Quote Analysis

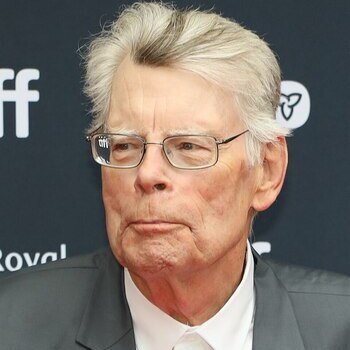

Most people don’t quit because they lack talent—they quit because they keep waiting to feel ready. In a world obsessed with motivation, Stephen King offers a colder, more useful truth: consistency beats mood. His line:

“Amateurs sit and wait for inspiration, the rest of us just get up and go to work,”

Isn’t a romantic view of creativity—it’s a practical philosophy of discipline. But what is King really warning us about when we delay? And why does “waiting for inspiration” so often turn into a polite form of fear? Let’s break down the psychological and philosophical weight behind this quote—and what it changes in the way you build skills.

What the quote really means: the myth of inspiration vs. the power of habit

Stephen King is correcting a common misunderstanding about creative work. Many people treat inspiration like a green light: “When I feel inspired, I will start.” The problem is that inspiration is irregular. It comes and goes, and it is often influenced by mood, sleep, stress, and distractions. If you make inspiration your starting condition, you give control of your progress to factors you cannot manage well.

Habit works differently. A habit is a repeatable action tied to time and place. When you work at a consistent hour, in a consistent setting, your brain learns the pattern. Over time, focus becomes easier to access because the environment itself becomes a cue. This is why professionals can produce steady output: they don’t wait to “feel” ready; they practice being ready.

Historically, this idea is visible in crafts and apprenticeships. A carpenter, a printer, or a classical composer did not rely on emotional waves. They relied on daily practice, repetition, and refinement. The same logic applies today. If you write 300 words every morning, you create more progress in a month than someone who waits for a perfect weekend.

Key points to understand (ordenery list):

- Inspiration is a spark; habit is the engine.

- Routine reduces decision fatigue and lowers resistance.

- Consistent practice produces reliable quality, not occasional brilliance.

The psychology of procrastination: “waiting for inspiration” as a disguised fear

This quote is also a warning about procrastination. People often say they are waiting for inspiration, but the real issue is frequently emotional discomfort. Starting a task exposes you to uncertainty: you might struggle, you might produce something mediocre, or you might have to face criticism. Waiting feels safer because it keeps you in the world of potential, where nothing can be judged yet.

In a teaching context, think of procrastination as an avoidance strategy. The mind tries to protect self-esteem by delaying the moment of evaluation. This is why perfectionism is so closely connected to procrastination. If you believe the first attempt must be impressive, you will hesitate to begin. King’s message is practical: do the work even when you feel unprepared. The first draft, first version, or first attempt is not a final verdict—it is raw material.

Modern examples are everywhere. A person learning programming might delay building projects because they fear “not being good enough.” A designer might scroll for inspiration endlessly because they fear making the wrong choice. A writer might keep researching instead of writing because research feels productive without the risk of failure. The solution is action with low pressure: start small and keep moving.

What to focus on (ordenery list):

- Procrastination often hides fear of failure or judgment.

- Perfectionism raises the “starting cost” so high that you avoid starting.

- Small, concrete steps reduce anxiety and make progress measurable.

- Work creates clarity; waiting usually creates more doubt.

The philosophical dimension: work ethic and respect for your own talent

King’s quote has an ethical message. He is not saying that talent is irrelevant; he is saying talent deserves discipline. In philosophy, this connects to virtue ethics: character is built through repeated actions. If you repeatedly choose to show up and do the work, you are training a trait—reliability, courage, patience. Over time, that trait becomes part of who you are, not just what you “try” to do.

There is also a Stoic element here. Stoicism emphasizes focusing on what is within your control. Inspiration is not fully controllable. Effort is. Time at the desk is. The decision to practice is. King’s “get up and go to work” is essentially a Stoic move: stop negotiating with your mood and start acting on your values.

Historically, many strong creative traditions were built on discipline: daily writing schedules, strict studio routines, structured rehearsal. The romantic image of the artist waiting for a muse is attractive, but it is unreliable. A more mature view is that creativity is a skill strengthened by repetition, like playing an instrument. You don’t wait for the perfect feeling to practice scales—you practice so the skill is available when it matters.

Core theses to develop (ordenery list):

- Discipline is a form of self-respect: you invest time in what you claim matters.

- Professionalism is behavior, not a label—consistency is the proof.

- Values become real through action; intentions alone do not build character.

- The ethical choice is to work with what you have today, not with excuses.

Professionalism as behavior: what separates “amateurs” from people who deliver

In King’s sentence, “amateur” is not simply someone who is new. It describes a work style: a person who depends on mood, ideal conditions, and external validation. A professional, in contrast, builds reliability. Reliability means that output appears even on average days, not only on exceptional days. This is the key difference teachers want you to understand: in real life, results are judged by consistency, not by your intentions.

Historically, professionalism developed in crafts and trades. A printer, a tailor, or a surgeon could not afford to wait for the “right feeling.” Their work affected customers, patients, and deadlines. That practical tradition later influenced modern creative industries. Writers, journalists, and screenwriters learned to treat creativity like a job: you show up, you produce drafts, you revise. The first version may be imperfect, but the process is dependable.

A modern example is content creation or software development. If you only work when you feel inspired, projects stall. If you work on a schedule, even in small pieces, the project moves forward. Notice the principle: professionals reduce drama. They don’t make every session a test of identity (“Am I talented today?”). They treat each session as one step in a longer process.

What professionalism looks like (ordenery list):

- You start at a planned time, not at a perfect mood.

- You measure progress by effort and output, not by excitement.

- You accept imperfect drafts as necessary stages.

- You keep promises to yourself the same way you keep promises to others.

Modern application: how skills are actually built in writing, design, programming, and learning

King’s idea becomes very clear when you look at skill-building. Skills grow through repeated exposure to problems, feedback, and correction. Waiting for inspiration skips the most important part: the boring middle where you practice fundamentals. In education, we call this deliberate practice. It is not glamorous, but it is effective.

Take writing. Improvement comes from producing many pages, then editing, then learning why certain sentences work. If you write only when inspiration appears, you produce too little material to improve. Take design. Good design requires seeing many layouts, trying solutions, and training your eye through iteration. If you keep searching for the perfect reference, you delay the hands-on work that teaches you composition and hierarchy. Take programming. You learn by building, breaking, debugging, and refactoring. That cycle is the classroom. The moment you start a small project, you meet real problems—and real learning begins.

A useful teaching analogy is sports training. You do not become strong by waiting for a day when lifting feels effortless. You become strong by showing up, doing manageable sets, and repeating them over weeks. Creative and intellectual skills follow the same logic.

Practical ways to apply this (ordenery list):

- Choose a daily minimum (for example, 30 minutes or one small task).

- Separate “production” from “evaluation” (create first, judge later).

- Track input and output (time spent, pages written, problems solved).

- Use small deadlines to create momentum (today’s task must be finishable).

Practical conclusion: inspiration follows motion, and routine protects your progress

A clear lesson from King is that inspiration is often an effect, not a cause. When you begin working, your mind gathers cues: words on the page, a shape on the canvas, a bug in the code, a question you cannot answer yet. Those cues generate ideas. This is why people frequently feel “inspired” after they have already started. Motion creates material, and material creates direction.

Routine also protects your progress from life’s unpredictability. If your system depends on perfect conditions, it collapses when you are tired, busy, or stressed. If your system depends on simple rules—show up, do the minimum, continue tomorrow—then progress continues even during imperfect weeks. This is not about being harsh; it is about being realistic.

From a philosophical angle, routine is a form of self-governance. You are deciding that your values, not your mood, will guide your behavior. That is a mature kind of freedom: you are not enslaved by the need to “feel like it.” You act because the work matters, and feelings can catch up later.

A simple takeaway to remember (ordenery list):

- Start first; motivation often arrives second.

- Make consistency the goal, not constant inspiration.

- Keep the bar low enough to start, and high enough to grow.

- Treat your craft with respect by giving it regular time and attention.

You might be interested in…

- “Get Busy Living or Get Busy Dying” Meaning Explained — What Stephen King’s Quote Really Demands From You

- The Meaning Behind “Amateurs Sit and Wait for Inspiration” — Stephen King on Discipline and Real Creative Work

- Why Stephen King’s “We Make Up Horrors to Cope With the Real Ones” Explains Our Love of Horror

- Why “The Scariest Moment Is Always Just Before You Start” Hits So Hard — Stephen King on Fear, Action, and Momentum

- The Meaning Behind “Books Are a Uniquely Portable Magic” — Why Stephen King’s Line Still Matters Today