Quote Analysis

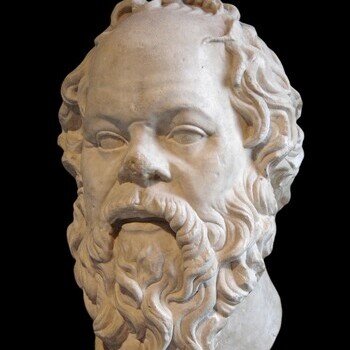

Most people believe they’re fair—until they’re hurt, betrayed, or humiliated. That’s when the mind starts negotiating: “I had a reason.” Socrates refuses that negotiation. His blunt claim:

“So one must never do wrong.”

It sounds almost too simple, yet it targets the most common excuse behind revenge and “justified” harm. The point isn’t whether anger makes you feel entitled to strike back; it’s whether your character survives the moment intact. If you answer injustice with injustice, you may win the conflict—but you risk becoming what you despise. So what did Socrates really mean, and why is it still so demanding today?

What “Never Do Wrong” Really Means in Socrates’ Ethics

When Socrates says we must never do wrong, he is not giving a polite motivational slogan. He is stating a rule that does not change with mood, pressure, or circumstance. In his moral thinking, “wrong” is not defined by whether you get caught, whether society approves, or whether the outcome benefits you. Wrong is what damages justice and integrity—what makes you act against what you know is fair.

A helpful way to understand him is to separate results from principles. Many people judge actions by success (“It worked, so it was fine”). Socrates judges actions by whether they keep the soul—meaning character—clean. For him, doing wrong is like poisoning yourself to make someone else suffer.

Think of common situations:

- You spread a rumor because someone spread one about you.

- You cheat “a little” because “everyone does it.”

- You lie to protect your image, not to protect someone’s safety.

Socrates would say the moment you choose the unjust option, you are training yourself to become comfortable with injustice. That is why his “never” is so strict: it protects your moral compass from sliding little by little.

The “I Had a Reason” Excuse and Why Socrates Rejects It

A reason can explain behavior, but it cannot automatically justify it. This is the lesson Socrates is pushing. People often confuse these two things. They say, “I lied because I was scared,” or “I was harsh because I was hurt.” Those statements may be psychologically true, but Socrates would answer: being scared explains the lie; it does not make lying right.

He is teaching moral clarity: your emotions do not rewrite what counts as right or wrong. If anger could turn injustice into justice, then morality would become a weather report—different every day.

Modern life gives easy examples. Imagine a colleague takes credit for your work. You feel wronged. Now you are tempted to “balance the scales” by sabotaging them, embarrassing them publicly, or bending rules against them. Socrates would call that a trap: you are using their wrongdoing as permission to corrupt your own standards.

He would also warn you about the quiet version of this excuse—“It’s just a small thing.” Small wrongs are dangerous because they feel harmless, but they create a habit of self-approval. Once your mind learns to say “I had a reason,” it will find reasons more quickly next time. Socrates is protecting you from becoming your own best lawyer.

Revenge as a Moral Trap: Why Injustice Cannot Cure Injustice

Socrates connects this principle strongly to revenge. Revenge feels like justice because it promises emotional relief: “Now they’ll understand.” But Socrates insists that revenge is not justice if it repeats the wrong. It is simply a second wrong wearing the costume of fairness.

Here is the key teaching: you can defend yourself without becoming unjust. That means you can set boundaries, seek accountability, and stop harm—without using cruelty, deception, or humiliation.

Consider the difference:

- You report fraud to protect others (justice).

- You forge evidence to destroy the person (revenge).

- You end a toxic relationship and leave (boundary).

- You ruin their reputation with lies (wrongdoing).

Socrates wants you to see that revenge often changes the avenger more than it changes the target. If you answer injustice with injustice, you slowly become someone who believes wrong is acceptable—when it feels satisfying. That is exactly how moral decline happens: not through one dramatic decision, but through repeated “just this once” moments.

This is why his rule is so “uncomfortable.” It blocks the easiest emotional solution and forces the harder one: act firmly, but cleanly. Do what is necessary, but do not poison your character in the process.

Winning vs. Being Right: Why Integrity Matters More Than “Victory”

Socrates is teaching a distinction many people ignore: you can win and still be wrong. In everyday life, “winning” often means getting the promotion, proving someone wrong, getting the last word, or making the other person pay. But Socrates asks a sharper question: What did you become while you were winning?

If you win through manipulation, bullying, or dishonesty, you might gain an external result while losing something internal. For Socrates, that internal loss is serious because it shapes the whole person. A person who repeatedly “wins” by unjust methods becomes the kind of person who needs injustice to feel strong.

A modern example is social media conflict. You can “win” an argument by mocking someone, taking their words out of context, or rallying a crowd against them. It may look like victory, but it trains your mind to treat people as targets rather than humans. Socrates would say that kind of victory is self-defeat.

In his view, the highest success is not dominance—it is consistency with what is right. That consistency builds trust, self-respect, and long-term stability. So the quote is not about being naïve or passive. It is about refusing to trade your integrity for a short-term advantage. The hardest part is accepting that real moral strength is often quiet: you walk away from the “easy win” because you refuse to become unjust to obtain it.

Why Doing Wrong Harms You Even If No One Notices

Socrates is not mainly worried about punishment or reputation. His focus is deeper: what wrongdoing does to the person who commits it. In ancient Athens, people often feared public shame, legal penalties, or loss of status. Socrates shifts the spotlight to an inner consequence: wrongdoing reshapes character, even when it stays hidden.

Think of it like training. Every action is a repetition that strengthens a certain “moral muscle.” If you practice fairness, you become more reliably fair. If you practice small dishonesties, you become more comfortable with dishonesty. That comfort is the danger.

A simple modern example: a person exaggerates achievements on a résumé. No one checks. They get the job. It “works.” But something changes:

- They become more willing to distort facts again.

- They start seeing truth as flexible when it helps them.

- They feel a quiet anxiety: “What if someone finds out?”

Even if exposure never happens, the person has trained themselves to prefer advantage over honesty. Socrates would say this is a real loss, because integrity is not a decoration—it is the foundation of stable judgment. When the foundation cracks, future choices become easier to justify in the wrong direction.

Morality Is Not Seasonal: Either the Principle Holds or It Doesn’t

Socrates’ sentence sounds strict because it refuses “exception thinking.” Many people treat morality like a rulebook with loopholes: “I’m honest, but this situation is different.” Socrates argues that once you allow a moral principle to switch on and off, it stops being a principle and becomes a preference.

Historically, this connects to the Greek idea that virtue is a stable disposition, not a costume you wear for public events. If you are just, you are just in private and in public—especially when it is inconvenient. Otherwise, justice is only a performance.

Here is the teacher-like test: If you accept the rule only when it benefits you, you don’t actually accept the rule. You accept comfort.

A modern example is online behavior. Someone claims to value respect and fairness, but when they are criticized, they suddenly excuse cruelty: “They started it,” “They deserve it,” “It’s just the internet.” Socrates would say this is exactly when the principle is being tested. Morality matters most when emotions rise, because that is when people tend to abandon it.

So “never do wrong” is not perfectionism. It is consistency: the same moral standard applies whether you are calm or angry, praised or insulted, winning or losing.

How to Apply the Quote in Everyday Life Without Becoming Passive

A common misunderstanding is that Socrates is teaching weakness: “If you never do wrong, you must accept being mistreated.” That is not the point. Socrates is not saying, “Let people harm you.” He is saying, don’t become unjust while protecting yourself.

In practice, you can respond firmly while staying clean in method. That means choosing actions that stop harm without adding new harm. For example, if someone lies about you at work, you can act:

- Document facts and communicate them clearly.

- Speak to a manager or HR using evidence, not insults.

- Set boundaries: reduce contact, refuse collaboration, request mediation.

- Leave an environment that rewards unfairness.

Notice what is missing: revenge tactics like sabotage, public humiliation, or spreading counter-lies. Those actions may feel satisfying, but they make your moral identity dependent on the other person’s behavior.

This is where the quote becomes practical philosophy. Socrates is teaching that you can be strong without being dirty. Real strength is not “I can hurt you back.” Real strength is “I can protect myself without turning into a person who needs wrongdoing to cope.”

Common Misreadings: Does This Mean You Must Never Break Rules?

Another important clarification: Socrates says “never do wrong,” not “never break a rule.” These are different. Laws and social norms can be imperfect. In Socrates’ time, Athens had laws and customs that were debated, and he himself became a symbol of tension between personal conscience and public authority.

So how do you interpret the quote responsibly today? You must ask: Is the action wrong in a moral sense, or is it merely disobedient? Sometimes breaking a rule can be morally justified if the rule itself is unjust—but even then, Socrates would insist on the manner: not through cruelty, deception for selfish gain, or harm for pleasure.

Consider two scenarios:

- A person lies to steal money. That is wrongdoing.

- A person breaks a minor rule to protect someone from harm. That may be disobedience, but not necessarily wrongdoing—depending on intention and consequences.

Socrates’ core lesson is that moral reasoning must be disciplined. You do not decide based on convenience, ego, or anger. You decide based on what strengthens justice and integrity. The quote demands mature judgment: not blind rule-following, but a steady refusal to corrupt yourself—even when you could “get away with it.”

You might be interested in…

- The Meaning Behind “If it were necessary either to do wrong or to suffer it…” — Why Socrates Chose Suffering Over Injustice

- The Meaning Behind “I neither know nor think that I know” — Socrates on Intellectual Humility

- The Meaning Behind “The Unexamined Life Is Not Worth Living” — What Socrates Really Meant

- What Socrates Meant by “Not Life, but a Good Life, Is to Be Chiefly Valued” — Why Integrity Matters More Than Survival

- Why Socrates Said “So One Must Never Do Wrong” — The Hardest Test of Moral Consistency