas, and resist self-deception—especially when emotions and crowds push in the opposite direction. So when he says “Until philosophers are kings, or philosophers are kings…”, he is saying: a society won’t be well-governed until the people who hold power are also the people most committed to truth, self-control, and the common good.

A helpful way to understand the point is to contrast two kinds of leaders. One leader decides based on what gets applause today. Another leader decides based on what will still make sense in ten years, even if it is unpopular now. Plato thinks the first type is naturally pulled toward crises, because public mood changes fast and rewards quick wins. The second type can handle complexity and delay gratification.

In modern terms, Plato is demanding that leadership include:

- The ability to learn and revise beliefs when evidence changes.

- The character to resist temptation—money, ego, revenge, status.

- The discipline to prioritize long-term outcomes over short-term image.

That is why his line is not a romantic slogan. It is a hard standard.

Plato’s Deeper Critique of Politics: Not Just Corruption, but the Wrong Drivers

Plato’s complaint about politics goes deeper than “some officials steal.” He thinks a state becomes unstable when leadership is driven by the wrong inner forces. Even an honest leader can still be a bad leader if they are ruled by fear, vanity, or the need to be loved. In Plato’s view, those motivations distort judgment the way a crooked ruler distorts measurement: you think you’re being “practical,” but you are quietly bending reality.

He worries about three common drivers:

- Fear-driven rule: Leaders react to threats (real or imagined) and start governing through suspicion. This can produce harsh policies, scapegoats, and endless emergency thinking.

- Desire-driven rule: Leaders chase wealth, comfort, or influence. Institutions become tools for private gain, and public trust collapses.

- Popularity-driven rule: Leaders chase applause. Decisions become performances, and truth becomes whatever sells best.

Historically, Plato had reasons to be skeptical. Athens experienced turbulent shifts in leadership, and he watched how public mood could elevate confident speakers even when their decisions were reckless. A modern parallel is policy that is designed mainly to “win the week” rather than solve the problem—like treating a chronic illness with only painkillers because they work fast and look good, while the underlying cause grows worse.

Appearance vs Truth: Why Plato Thinks Education Matters for Governing

One of Plato’s most practical ideas is that people often confuse what looks convincing with what is actually true. A persuasive speech, a simple slogan, or a confident face can feel like knowledge—but it may be only a well-packaged guess. That is why Plato connects good rule with serious education: not education as a diploma, but education as mental training.

To govern well, a leader must handle situations where the “obvious” answer is wrong. For example, a policy might make everyone feel safer today but create bigger risks later. Or a popular economic move might boost short-term numbers while damaging long-term stability. Plato believes that without trained judgment, leaders get trapped by the surface.

He would say a strong ruler must learn to:

- Separate emotion from evidence without becoming cold or cruel.

- Ask “What is the real cause?” instead of “What will people like?”

- Notice hidden trade-offs: every choice solves one problem but can create another.

A clear modern example is social media politics. A short, emotional message spreads faster than a careful explanation, so leaders are tempted to govern in headlines. Plato’s warning is simple: if leaders live inside appearances, the state will be ruled by illusion—because illusion is always easier to sell than reality.

Why Plato Tries to Combine Power and Wisdom (and Why It’s So Rare)

Plato’s bold move is to demand a union that usually falls apart: power (the ability to enforce decisions) and wisdom (the ability to decide well). He thinks either one alone is dangerous or useless.

Power without wisdom is like giving a fast car to someone who cannot drive: you get speed, but also accidents. A leader may be energetic, charismatic, and decisive—yet still steer society into avoidable disasters because they lack depth, patience, or moral discipline. Wisdom without power is like knowing the right medicine but having no access to the patient: insight stays private and the public situation does not change.

Plato also understands why the combination is rare. Power attracts people who crave status, control, and recognition. Wisdom requires the opposite habits: humility before truth, willingness to be corrected, and resistance to ego. In other words, the qualities that make someone seek power are often the same qualities that make them misuse it.

That is why Plato’s “philosopher-king” is not a celebrity-intellectual. It is a person trained to govern themselves first. The deeper lesson is still modern: the best leaders are not simply smart—they are steadily principled, able to think long-term, and strong enough to resist the intoxication of authority.

A Modern Translation: The Three Qualities Plato Would Demand From Leaders Today

If we translate Plato’s idea into a clear, modern checklist, we do not need crowns or ancient titles. We need leaders with specific habits of mind and character. Plato’s point is that good leadership is not mainly a matter of charm or ideology—it is a matter of disciplined judgment and self-control under pressure.

Here are three qualities that capture his demand in practical terms:

- The ability to learn and change course when facts require it. A serious leader treats new evidence like a map update, not like an insult. For example, if an economic plan fails, the mature response is not to blame enemies forever, but to adjust policies and admit what was misjudged. Plato would call this respect for truth over ego.

- A character strong enough to resist the temptations of power. Power offers easy rewards: special favors, loyal followers, flattery, and immunity. Plato insists that a leader must be trained to resist these, the way a surgeon is trained to resist panic during a difficult operation.

- Long-term responsibility instead of short-term marketing. Many political decisions are designed to win the next week, not the next decade. Plato wants leaders who can delay applause and still act for future stability—like investing in infrastructure or education even when it is not instantly “popular.”

This is not idealism. It is leadership hygiene: without these qualities, power becomes dangerous.

The Weak Spot in Plato’s Idea: Who Decides Who Is a “True Philosopher”?

Plato’s proposal sounds strong, but it carries a serious risk: if you say “only the wise should rule,” someone must decide who counts as wise. And that decision can be abused. This is the main reason many readers become cautious when they hear “philosopher-king.”

There are three classic problems:

- Elitism: A small group can claim, “We know what is best,” and treat disagreement as ignorance. That is dangerous because it can silence valid criticism. Even intelligent people can be wrong, and power makes it harder to notice mistakes.

- Self-selection: If the “wise” choose the next “wise,” you can get a closed club. Over time, it stops being about truth and becomes about loyalty. Historically, many regimes have justified control by claiming superior knowledge.

- Fake wisdom: A person can look thoughtful—calm voice, clever language, impressive credentials—while still being driven by ambition. Plato’s ideal requires deep integrity, but integrity is harder to measure than intelligence.

So the teacher-like lesson here is simple: Plato gives a useful standard (wisdom + character), but the system needs safeguards. Without transparency and accountability, the label “philosopher” can become a mask for domination rather than a guarantee of good judgment.

How to Recognize “Philosophical” Leadership in Real Life

Plato is not asking us to search for perfect people. He is asking us to recognize patterns of thinking that usually lead to better decisions. “Philosophical” leadership is visible in behavior, not in self-presentation.

Look for practical signs like these:

- They explain reasons, not only conclusions. When a leader says “We are doing X,” they also show the logic and trade-offs behind it. This invites evaluation instead of demanding blind trust.

- They tolerate correction and reward honest feedback. A leader who punishes disagreement creates an echo chamber. Plato would say that an echo chamber is the enemy of truth, because it replaces reality with comfort.

- They separate popularity from correctness. Sometimes the right decision is unpopular at first—like reducing wasteful spending or regulating harmful industries. A philosophical leader can hold that line without turning cruel or arrogant.

- They can hold complexity without panicking. Real problems are rarely solved by one slogan. A philosophical leader can say: “This will take time, and here is the plan,” rather than selling miracles.

A modern example might be crisis management. In a public health emergency, a leader who respects evidence, communicates uncertainty honestly, and adjusts policy as data improves is practicing exactly the disciplined thinking Plato associates with genuine wisdom.

Why the Quote Still Matters Today: Attention Economy, Short-Term Incentives, and Permanent Crisis

Plato’s warning feels modern because we live in a system that rewards speed, emotion, and spectacle. In such a climate, leaders are pressured to perform rather than to govern. Social media, constant polling, and 24/7 commentary create a political environment where the “appearance of strength” can matter more than actual competence.

Plato would say this produces a dangerous cycle:

- Short-term incentives push leaders toward short-term decisions. If success is measured by headlines, leaders choose what looks good now, even if it harms stability later.

- Emotional politics crowds out careful reasoning. Fear and anger are powerful tools. They mobilize people quickly, but they also make populations easier to manipulate.

- Complex problems get simplified into tribes and slogans. Once politics becomes identity warfare, truth becomes secondary. People defend their side first and evaluate facts second.

Historically, Plato saw how democracies can slide into instability when public mood becomes the main guide. Modern societies face a similar risk when information is fragmented and outrage spreads faster than reflection.

So the lasting lesson is not “philosophers should literally rule.” The lesson is: a society must design leadership standards and institutions that reward truth-seeking, self-control, and long-term responsibility—otherwise politics becomes a factory of crises.

You might be interested in…

- The Meaning Behind “Is Not Philosophy the Practice of Death?” — Plato’s Lesson on Inner Freedom

- Why Plato’s “Until philosophers are kings…” Still Matters: Power, Wisdom, and Leadership

- The Meaning Behind “At the Touch of Him Every One Becomes a Poet…” — Plato’s Idea of Love as a Creative Force

- Why Plato’s “Education is the art which will effect conversion…” Still Matters Today – Learning as a Change of Direction

- The Meaning of “Justice Was Doing One’s Own Business” — Plato’s Warning Against Being a “Busybody”